The Voice referendum has been mired in hyper-partisan politics and gladiatorial culture-wars. In media forums, much of the public advocacy has “sunk into a maelstrom” as Senator Pat Dodson puts it. In the final weeks of the campaign, leaders on both sides have called for “more respectful debate”.

What would this look like? For months, experts and media commentators have done lots to inform the substance of the Voice idea and how referendums work. But less to promote “respectful debate” as a process of public engagement and deliberation, to inform voter decisions.

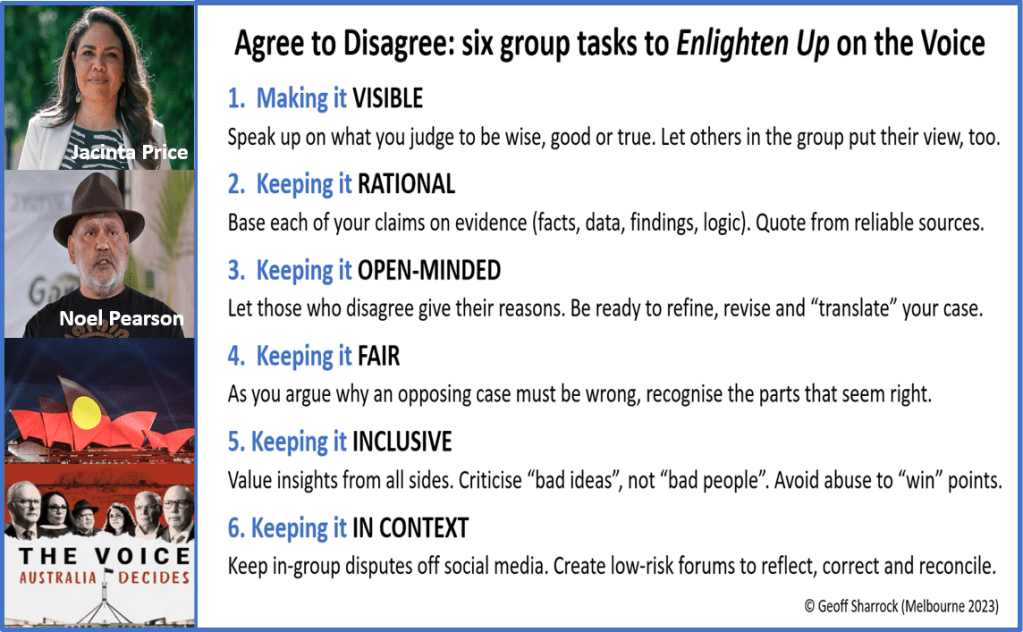

My checklist for “enlightening” debate on university campuses at Chart 1 offers six ways to widen the space for dialogue across perspectives. Here participants share views, identify areas of conflict, clarify issues and options, and revise or reaffirm standpoints.

1. The first task (make it visible) presumes that it’s OK to disagree. For this, two-way tolerance is key. If only one side speaks, “invisible” concerns are left undiscussed; and any common ground – behind the opposing views on specifics – also becomes less visible.

In Voice debates both the Yes and No camps want to get Indigenous communities out of entrenched disadvantage. Consider two prominent voices, Jacinta Price and Noel Pearson. Both reject “passive welfare” models. Both endorse “real” economic participation. Both are critical of “wasteful” government spending.

But despite this common ground, they are at odds on how best to fix these problems at the system level.

Pearson also wants to revitalise traditional cultures – what he has called Indigenous Australians’ “internalisation of the Enlightenment”. Price may well also support this “enlightenment” element of Pearson’s “radical centre” vision – in principle. But she has other priorities: auditing how funds are spent on Indigenous programs and organisations; and targeting government inaction on the abusive and violent elements she sees within some cultures. Her rejection of “romanticised” narratives that ignore or downplay this puts her own activism (as a member of Parliament) at odds with the Yes camp vision that Pearson personifies.

2. A second task (keep it rational) is to confirm the relevant facts and the logic of the Yes and No cases. Here confusion and misinformation loom large. (Media reporting that highlights the “outrage” factor with clickbait images, quotes and headlines doesn’t help).

For example, many Australians think governments spend $30-$40 billion a year on Indigenous programs. But as fact-checkers note, this isn’t quite right.

In fact, reliable, up-to-date figures have been surprisingly absent from the main statements on offer from both the Yes and No camps. As far as I know, close to $40 billion is spent now, in total across all levels of government. In 2019 the Cape York Institute estimated total (State and Commonwealth) spending on Indigenous citizens at $35 billion a year. But 15-20% of this is on Indigenous-specific programs. In 2016 it was 18% of $33 billion, in Productivity Commission reporting. The rest is spent on programs that all Australians rely on, such as health care. The Productivity Commission puts total average spending per Indigenous person at about twice the non-Indigenous Australian average. This reflects greater use of all services and higher remote delivery costs. And yes, wasteful spending under patterns of “top-down” and often ineffectual policymaking.

As Constitutional law scholar (one of the Voice architects) Shireen Morris puts it (drawing on a Productivity Commission review of the 2020 National Agreement on Closing the Gap programs): Australia is failing to improve practical outcomes in Indigenous communities. It is why more than $30 billion annually in expenditure is yielding poor results. The report emphasises that practical change requires true partnership with local and regional Indigenous communities. It requires government bureaucracies to work with, and listen to, communities. This doesn’t happen.

Citing examples such as a damaging decision to lift alcohol bans in Alice Springs, Morris presents the Voice as a suitable antidote: “not a veto, just a fairer say”. As with the Closing the Gap programs overseen by the National Indigenous Australians Agency (located in the Prime Minister’s department), the Voice aims to co-ordinate advice to the government from local Indigenous representative bodies on priorities, programs and outcomes. But it would only recommend solutions, not fund or deliver programs by way of NIAA-style partnerships (or like ATSIC, an earlier representative body abolished in 2005). Otherwise, the Yes camp must consider the NIAA (as an internal government agency), as less visible and less independent than the Voice would be.

3. A third task (keep it open-minded) is to understand the “best reasoning” behind both cases. Here “translation” problems loom when key claims are reduced to catchphrases; or when a key term is used to refer to different contexts in ways that alter its meaning.

Example 1: a No camp claim is that the Voice “puts race in the Constitution”. A Yes camp response to this is: “race (power) is already there”. Parliament still has historical power to make “race-based” laws for any ethnic group. But this fact doesn’t nullify No voter concerns about “enshrining unequal civic rights” – in this case for Indigenous groups only, not policymakers via a Parliamentary process. Unlike the 1967 referendum call to “equalise” rights and conditions (by ensuring Indigenous voting rights as citizens, and by enabling the Commonwealth to legislate national policies and programs, instead of leaving these to the States) – a move which won 90% of all votes in 1967 – for many the “fair go” factor here is far less clear.

What about the prospect of a Voice that, in the wording of the proposed amendment, “may make representations”? In Yes camp messaging it’s just an “advisory body” that can’t make laws or fund programs. In No camp messaging it’s a permanent, publicly funded “lobby group” (on top of all the other advisory groups). Both sides agree that it has no direct, formal “veto” power. But the No camp remains concerned about indirect power to impede government decisions geared to wider public interests.

Example 2: the government and the opposition have both been willing to support a legislated “Voice” via Parliament, and also to see symbolic “recognition” enshrined in the Constitution. But only one seeks to enshrine both as a single act of recognition. For the Yes camp a “legislative” Voice risks being abolished by government without any immediate replacement body, leaving worthwhile local programs hanging (as happened to ATSIC with bipartisan support). For the No camp an enshrined Voice risks being a “Trojan horse” platform for activists who’ll seek legal intervention if they consider that their demands remain “unheard”.

Since both know that Parliaments will have power to design and update how it operates, the practical difference may be small. With no detail on its design written into the Constitution, a future Parliament could legislate to minimise the resourcing of the Voice to render it impotent, without actually abolishing it.

After months of partisan politicking on this in Canberra, the tragic irony here is that, as PM Anthony Albanese told Parliament in August: Both sides of parliament are saying they support constitutional recognition, and both sides of parliament are saying they support a legislated voice.

If so, whatever the referendum outcome in October, the next logical step for Parliament would (or could) be much the same. That is, to legislate the creation of a Voice body to fulfil the Constitutional change if Yes; and if No, to introduce a “legislative” Voice-type body instead. The best way to do this would be to establish a bipartisan committee to draft legislation to adopt/adapt the model outlined in the 2021 Calma-Langton report.

(This report was commissioned by the Coalition government in 2018, with a legislative Voice in mind. This was in response to the 2017 Uluru Statement’s call to enshrine a Voice in the Constitution. Another tragic irony: in 2018 the Labor opposition promised to enact a legislative Voice if elected in 2019. The idea then was to road-test it to limit the political risk of a scare campaign in a later referendum to enshrine it. In that scenario, there would be time for a constitutional convention to work through points of conflict and go to a referendum with a bipartisan approach to recognition (but in that process, deferring action on the 2017 Uluru call for Constitutional recognition). But this changed in 2022 when the newly-elected PM committed the government to enshrinement in the Constitution, to implement the Uluru “voice, treaty, truth” agenda in full).

4. A fourth Chart 1 task (keep it fair) is to recognise that on some points your opponent might be right.

Example 1: the scope of the Voice to Parliament was contested even by those who worked on the idea. In March, Constitutional law professor Greg Craven (a vocal Yes supporter) opposed the inclusion of advice to “Executive Government” in case it enmeshed government departments in legal challenges.

(Craven was later outraged to see the official No pamphlet quote his comment that this left the proposal “fatally flawed” with the Voice entitled to comment on “everything from submarines to parking tickets”. In the Australian he wrote that the No camp’s use of this quote (and the wider No case) were misleading. A chorus of reader disbelief ensued (as if to say: We’ve heard your voice already, Professor Craven. Try to understand how a boomerang works).

With no formal requirement to seek or to follow its advice, most experts see very little risk of the Voice “gumming up the system” (as Constitution expert Anne Twomey puts it). George Williams (another Yes camp legal expert) agrees that there would be no “deluge of litigation“. But he also confirms that (as a matter of process) the High Court could direct departments to consider “relevant” Voice advice (not sought but raised anyway); and then to “remake” (confirm or vary) prior decisions.

Example 2: the main Yes camp rationale for the Voice is that there’s no representative, co-ordinating national Indigenous body to advise governments on how best to meet regional and local needs. To this a No camp response is that an 80-member Coalition of peak bodies already works with the NIAA to consult and advise on “closing the gap” and to draw advice from hundreds of local Indigenous bodies. To complicate the issue further, these peak bodies are the groups Jacinta Price wants to see reformed. Warren Mundine sees the Coalition of Peaks as “stifling” the progress that was underway before. His concern is that the Voice adds yet another “layer of bureaucracy” to government decisions and program design.

In the Calma-Langton proposed model, the Voice would comprise 24 members elected by 35 chosen representatives of regional and local groups. As Marcia Langton notes, this would not displace already-established bodies – a concern of the Coalition of Peaks. But the Calma-Langton model, although designed to evolve over time and as Parliament sees fit, has not been confirmed by the Yes camp to indicate how the government intends to set up the Voice initially. When sceptics point to “lack of detail” it’s not enough to tell them to just read the 270-page report itself; or to point out that even in broad outline, no such “detail” would go into the Constitution itself. That aside, the Calma-Langton report – prepared for the previous Coalition government – was not designed to establish a constitutionally enshrined Voice (which may help explain why its proposed model would provide advice to both Government and Parliament).

Some critics add that we have an existing Minister for Indigenous Australians already getting advice from a range of representative groups on Close the Gap commitments; and that this fact alone weakens the case for another advisory group.

Overall, the lack of clear and simple indicative operational detail of the Voice – what Greg Craven called its basic “architecture” back in February – hasn’t helped the Yes campaign. Even for scholars and policy wonks (with no prior expertise on these topics), the idea of the Voice and the Yes camp messaging around it can be hard to decode: a once-only chance to take a modest, risk-free step that promises to unlock significant positive transformation; yet with no visible commitment to any real detail on its intended design; no clarity on how it would relate to the existing work of the NIAA and its 80 peak bodies; and no clarity on how it would relate to the wider Uluru “treaty” agenda.

This last point (treaty) has been framed by the Yes camp as not the referendum question, and so not (yet) up for debate. Given the government’s commitment to the full Uluru Statement agenda of “voice, treaty, truth” this deflection also has made the government seem evasive. In August political journalist Michelle Grattan warned in The Conversation that in refusing to be “more upfront about where treaty fits” the government risked leaving voters suspicious. Party politics aside, the uncertainty created can be expected to reinforce voter distrust of Yes camp messaging. And to lend credence to No camp messaging, which reads the proposed Voice as a shape-shifting “Trojan horse” (“Trojan koala”?) that conceals moves to undermine basic Australian ideas of “democratic equality” or the “sovereignty” of the Commonwealth Parliament to make binding laws.

Otherwise, the Yes side now presents its case plausibly enough: as formal recognition of First Nations’ status; and as a “safe” low-risk mechanism to help lift quality of life, social parity, economic agency and cultural recognition (or “self-determination“). As Noel Pearson put it to the National Press Club this week, a “safe and responsible middle path”.

The No camp presents the enshrinement of a Constitutional Voice as a strategic move by activists, political insiders and well-off elites to hoodwink ordinary Australians, opening the way to more radical change “just below the surface of the vibe” (as Janet Albrechtsen puts it). Some represent it as a portal to activate the Uluru Statement’s “symbolic declaration of war” (as Warren Mundine puts it). Perhaps leading to parallel “sovereignty” to make Indigenous laws that would be incompatible with Australian laws.

On this point it’s worth recalling that the proposed Constitutional change makes it clear that Parliament would have the final say on the “composition, functions, powers and procedures” of the Voice (as it would with a legislative Voice). But also worth recalling that in earlier discussions, some Voice proponents (such as Noel Pearson and Marcia Langton) recommended providing an “exposure draft bill” to show the public how it could operate once legislated by the Parliament.

5. A fifth Chart 1 task (keep it inclusive) is to refrain from contempt, abuse or gaslighting – say, by labelling the No camp “racist” or the Yes agenda “racial segregation”.

Confusingly, some followers of both the Yes and No camps have invoked an “apartheid” future for Australia if their side loses. This sounds like hyperbole. Its aim seems to be to weaponise fear and/or shame, to enlist support and/or silence opposition. Presumably among those who find the matter confusing and worry most of all that they’ll be on the “wrong side of hysteria” if they vote the wrong way.

As for “racism”, of course it exists in Australia and it’s relevant here. But in polling the top three reasons voters gave to say No didn’t reflect widespread racism or so-called “white supremacism“. They reflected concerns about equal civic rights (“It divides us”), model design (“There are no details”) and practical benefits “It won’t help Indigenous Australians”. (*****See the December update below for some research that confirms what concerned No voters most).

Otherwise, the Yes camp message that the Voice is about “indigeneity” not “race” (as Noel Pearson puts it) is at odds with its “No reflects racism” message.

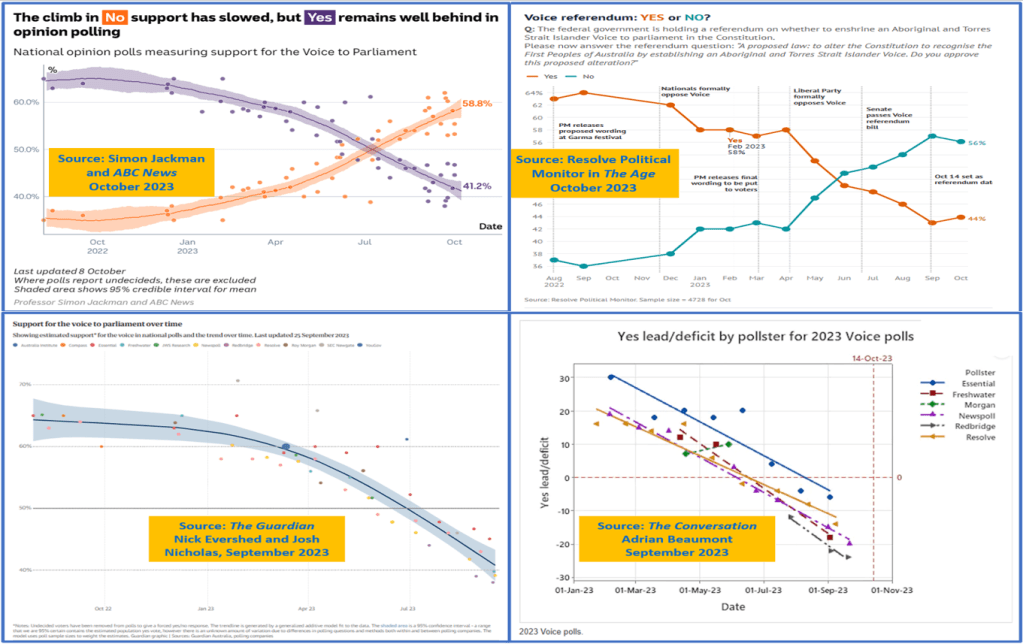

With indicative Voice support declining for months in opinion polls (see Chart 3, updated below) the Yes task has been to win undecided and “soft No” voters. An undertone of contempt in some Yes camp commentaries, and messaging that signals shaming tactics for those taking No camp concerns seriously, seem to be turning many of these voters away. If so, this runs counter to the advice of marketing experts in June, who outlined a “Gruen-style” campaign for Yes to win this way:

The classic advertising-for-social-change playbook would determine that Yes needs to shame people into voting “correctly” and give the impression they will be judged harshly for a No vote. It would paint the non-Yes as anti-progress (racist even) and determine that you are either with us … or against. Yes needs to realise it has many millions of people willing to help campaign, and harness that effort … Yes messaging … doesn’t need to be slick to be effective. But it does need to create what The Castle called ‘the vibe’…

As I write (in late September), many regard the referendum as doomed to fail on October 14. (At an estimated taxpayer cost of $450 million to conduct the referendum; and tens of millions more in privately-sourced campaign spending. The latter included significant corporate support for the Yes camp from major banks and mining companies).

Poll trends all indicate that a strong No result is highly likely (Chart 3). Time will tell, but in that scenario some sensible “Plan B” steps in Canberra (after a few months, when the referendum dust has settled) would be for parliamentarians on both sides to support an expert advisory committee that routinely reports to the Minister on Indigenous matters. In due course, this could:

1) Seek bipartisan support for the Parliament to create a legislative Voice-type body/bodies (such as a minimal version of the Calma-Langton model). This need not presume any further Constitutional amendment to operate. But it could leave this prospect open as a way of enshrining recognition in future, if the operational model delivers positive change. As now, the goal would be to create better Indigenous community consultation mechanisms, better program design, and better targeting of government expenditure, guided by Closing the Gap priorities and Productivity Commission reporting.

2) Have Jacinta Price as Shadow Minister co-chair a joint Parliamentary committee with Minister for Indigenous Australians Linda Burney. And appoint Indigenous experts (such as Noel Pearson, Marcia Langton and critics of their model such as Warren Mundine) to advise on the best “start-up” design for an advisory Voice (not enshrined in the Constitution).

3) Once it’s set up, seek further “Voice” advice on the effectiveness of Indigenous-related programs and expenditure run by government departments and existing representative bodies. And on new ways to address Closing the Gap priorities and to better co-ordinate the future work of the NIAA.

6. The final Chart 1 task (keep it in context) is designed to protect debate participants from social sanctions by their fellows for taking the “wrong” view.

For students in particular, these may arise when clumsy or clueless class discussion comments from the “wrong side” are (mis)quoted out of context, on social media especially. The risk in this is that they’ll be pilloried by peers and “right-thinking” opponents (see Tasks 1 and 5). And then they’ll self-censor, even when their insights could help enlighten others. This is not a good way to educate well-informed, engaged, socially responsible citizens. (Experts, educationalists and universities, take note!)

Conclusion

On October 14, ready or not, Australians will be compelled to vote Yes or No on what each considers wise, good, true (or not). In liberal democracies a “fair go” includes freedom of conscience, freedom to discuss and debate social problems openly – and in this case equal voting rights. But we can’t expect many Australians to engage with all this in much detail. Particularly those facing their own battles at a time of cost-of-living crises, rising homelessness, and overall trends of a decline in community well-being.

Whatever the referendum outcome, few will miss the culture-war tribalism on display in parts of the Yes and No campaigns. As Noel Pearson put it recently, he and Jacinta Price and Warren Mundine are “in furious agreement” on the problems faced by Indigenous communities. Whether we end up with an enshrined or (perhaps) a legislative Voice, the social, economic and cultural goals that Noel Pearson, Jacinta Price and other leaders have highlighted deserve wide support.

Reconciling differences seems a remote prospect at the moment, with mutual respect and two-way tolerance in short supply. To the extent that the hard Yes and hard No camps find a referendum win for the other side simply unthinkable, they should both enlighten up. After the outcome on 14 October, once the floods of dire prediction, blame-shifting and political point-scoring subside, common sense will return. And with it (whatever the wider governance settings), space for dialogue on a more bipartisan approach in Canberra, to seek better ways to close the gap for Indigenous communities.

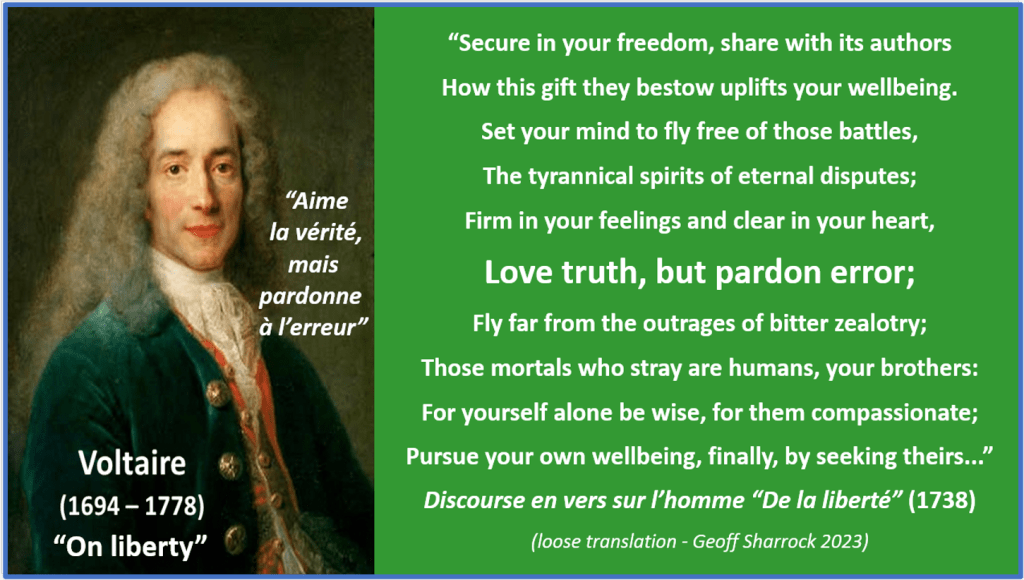

In his call to end the religious-war conflicts of 18th century Europe, the Enlightenment thinker Voltaire advised in his Treatise on Toleration: If you want us to tolerate your doctrine here, start by being neither intolerant, nor intolerable. His vision of the good society was one where individual freedom and community well-being (“self-determination” in today’s Voice context) were fundamentally reciprocal human rights that wise and compassionate citizens gave each other.

Recalling Noel Pearson’s idea of reviving Indigenous forms of “Enlightenment”, a new book on traditional laws by Marcia Langton and Aaron Corn offers insight on what this might mean. In her review of Law: The Way of the Ancestors, historian Janet McCalman reflects on how these communal societies were able to flourish in traditions that revered nature and landscape as dominant features of human existence, and that elevated reciprocity and shared responsibility over individualism: Indigenous Law has evolved to ensure the wellbeing of the society by building the inner wellbeing of individuals and collective wellbeing … As Langton and Corn emphasise, responsibility and reciprocity, not self-centred individual striving, build the good life, the good society, and the good world…

Meanwhile, Pearson’s call for better recognition and structural/systemic dialogue is framed as the only way to end a self-perpetuating “cultural war” in Australian politics. In this, his vision echoes what European intellectuals such as Albert Camus said in Paris in the aftermath of the Second World War. As Pearson put it to the National Press Club: This really is a test of whether our democracy can sustain a discourse for good. Pat Dodson put it in similar terms: It will test the idea that we are an enlightened, modern democracy. Whatever the referendum outcome, better dialogue across the Yes and No standpoints will be needed, to repair the damage of so much polemic to Australian ideas of democracy during these Voice campaigns.

Notes

My personal view on putting the Voice in the Constitution is that it’s a low risk move* with strong symbolic value, and with potential to make a positive practical difference. Parliament retains its own legislative and spending power to expand or restrict how it operates. So, whether in enshrined or legislative form, the Voice is worth a try. In either form, in the long run it can only succeed by being a credible, responsible body that tackles real problems and makes a visible difference on the ground. Unless compelling new No arguments arise, my vote on October 14 will be Yes, with reservations (as I rate the balance of risks and benefits).

At this stage of what has become a desperately combative, deeply polarising campaign, many readers may find my “even-handed” treatment of Yes and No arguments all too “academic”. My answer is that in a multicultural, liberal-democratic society like Australia, “being academic” has its virtues. Its capacity to engage in debate-as-dialogue can serve as an antidote to the endless polemics and partisan antics that animate today’s media ecosystems. These dynamics degrade public discourse, and turn public engagement on complex, big-picture issues like the Voice into needlessly divisive “zero-sum” games of political football.

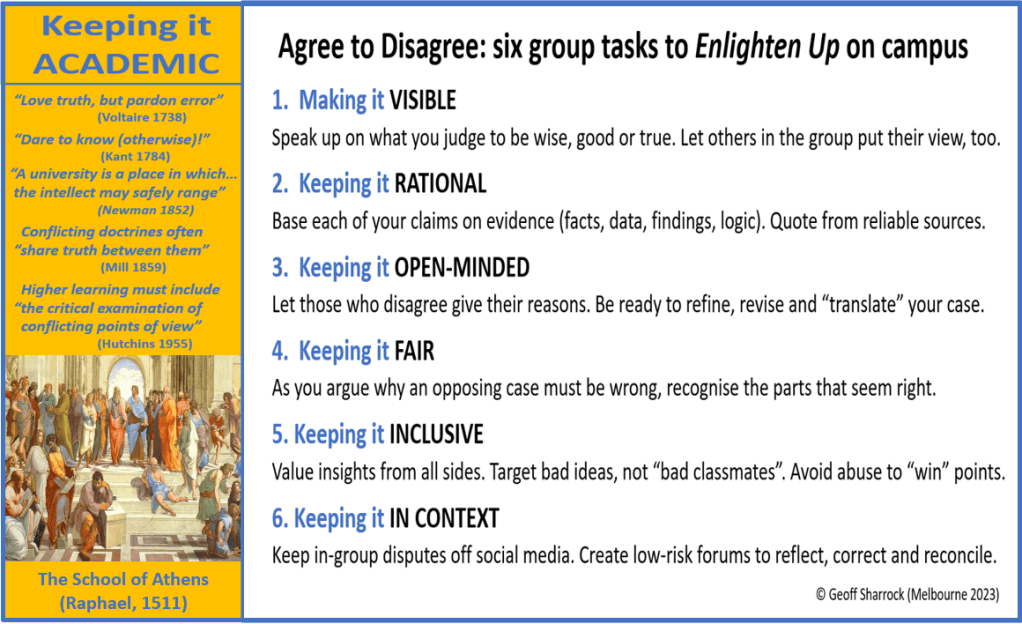

As Chart 2 below suggests, learning how to debate and disagree in ways that inform public deliberation on complex questions is something that could be taught more widely in universities. The 6 tasks offered here will be familiar to scholars. They reflect the kind of advice universities give students to guide “respectful disagreement” on campus (even though those of us who work in these institutions often don’t practice what we preach).

My Chart 2 “keeping it academic” list (similar text to Chart 1) is quite generic. It can be applied to a wide range of problems that many scholars and students research and study, and that societies badly need to get right. Even some Yes camp advocates admit that those leading the Yes campaign** could have done better in this case.

How else are we to work together to create better futures for our children, and a better, wider world for humanity? My short answer echoes Noel Pearson’s perspective: we can learn to enlighten up in our own deliberative, democratic practices. For this we need more leaders in every sphere of public life to show that it’s possible to do this better. Whatever the referendum outcome, for Australia the process of this debate can be what educators call a “teachable moment” in 2023, and in years to come.

*Update 6 October: writing in The Australian, former High Court chief justice Robert French outlines why the constitutional Voice would be low risk:

There are some simple propositions about the voice. The first is that it is created as an act of recognition… The second proposition is that the core function of the voice is to make representations to the parliament and the executive government. It cannot bind them. It cannot require legislative or executive action… Thirdly, the composition, functions, powers and procedures of the voice will be determined by parliament… Fourthly, as an advisory body there is little or no scope for successful litigation associated with its work. Neither parliament nor the executive can be legally bound by the constitutional change to do what the voice may suggest. It is also highly unlikely that the Constitution would be interpreted as requiring the executive government to take into account representations from the voice as a condition of the exercise of executive power. Fifthly, parliament can regulate the ways in which the voice can communicate to the executive and the parliament. It may specify the pathways of a standing committee or ministerial tabling of communications with the parliament. It may designate a particular minister as the recipient of representations to any part of the executive government.

**Update 7 October: writing in The Australian, constitutional lawyer and Yes camp advocate Greg Craven outlines who/what may be blamed if the No camp wins:

referendums… are indeed very hard to win, something Anthony Albanese did not appreciate sufficiently at the outset. He had some excuse. The prominent Indigenous leaders advising the Prime Minister along with his chosen legal coterie were saying he would get 70 per cent of the vote … But the Prime Minister’s covert drafting process, refusal to provide even basic architecture and reliance on platitudes rather than argument all have hobbled the Yes side… The real challenge in a referendum has always been the constitutional temper of the Australian people. They are logical constitutional conservatives… the slogan “If you don’t know, vote No” … has been used cynically as an all-purpose excuse by the No case. But the vilification of its adherents as constitutional cretins has been problematic. The challenge is that the “Don’t Know” position covers not only the deliberate constitutional ignoramus but also the thoughtfully unconvinced. They must be mightily unimpressed by condescension from Yes voters who may be no more intellectual than some adolescent “On a guess, vote Yes“…

***Update 9 October: Opinion poll results in media reporting in September and October.

****Update 20 October. Among the more insightful commentaries on the referendum outcome (60% No, 40% Yes):

In The Conversation, Michelle Grattan analyses the outcome (and the path not taken to legislate a Voice first) this way:

The Voice could be operating right now … Albanese was well motivated, but a great deal of harm has been done. The prime minister and others will say, the Indigenous people wanted a Voice in the constitution, not simply a legislated Voice. How could he ignore that, when he made his pre-election promise to pursue the Uluru Statement from the Heart in full? It sounds a compelling argument. Except when you consider the result. Instead of getting something, the outcome has been to achieve nothing … Australians almost never want to change the constitution, and many would not countenance a proposal that lacked enough detail and accorded one section of the community a particular constitutional place. To blame lack of bipartisanship, mis/disinformation, and racism is kidding ourselves. The (vote) margin was too wide … And yes, misleading information and conspiracy theories were flying around. But it’s insulting to suggest that so many voters were just duped … A central reason the Indigenous backers of the Voice campaign wanted it in the constitution was so a future (conservative) government could not abolish it. That insistence was understandable but had two flaws. First, the plan had parliament possessing wide powers over the body’s structure, so a later government could have emasculated it to the point of near extinction. The second flaw was this. If making the “perfect” (constitutional status) the enemy of the “good” (legislated only) was likely to end up where we are now, wouldn’t it have been better just to pursue the “good”? Albanese apparently thought he could deliver the perfect, which is extraordinary for a politician with his experience. But plenty around him must have known this was unlikely and should have persuaded him to confront reality…

In The Age/Sydney Morning Herald, Waleed Aly rejects pervasive “racism” as an explanation for rejecting the Voice proposal. Instead (with some echoes of Albert Camus on polemic in 1948), Aly analyses the outcome this way:

Referendums are mostly awful beasts … designed to take endlessly nuanced, complicated questions, and reduce them to a cold binary: yes or no … Yes advocates always insisted this was a simple, modest proposal. That’s true in the sense that it was meant to be an advisory body with no formal power. But as a referendum proposal, it wasn’t simple … Some didn’t like the Voice at all. Others were sceptical of its scope. Still others would be comfortable with a Voice, but only in legislation so it could be undone if things went wrong. Some feared it would be too powerful. Some thought it would be too powerless. Some just weren’t terribly engaged with the whole matter. And on it goes. But No – and simply No – obscures all that … we’re flattened into two camps that risk something even worse than polarisation … We risk not just disagreement, but mutual incomprehension. In that case, we look for shortcuts. And in political debate, perhaps the most tempting shortcut is to assume that your opposite number on an issue is your total opposite in every way … So, if we say our opponents are simply ignorant, or simply prejudiced, or simply duped, it’s often a way of declaring ourselves informed, enlightened, or savvy. That danger is very much alive now … the idea that Australians are simply so hostile to Indigenous people that they rejected the Voice out of some thoughtless, prejudicial reflex is difficult to square with its initial support in the polls, which was around 65 per cent … pollster Jim Reed … concluded that Australians will vote to “award equal opportunities to individuals regardless of their attributes”, but won’t vote for something that “treats individuals differently” … The power of Reed’s explanation is that almost all the various reasons people might vote No tend to go through it. From the most prejudiced to the most reasoned and sympathetic, each found cause to baulk at the notion of writing differential rights and representation into the Constitution. Viewed from this angle, the Voice referendum failed for exactly the reason the 1967 referendum succeeded. Both concluded that the Constitution should hand everyone the same basic status. Put differently, the Voice was a collectivist idea based on an assertion of group identity, trying to find a home in a broadly individualist Constitution. I think there were powerful arguments for doing so. But they were not easy or intuitive arguments to make. The Voice was always trying to thread this impossible needle. It had to present itself as modest, yet meaningful; to show it had no formal power, but would nonetheless make a practical difference. And it had to convince an electorate that it would achieve greater equality by treating citizens differently. In the end, that proved too complicated a task, the No vote too varied to assail, the referendum process too formidable a beast.

Also in The Age/Sydney Morning Herald, David Crowe analyses the outcome this way:

The great hope for the Voice turned out to be founded on an illusion. “This is something that should be well above politics,” Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said in Perth in February, in a claim he kept making until the final week of the vote. In fact, it was all about politics. It had to be. A vote by around 17 million Australians in a referendum was always going to be an exercise in democratic politics … The talk about lifting the debate beyond politics was wishful thinking or, worse, empty language that rang false with voters … The recriminations have begun over the serial mistakes: designing a model that was clearly unpopular with voters, deciding to pursue the model when it did not have bipartisan support, refusing to give way on wording that could gain broader approval, and campaigning poorly on a concept without enough detail. Labor history tells the true believers to cherish the heroic failure of a great cause destroyed by conservative enemies, but this erases the necessary questions about whether Australia could have had a different outcome … Yes campaigners who turn on voters now will only spread doubts about whether their attitudes were flawed from the start. Some want to blame voters for being too dumb to understand the constitution, or too gullible to see through the No campaign lies, or too racist to support help for First Australians. It is a fatal mistake in any reaction to a public vote. As readers of these pages pointed out in feedback throughout the campaign, many voters just did not like the model. They did not oppose help for Indigenous Australians, but they did not want to put the Voice in the Constitution.

In The Australian, Paul Kelly analyses the broader political context of the referendum this way:

This is the predicament of Western democracy … warning(s) that populist sentiment in Australia is likely to be greater than appreciated – with the voice referendum suggesting this – should be heeded given the economic squeeze is going to continue, real wages remain weak, living standards are under pressure, inequality is growing while progressive elites are likely to continue their drive to change our social and cultural norms. This is a recipe for serious trouble. The progressive cultural cradle is higher education and its method is cultural transformation. In its strongest form the progressive ideology says societies such as Australia have failed to come to terms with Indigenous dispossession, racism, sexism, patriarchy and monoculturalism in its beating heart, and this must be addressed in the schools and universities. In its milder yet influential variation financial and corporate elites push investment decisions based on environment, social and governance (ESG) criteria … The idea is that they should use their power to become agents of enlightened change – part of the unhealthy politicisation of nearly every aspect of society. These campaigns are conspicuous for their dubious lack of accountability. Whether corporates reassess after the voice vote remains to be seen. We are engulfed in an extreme adversary culture. This comes at the precise time we need to be supporting each other given growing economic tribulation. Power has shifted decisively to a professional, managerial, educated class that intends to use that power, a point readily understood by the voiceless majority … Binding up the wounds from the defeat of the Voice will be a long, difficult project. It will be even more difficult if the legacy is a more divided nation. That’s the risk. The people who have the power need to reflect upon how they lead and the consequences of their leadership.

In The Guardian, former Liberal prime minister Malcolm Turnbull analyses government “mistakes” this way:

There was never any prospect of the Voice amendment receiving formal Coalition endorsement. In 2017 the Labor opposition leader, Bill Shorten, was as pessimistic about the voice’s referendum prospects as I was. However … by the end of 2017 Shorten had changed his mind and Labor committed to support the voice as an achievable constitutional change. In February 2018 Shorten proposed that a Labor government would legislate to establish a voice before moving to constitutional change. He said: “In fact, I think it’ll be easier for a referendum to succeed and harder for a scare campaign to be run if we already have lived legislative experience of such a body.” At the time this self-evident observation was largely unremarked. And it gave Labor some options. If the voice was set up and operated for a while and the prospects for constitutional entrenchment looked bleak, then a different form of constitutional recognition could be pursued. But you would still have a voice … At some point Labor decided not to legislate the voice first … (this) appears to be the first of several occasions when Labor agreed to go along with the Indigenous leadership on critical issues – such as whether the voice should be able to advise the executive government as well as parliament. We can understand why they did so. The whole object of this exercise was to respect the agency of Indigenous Australians. I very much doubt establishing the voice first would have made the critical difference … As always the campaigns will be analysed and dissected in the greatest detail. But as is so often the case in politics, here there was one big mistake and then lots of smaller ones. Albanese will be blamed for losing an unwinnable referendum, Dutton for opposing something he could never have supported…

*****Update 11 December

Media reports of a new survey on the referendum outcome by ANU researchers (Nicholas Biddle et al) appeared in late November. Here’s an excerpt from their research findings (which confirms aspects of my analysis here).

There is no evidence in the data to suggest that Australians are against the idea of constitutional recognition in general. Of those who were willing to give an opinion as to what their vote would have been if the referendum was just about recognition those who would vote yes outnumber those who would vote no by a margin of almost five-to-one. The vote also did not signal a lack of support for reconciliation, for the importance of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders having a voice/say in matters that affect them, truth-telling processes, or for a lack of pride in First Nations cultures. All of these notions were supported in our survey by around eight-in-ten Australians … The data suggests that Australians voted no because they didn’t want division and remain sceptical of rights for some Australians that are not held by others. The data suggests that Australians think that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians continue to suffer levels of disadvantage that is both caused by past government policies and that justified extra government assistance. They did not see the Voice model put to them as the right approach to remedy that disadvantage … Australian voters are … not uniquely conservative. Australia’s referendum experience can be explained in part by reference to what appears to be three explanatory factors in other constitutional referendums, namely the need for a double majority, the use of compulsory voting, and the absence of bipartisanship … (and) specific characteristics of the 2023 Voice referendum … meant a yes vote was going to be a challenge. First, celebrity endorsement(s) usually depress the yes vote … The use of business and celebrity endorsements in Australia in 2023 may have provided voters a cue that the elites and the rich and famous were in favour of the Voice and, by implication, that this was against their interests. Second, in contrast to the 1967 referendum to include Indigenous Australians in the census—which was carried by a record majority—the Voice was seen as creating rights for small minority that were not held by others.

Further reading from this author on constructive disagreement on campus

Enlightening up – a framework for students in Australian universities (blog)

Free speech on campus calls for both hard heads and soft hearts (Times Higher Education)

Heterodox Academy project on viewpoint diversity on Australian campuses (blog)

Book review: Open Minds (and the French Review connection) (blog)

Feel free to disagree on campus – by learning to do it well (The Conversation)