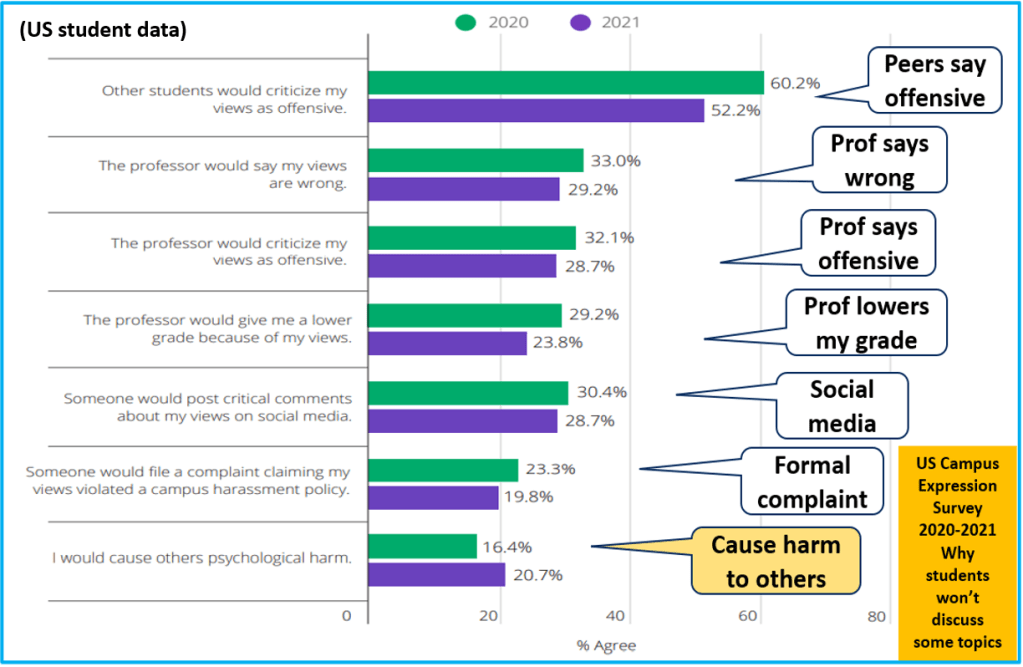

In Australia (as in the UK, US and elsewhere) we see claims that too often, students and scholars self-censor unduly, due to fear of sanctions in class or on campus or on social media. The extent and wider effects of this are very hard to measure reliably; we need more and better research. In Australia’s 2021 and 2022 Student Experience Surveys (see Notes), 3 in 4 undergraduates confirmed that they felt free to express (their) views” at their own institutions; and 4 in 5 felt free from discrimination, harm or hatred.

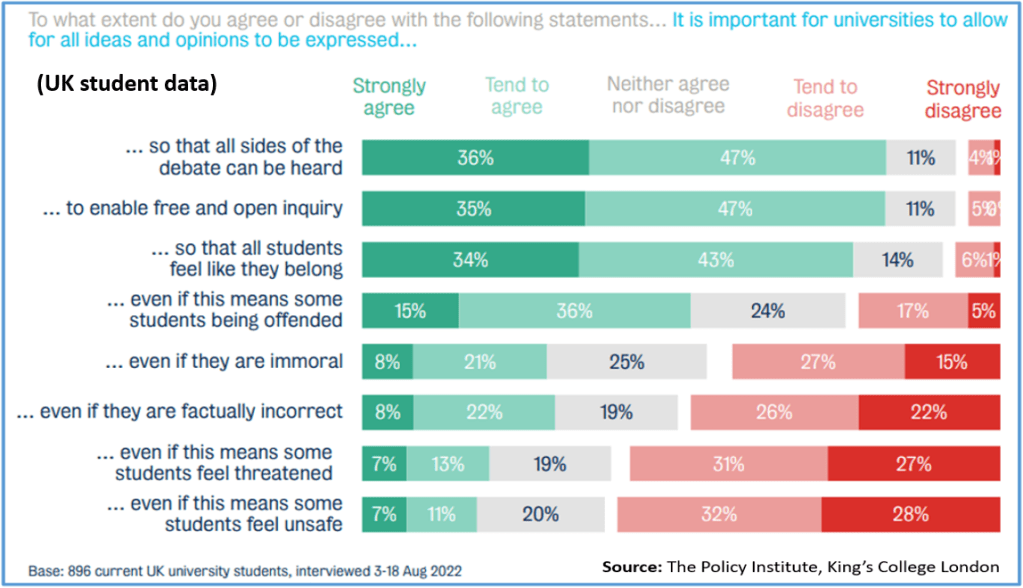

In more detailed UK surveys, 4 in 5 UK students supported “allowing all ideas and opinions to be expressed” so that all sides may be heard, and all students feel like they belong. But 3 in 5 did not support this if some students would feel threatened or unsafe. Many UK students agree that free expression is more important than ever in today’s world. On the other hand, for many, it’s important to be part of a university community where they are not exposed to intolerant and offensive ideas (see Notes).

Insights such as these should inform further Australian research. Since free exchange and fair treatment both enable wider, deeper engagement in study, good policy and practice are (often complex) balancing acts. As a principle, our scholars and students should be free to disagree within lawful limits. And also free from social harms such as abuse, vilification or defamation. Like scholars themselves, students live and learn in multiple contexts; and these often overlap. On-campus and on-line, students may share views with peers in class, with friends on-campus, and with family and social networks off-campus. To complicate things further, many students will reside in another country with different laws and different social norms, while studying on-line in Australia.

As well, some topics are sensitive or highly contested, as well as complex. How personal will the issues under discussion be for some students? How often will others self-censor for positive reasons, such as empathy for a classmate? With topics that are very personal or very political or both, some students may well feel more free to speak their minds on campus, or feel less at risk of some kind of psychosocial harm, than elsewhere.

Meanwhile, other arenas enable populist forms of intolerance, as seen often on social media. A vocal minority may silence more tolerant majorities who share some of its concerns, but don’t support all of its policy solutions, or all of its political tactics (see Notes). If this applies to a complex debate in a campus forum, insights that may enrich understanding on both sides of the matter may be left unexamined, or simply lost in translation – leaving less visible common ground across viewpoints.

For society at large, this often plays out as a kind of multi-polar viewpoint disorder. As a way of countering this, the radically inclusive university would promote what US scholar bell hooks called “radical openness”. This is a more mindful, empathetic approach to examining social problems where conflicting views are common, and where proponents often default to defensive routines such as stereotyping, shutting down or simply excluding others.

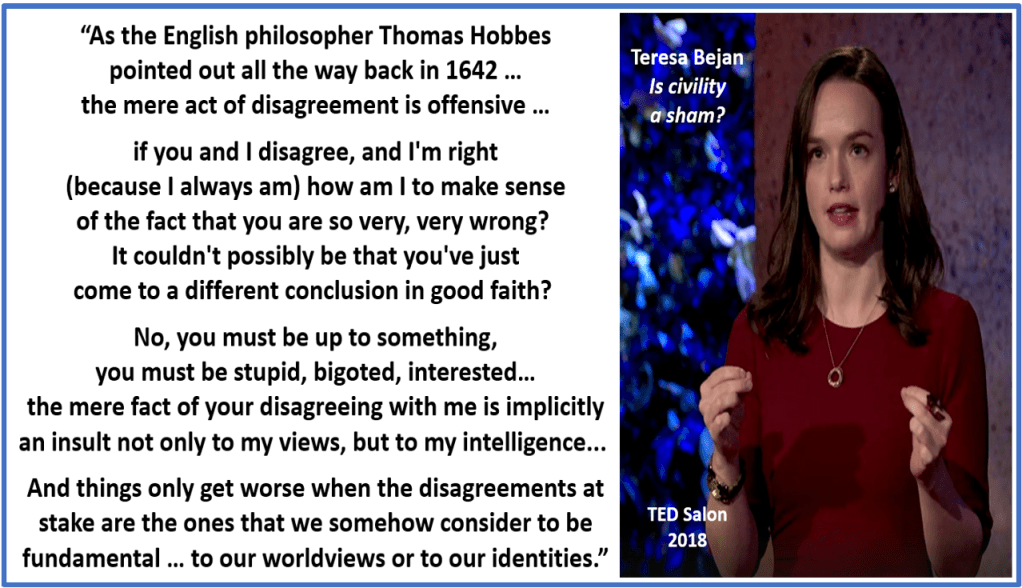

By making room to explore points of conflict and uncertainty, the framework I propose below limits the lazy presumption that to hold an opposing or minority view must just mean you’re bad or mad or both. Instead, it calls on participants to hear out and engage with (and often, to translate) opposing views in some detail, before judging their relative merits for the topic at hand. To enable such engagement the parties will need to presume rationality and good faith on both sides. But as Oxford University scholar Teresa Bejan argues, for most of us this is very counter-intuitive. To have someone openly disagree with your worldview in front of other people is often a disagreeable experience. Two-way tolerance in the form of “mere civility” requires effort and skill.

To counteract the effects of polarisation, the US-based Heterodox Academy provides some clear and useful guidance: to best promote open inquiry, viewpoint diversity, and constructive disagreement, we embrace a set of norms and values that we call “The HxA Way” … These values can help anyone foster more robust and constructive engagement across lines of difference … The objective of most intellectual exchanges should not be to “win,” but rather to have all parties come away from an encounter with a deeper understanding of our social, aesthetic, and natural worlds. Try to imagine ways of integrating strong parts of an interlocutor’s positions into one’s own. Don’t just criticize, consider viable positive alternatives. Try to work out new possibilities, or practical steps that could be taken to address the problems under consideration…

Hard(er) heads, warm(er) hearts: a framework for more productive disagreement

In an Australian higher learning context, the factors just outlined call for a lot of two-way tolerance and open-mindedness. In any diverse group where firmly held views may differ widely on some topics, it will take self-awareness, skill and patience to listen and learn, and to disagree well. In recent work on viewpoint visibility in Australian universities, I make a case for a hard heads / soft hearts framework to promote more inclusive and more open-minded discussion of difficult topics.

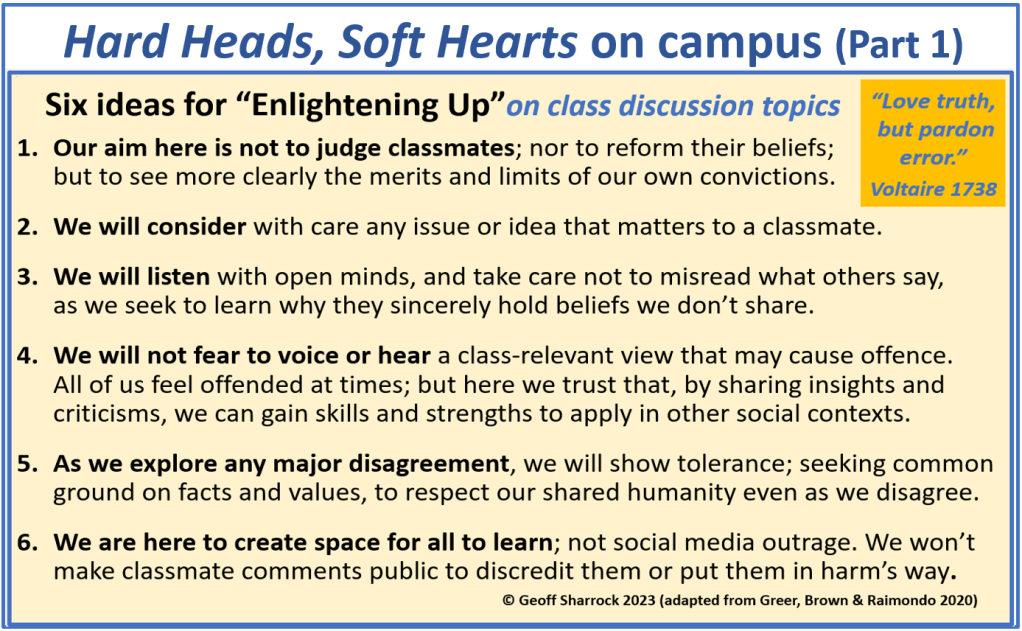

The “soft hearts” part is a set of study group norms. These call on students to share their thinking openly, and in turn to consider classmate concerns with care. The ethos is one of multilateral engagement, supported by the norms of intellectual humility and intellectual charity that Heterodox Academy promotes. As one university leader puts it, this should be a “safe forum” where unpopular views may be heard and their merits openly debated, without fear of being “silenced” (see Notes).

Since one of the risk factors that many students consider is that a classmate may disclose what they say in class, leading to criticism by peers (and others) on social media, the final point proposes a kind of Chatham House rule where individuals are not tagged for their remarks in other contexts.

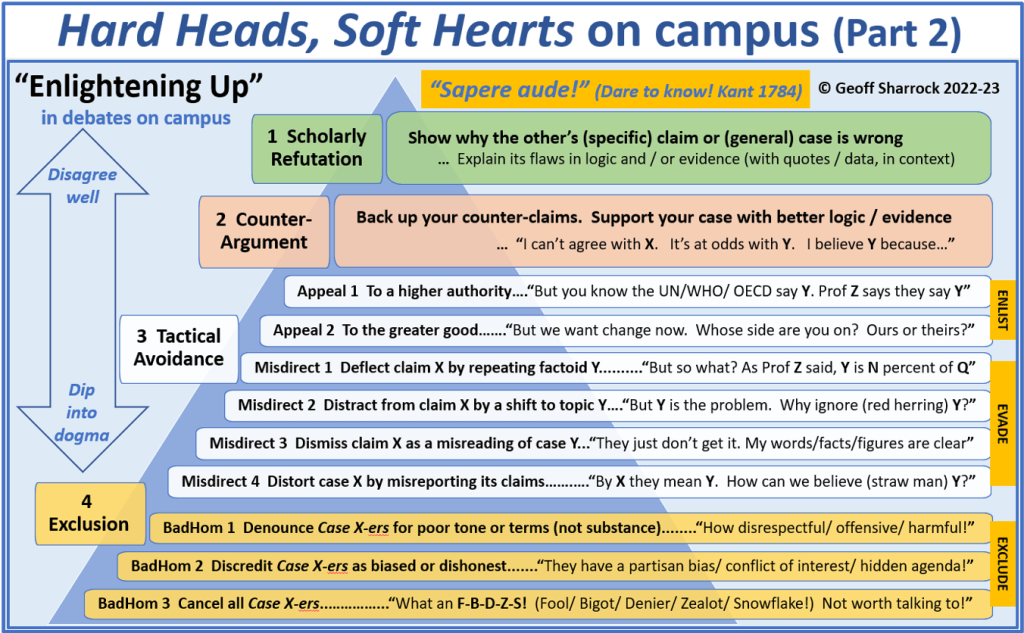

With this deliberately inclusive, multilateral approach, students may still refrain from challenging others’ ideas. The risk in this is a retreat to the default setting of “all opinions here are equally valid” without establishing real common ground on facts or logic or values. To help counter this, the “hard heads” part is an argument quality pyramid. It calls on students to disagree well by aiming high. Here the winning argument will rely on more compelling logic and/or stronger evidence. Lower down is a list of common rhetorical avoidance tactics. These can be used to deflect or distort the substantive point an opponent is making to support their own case, instead of disputing or refuting the point directly.

At the very low end, exclusionary tactics rely on meta-argument allegations, personal accusations or ad hominem forms of denunciation (BadHom123). The predictable effect is to shame and/or silence (at the extreme, to slander) opponents by framing their view as biased or offensive or harmful or abusive; or by labelling them a “bigot” or a “snowflake”.

The examples of name-calling at BadHom3 are at odds with the call by Heterodox Academy to target bad ideas, not “bad people”. As one of our Australian university leaders says of such tactics: This is intellectually lazy and is the antithesis of how we should behave in a university. And yet, as other leaders warn, terms such as “hate speech” (or even “respect”) can be misapplied to rule out discussion of any view labelled “offensive”.

(Note to administrators: university leaders should always strongly endorse “respect” as a campus norm; but to strictly enforce “respect” as if it were a formal, definite rule would unduly constrict academic freedom of expression among scholars, and the open exchange of views that higher learning requires in Western universities. For a recent Australian example, see the Peter Ridd court case.)

None of this means that any scholarly debate should be a free speech free-for-all. Participants need to consider other views on their intellectual merits. This includes the concerns of those who find your own view offensive, to know their reasons for this.

To help guide students as they grapple with difficult topics, scholars may at times need (as a Cambridge philosopher puts it) a spine as well as a brain (see Notes). As well, institutions need to promote clear, simple and accessible guidance that scholars and students can refer to. In the example below, the UK’s Equality and Human Rights Commission offers very clear guidance on the basic rules of engagement for higher learning institutions and their student communities – including, of course, the right to protest.

As I noted in last year’s project: many problems universities confront in this area are multi-faceted and intertwined. Their complexity goes well beyond the left-right labels and culture-war narratives that have politicised and polarised so many current debates. The hyper-partisan politics so often seen off-campus makes the normative preconditions for higher learning in Australia difficult to sustain. And these culture-war factors won’t go away anytime soon. They are embedded in wider fractures in public discourse – multi-polar viewpoint disorder – well beyond the control of universities. These include mass media and social media dynamics that routinely promote intolerance and antagonism instead of the rational dialogue and collective problem-solving on which liberal democracies rely as pluralist multi-cultural societies.

In conclusion…

Along with clear policy and guidance, university communities need to promote a culture of openness based on widely shared understandings of academic freedom and free speech principles (see Notes). Both charts in the framework I’ve outlined fit the findings of the 2019 French Review and the Model Code principles it recommended to Australian universities. The framework assumes university policies that:

a) protect individual freedom of expression; and

b) protect student and staff well-being; and

c) promote diverse and inclusive campus communities.

Combined, they reflect a hard-won Enlightenment principle of two-way tolerance as we dare to know (to judge for ourselves what is good or true). As the philosopher Kant put it in 1784: Sapere aude! (Dare to know! Have the courage to use your own understanding!) is therefore the motto of Enlightenment … This Enlightenment requires nothing but freedom… to make public use of one’s reason in all matters … A Clergyman is bound to preach to his congregation in accordance with the doctrines of the church he serves … But as a Scholar he has full freedom, indeed the obligation, to communicate to his public all his carefully examined and constructive thoughts concerning errors in that doctrine…

For students in class settings, tolerance does its work when the ideas that one group finds most meaningful are at odds with those of others; or when a core belief for one group has lower priority for others. This accords with what a UK university leader has called the radically inclusive university. In this kind of institution (another UK leader argues) modes of debate are less gladiatorial … not merely scoring points, but building consensus (see Notes).

The proposed framework also aligns with some advice from UK philosopher Bertrand Russell in a BBC interview in 1959. His two-part “message to future generations” made an intellectual point and a moral one: When you are studying any matter … ask yourself only what are the facts and what is the truth that the facts bear out. Never let yourself be diverted either by what you wish to believe or by what you think would have beneficent social effects if it were believed … Love is wise, hatred is foolish. In this world, which is getting more and more closely interconnected, we have to learn to tolerate each other. We have to learn to put up with the fact that some people say things that we don’t like … if we are to live together and not die together we must learn a kind of charity and a kind of tolerance which is absolutely vital to the continuation of human life on this planet.

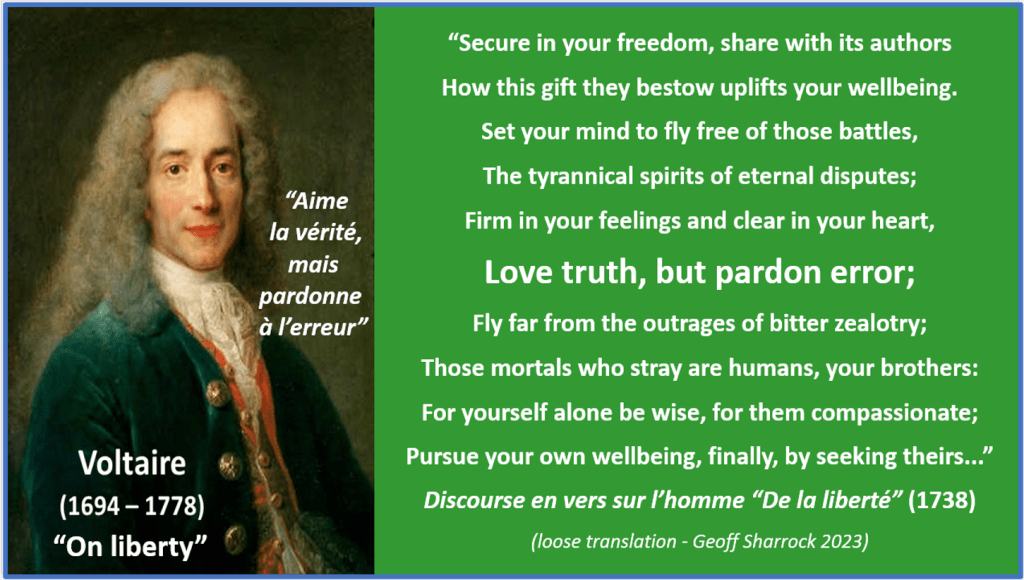

Many thinkers echo these ideas today. As “radically inclusive” scholarly communities set up to seek, share and strengthen knowledge and understanding reliably, universities need coherent sets of principles to guide inquiry-based learning, with few if any critical-thinker no-go zones. Here open, intellectually honest debate can do its work, in a never-ending project of enlightening up. In his Treatise on Tolerance in 1763, Voltaire put it well: If you want us to tolerate your doctrine here, start by being neither intolerant, nor intolerable. He believed it was vital to cultivate and protect critical thinking, to promote the good and just society. And (perhaps reflecting his own experiences of imprisonment and exile) he did not regard intellectual independence and freedom of conscience as at odds with a concern for the rights and sensibilities of others. His idea of freedom was as a reciprocal gift of compassion, grounded in a common humanity.

Today’s radically inclusive university communities, in which students can express their views, be themselves, and enable each other to enlighten up without sacrificing freedom of conscience, might adopt as their informal motto: Love truth, but pardon error.

Notes

Those interested in applying my work on this topic can contact me directly at geoffksharrock@gmail.com.

The framework outlined here is informed by commentary from university leaders in Australia, New Zealand and the UK; and by recent Australian, UK and US data on student views (see below). For a detailed discussion of the value of viewpoint visibility in higher learning, see last year’s long-read Discussion Paper, which concludes:

In sum: campus cultures must accommodate the fact that in Australian universities, scholarly dissensus often runs deep. In practice, what does it take to seek and share and strengthen truth and knowledge reliably? Put simply: if the aim is to SEEK KNOWLEDGE ALWAYS, they must urge scholars to PROFESS TRUTH ALWAYS. But, since speaking truth to power poses risks, they have a duty of care to scholars, to PROTECT ACADEMIC FREEDOM ALWAYS. But, since unlimited free expression may harm others, they must also urge scholars to RESPECT RIGHTS ALWAYS. But, since the idea of “respect” is open to concept creep, campus cultures must also uphold the right to disrespect (and better yet, to debunk) fallacy, delusion and dogma. As a call for civility on campus, respect is a laudable norm which (when minds collide and viewpoints clash) may also be a risible rule to enforce. Tolerance underpins the radically inclusive university, not the enforcement of ‘respect’ as such: RESPECT (BUT NOT ALWAYS) … With practice in the disciplines of tolerance on campus, freedom from hate (and from harmful speech that violates rights) could be promoted by way of more debate, not less: MORE DEBATE, LESS HATE...

Related commentary from Geoff Sharrock (see links below) refers to the 2019 French Review, a 2021 book by Evans and Stone, Open Minds, and a 2022 project on viewpoint visibility, funded by Heterodox Academy.

Feel free to disagree on campus … by learning to do it well (theconversation.com)

Book review: Open Minds (and the French Review connection) (geoffsharrockinmelbourne.net)

Peter Ridd, the High Court and academic freedom (geoffsharrockinmelbourne.net)

Repression or ‘polite reticence’? Unpacking self-censorship (Times Higher Education)

Campus free speech needs hard heads, soft hearts (Times Higher Education)

Hard heads, soft hearts: why our universities need both (geoffsharrockinmelbourne.net)