Introduction – the Australian context

In Australia (as in many other liberal democracies), ours is an age of high anxiety and deep uncertainty. We are a successful multi-cultural nation where half the population was either born overseas or has an immigrant parent, and where 1 in 4 people speak a language other than English at home. We have weathered global shocks (financial crisis, pandemic crisis) comparably well. But we face social cohesion risks. We have seen new lows of trust in major political parties, business enterprises and public institutions; more highly partisan debates and public discourse; at times more fragile relations between communities; and growing intolerance for others’ beliefs and opinions.

As commentator Paul Kelly wrote recently in The Australian: Our high support for multiculturalism is a national asset but overwhelmingly dependent on the sense that Australia’s cohesion and national unity is retained … the future success of Australian democracy depends on integrating into a united country people from different cultural backgrounds and different religious backgrounds … Yet this model of political liberalism is now under worldwide assault … On display is the contemporary regression to clans, group identities, self-righteous partisans and a media increasingly surrendering to ideological views of the world. It is harder to find common ground.

This sense of greater fragmentation was apparent in the May 2022 federal election. As commentator Waleed Aly wrote of the outcome in the Sydney Morning Herald: our politics has fragmented to the point there are no natural majorities in Australia anymore. We now have majorities of dissent – so we can remove a government via a coalition of discontent, but any new government becomes vulnerable to a new dissenting majority…

Perhaps liberal democracies are entering an era of mass-scale multi-polar viewpoint disorder. In the US, according to Jennifer Kavanagh and Michael Rich, there are strong signs of so-called truth decay: a more pervasive blurring of the lines between honest facts or opinions and various forms of falsity. As they see it, The most damaging consequences of Truth Decay include the erosion of civil discourse, political paralysis, alienation and disengagement of individuals from political and civic institutions, and uncertainty over national policy. In Sweden a study of media literacy by Jutta Haider and Olof Sundin views the effects of the information crisis as fragmentation, individualisation, emotionalisation, and the erosion of the collective basis for trust, all with implications for not just the individual, but also for democracy, and ultimately the organisation of society. And here in Australia, Derek Wilding and Anne Kruger’s report on the rise of information disorder refers to disinformation (known to be false and spread to cause harm); misinformation (not known to be false and spread with good intent); and malinformation (correct but confidential, and spread to cause harm).

Like it or not, most of us now live in a globally connected information ecosystem significantly shaped by what Columbia University’s Emily Bell calls the tabloidisation of everything. Most media platforms feature clickbait headlines aimed at widening market share. On social media, readers will find no end of group-think silos to inhabit, as writers engage in relentlessly spin-doctored phrasing to promote an agenda, polish a brand, or parade a personal sense of inner virtue. At the same time, social media platforms generate crowd-sourced waves of outrage, to denounce any view that offends some segment of the political spectrum. Once routinely hyperbolic, performative modes of expression become the dominant norms of public discourse – with nothing to be taken at face value, but in constant need of decoding – the community trust that invests legitimacy in democratic modes of deliberation and decision making is eroded.

Recent accounts of the corrosive effects of social media in the US point to the collateral damage of culture war and cancel culture dynamics. Last year columnist Anne Applebaum wrote in The Atlantic: the modern online public sphere, a place of rapid conclusions, rigid ideological prisms, and arguments of 280 characters, favors neither nuance nor ambiguity. Yet the values of that online sphere have come to dominate many American cultural institutions … Heeding public demands for rapid retribution, they sometimes impose the equivalent of lifetime scarlet letters on people who have not been accused of anything remotely resembling a crime.

More recently in The Atlantic, social psychologist Jonathan Haidt further diagnosed the US malaise this way: Social scientists have identified at least three major forces that collectively bind together successful democracies: social capital … strong institutions, and shared stories. Social media has weakened all three … First, the dart guns of social media give more power to trolls and provocateurs while silencing good citizens … Second … more power and voice to the political extremes while reducing the power and voice of the moderate majority … extremists don’t just shoot darts at their enemies … (but at) dissenters or nuanced thinkers on their own team … Finally … social media deputizes everyone to administer justice with no due process. Platforms like Twitter devolve into the Wild West, with no accountability for vigilantes…

Indirectly the Applebaum and Haidt critiques confirm a point made by UK comedian Ricky Gervais in 2020 (itself an echo of Adam Smith’s frank and honest impartial spectator in 1759): The worry now is, social media amplifies everything. If you’re mildly left-wing on Twitter you’re suddenly Trotsky … if you’re mildly conservative, you’re Hitler … if you’re centrist and you look at both arguments, you’re a coward and they both hate you.

Culture-war levels of polarisation and intolerance on social media echo the religious-war persecutions that appalled Voltaire in 18th century Europe. His 1763 Treatise on Tolerance prescription for peaceful co-existence was clear: If you want us to tolerate your doctrine here, start by being neither intolerant nor intolerable. While not a free speech absolutist (he opposed slander as well as intolerance) Voltaire found the official enforcement of orthodoxy, for example by the public burning of newly published books in Paris, absurd.

“I disapprove of what you say but I will defend to the death your right to say it.”

Australian public discourse reflects less multi-polar disorder than is apparent in the US. But recent Australian cases echo the trend. In her account of several, University of Melbourne law professor Katy Barnett observed in 2018 that: In Australia witch-hunts are bipartisan … Pitchfork-wielding mobs have always existed, but never have they been able to form in a matter of minutes and get people fired within hours … we could tweet something at the breakfast table before heading out the door for work only to find that when we arrive we don’t have a job … we are all governed by this rapid-growth wrath and the possibility that expressing our honest opinions on social media could destroy our careers … I feel as if the Overton window of acceptable political ideas is shifting to polarized extremes, and views which I have long held … may now be regarded as unacceptable on parts of both right and left …

Scholars may have their research dismissed as racist on social media by other scholars, despite its intent and integrity, and despite all efforts to prevent their findings from being misrepresented in the media by culture-war commentators. Meanwhile, an outspoken Australian-Muslim activist who sparks conservative outrage with a social media post may, as Deakin University professor Fethi Mansouri puts it, get “Yassmined” – not least in media outlets where commentators routinely insist on free speech rights.

Liberal-democratic cultures give priority to free thought and free expression. Yet a notable trend worldwide has been for social media dynamics to compress all claims – and all political positions – into extreme shorthand (hashtags, soundbites, symbols). The ensuing lack of context or nuance transforms these communicative arenas into the antithesis of campus-based scholarly inquiry. Everyday terms become loaded with new subtexts; X must now mean Y; hype springs eternal; and misinformation may go viral, creating mini-pandemics of misguided applause or (more often) dismay and outrage.

As University of Sydney linguistics professor Nick Enfield puts it: Falsehoods are dangerous, and when they spread they can cause real harm. Yet we seem blindly willing to share stories whose truth we are not sure of … One reason is that we too easily believe that it’s actually true. We all suffer from confirmation bias, the readiness to accept evidence that confirms our views, and to reject evidence that contradicts them…

Instead of talking and listening with each other, social media participants often talk at or past or about each other. Trivial points of difference, often expressed in terms that no-one has clearly defined, may morph into all-or-nothing conflicts. Like Shakespeare’s Montagues and Capulets, parsing the subtext of an ambiguous public gesture (Do you bite your thumb at *us* sir?), any substantive point of disagreement may melt into a bonfire of the inanities on social media (if not a physical brawl on a Verona street).

In a hyper-connected, hyper-critical world, such meltdowns may flow from a person’s use of everyday terms whose unspoken subtext is re-coded by shifts in context or audience. An activist slogan such as Defund the police, one analyst notes, becomes a “Rorschach inkblot test” for readers who place different meanings on the phrase, and assume different policy agendas. An innocuous use of a newly-coded phrase may have serious consequences, even in higher learning settings where care for context supposedly matters. Example: in a university in Canada a Dean of Graduate Studies was stood down from his role for posting a tone-deaf Tweet (which, once aware of its social media currency, he deleted with an apology) with the hashtag #AllLivesMatters (sic). He thought he was engaging in an intellectual discussion. Readers thought he was engaging in a political messaging contest.

As the Roman Inquisition apparently assumed when condemning Galileo in 1633, scholars really need to see the big picture – in political terms. To the adage: be careful what you wish for we now must add: be careful what you “like” on social media. Not least for those who work in major cultural institutions, Twitter in particular turns out to be “LinkedIn for those seeking professional job-loss“.

As well, by creating mass audiences for bite-sized news and opinions, social media platforms have led to the rise of predominantly performative self-expression (often labelled “woke” – another contested term whose meaning seems to range from we support social justice to those intolerant lefties). To its critics the aim of performative self-representation is not to explore issues or engage in open-minded debate on possible solutions, but to crowd-source approval for a chosen stance, and win social status in the process. So, for all its risks (and despite his aversion to ever writing anything down), Socrates today might conclude that the unmediated life is not worth living. But for an independent viewpoint on a hot-button topic, the net effect will remain what we might call a “Voltaire drought” in campus-related contexts, despite university policies that say the usual things about free expression.

We need universities to “enlighten up” (1) Public discourse

If this rough sketch reflects recent Australian trends, and a plausible prognosis of the national outlook, the issue is how to avert the risk of decline into evermore partisan division and shifts toward societal dysfunction. Which mix of cultural and economic settings best supports our future as a good (safe, fair, sustainable, prosperous) society? For Australia’s diverse communities to continue to adapt, advance and thrive, we all need to enlighten up.

More than most other institutions, universities are well placed to pursue this kind of project. At its core the university mission is to seek and share and strengthen truth and knowledge reliably so that communities, societies and humanity can benefit. (And indirectly, to reassess and reconcile competing doctrines. And in turn – often far less reliably wherever vested interests lurk – to refute prevailing dogmas.)

As historian Hannah Forsyth notes, the Murray Report on Australian universities made the case for academic freedom and how it contributes to public discourse this way, in 1957: Here is one of the most valuable services which a university, as an independent community of scholars and inquirers, can perform for its country and for the world. The public, and even statesmen, are human enough to be restive or angry from time to time, when perhaps at inconvenient moments the scientist or scholar uses the licence which the academic freedom of universities allows him, and brings us all back to a consideration of the true evidence and what it may be taken to prove … No nation in its senses wishes to make itself prone to self-delusion…

As they enter tertiary study, students are invited to acquire knowledge and skills (and disciplines and sensibilities) that will prepare them to be insightful thinkers, engaged citizens, capable professionals, community leaders and advocates for progress. Critical thinking, creative imagination and the communicative and argumentative skills needed to contribute to informed debate and deliberation on complex matters will remain essential. The disciplines higher learning aims to instil can help to inoculate communities against confirmation bias and the viral spread of misinformation, to mitigate the risks of herd immunity to reason.

To the extent that universities succeed in these aims, future graduates will be capable of helping institutions shape new strategy, inform national efforts to adapt to geopolitical and technological shifts, support social and economic development across diverse communities, and promote human progress in myriad ways, at home and abroad.

We need universities to “enlighten up” (2) Campus life and intellectual culture

For their part, universities are not immune to the mass culture dynamics that work against this project; they too may need to enlighten up. In a recent address University of Melbourne vice-chancellor Duncan Maskell put it this way:

One of the most critical areas for us as we go about our daily lives in the University – and one that can be very hard to get right – is finding a balance between behaving respectfully to members of our community as persons versus tolerating others’ opinions. Part of the challenge for everyone in this moment, I suspect, is … constantly boiling down complicated situations to the assumption that there is a simple answer … This can then lead to opposing groups forming, who think that the way to disagree is … to start throwing metaphorical bricks at each other. This is intellectually lazy and is the antithesis of how we should behave in a university…

The rise of cancel culture on US campuses has been widely discussed. But the extent of the problem and its wider effects are hard to map. Self-censoring on campus, due to fear of overt or covert social sanctions, may be largely invisible. (As well, the meaning of the term cancel culture is contested and its usage varies widely.) A recent paper by Harvard University’s Pippa Norris drew on a worldwide survey of political scientists’ views in 2019, to examine whether cancel culture in academia is a myth or a reality: Intolerance of dissenting views, especially among the progressive “far-left,” it is argued, silences conservative perspectives, brainwashing students into “politically correct” views. Norris notes that the cancel culture label itself has generated more political heat than intellectual light (as seen in US politics where Donald Trump denounced it as left-wing totalitarianism).

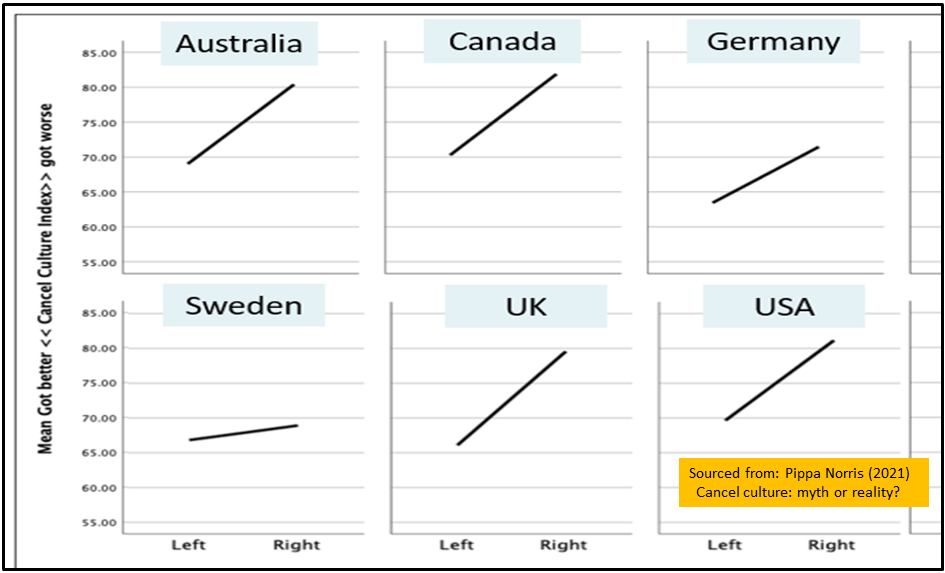

The 2019 study of political scientists shed light on the incidence of the problem in academic contexts in a wide range of countries. It used 3 survey items as proxies to create a cancel culture index, that indicates whether academic life had become better or worse over the previous 5 years. The survey items were: Respect for open debate from diverse perspectives; Pressures to be ‘politically correct’; and Academic freedom to teach and research.

Norris observes that in predominately liberal social cultures such as the US, self-identified right-wing scholars were most likely to perceive that they faced an increasingly chilly climate (while in more traditional cultures such as Nigeria, it is liberal scholars who report that a cancel culture had worsened in colleges and universities). As shown in the selection at Chart 2, she notes further that the US pattern, where those on the right report worse experiences of the cancel culture, is reflected in the cases of Canada, Australia and the UK, among others.

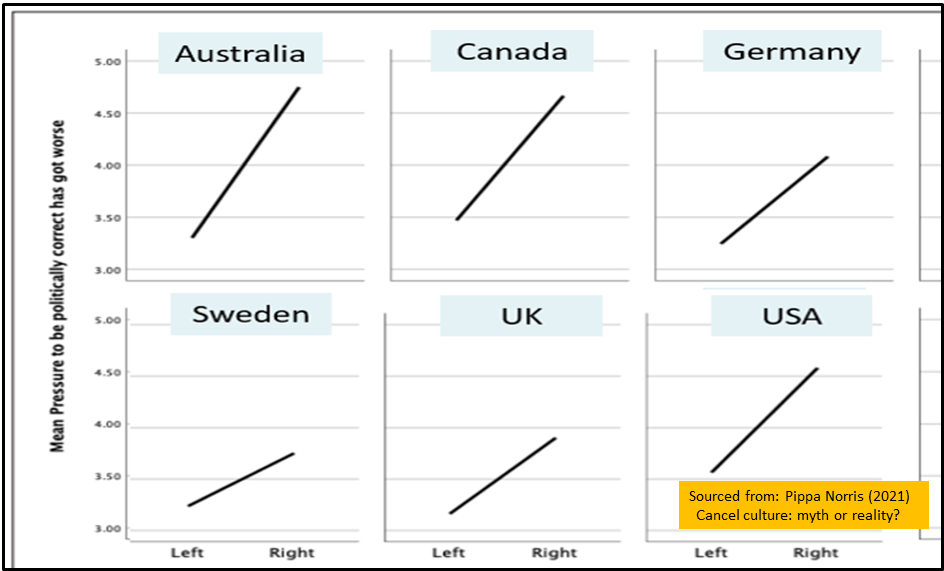

In the case of Australia, Chart 3 indicates that concern about rising pressure to be politically correct looms large for more conservative political scientists. Norris concludes: Left-wing faculties are more likely than those on the right to believe that there has been little or no change in respect for open academic debate and pressures to be politically correct. Given the predominance of progressive liberalism on college campuses, those on the left may be unaware of the experience of more conservative colleagues—and may deny that there is a problem based on their personal experiences…

In the Australian context any pressure to be politically correct on campus will be amplified by the structure of our academic workforce, which includes a significant segment in insecure employment. One project participant (higher education policy professor Andrew Norton at the Australian National University) put it this way: Short term contracts were not an attack on academic freedom as such … but when most people particularly most younger people are on these, that reinforces the other mechanisms – such as peer review and the promotion system – to adopt whatever is the orthodox set of views, the orthodox set of research priorities. And these things do have the effect of making people more cautious, narrowing the range of topics that are investigated, and narrowing the perspectives that might be expressed within those topics… In other words, for those seeking an academic career in Australia, Voltaire’s 1752 remark may still resonate: It is dangerous to be right on matters where established men are wrong.

We need universities to “enlighten up” (3) Leadership engagement

In Australia in 2022, it is unclear how interested university sector leaders are in these questions. On other fronts the sector has had a rough few years and is still recovering from pandemic-related disruptions. Recent changes to the funding model for higher education now need further reform. As well, a change of federal government has opened up the prospect of further reforms on a range of other matters. In sum, many sector leaders will be fully engaged on other pressing issues.

These system-level challenges aside, the sector has also had a few rough years dealing with the politics of the topics examined in this project. In 2018, enough concerns had been raised about a purported free speech crisis to prompt Education Minister Dan Tehan to commission a review of the statutory rules on free speech and academic freedom, and university policies in this area. From the outset the French Review drew defensive responses from the sector. Peak body Universities Australia declared that free expression was alive and well; that between them some 40 universities had over 100 policies in place already; and that, just a week before the Review was announced, sector leaders had reaffirmed their longstanding commitments to these enduring principles. Not only was such a Review not needed, the argument went, but critics were misguided to claim any kind of crisis without firm evidence; or to call for the adoption of a local version of the Chicago Principles in Australian higher education.

In the event, the Review found no free speech crisis from the available evidence. But nor did it confirm that (as the UA response had put it): A culture of lively debate and the vigorous contest of ideas is strongly in evidence on Australian university campuses. In fact, there was no systematic evidence to back this assertion either. The Review didn’t survey students or staff to assess either of these narratives (this was not part of its terms of reference); and the sector itself had not conducted such a survey.

Meanwhile, self-declared conservative scholars such as University of Queensland law professor James Allan (commenting on this project) argue that all is not well: I get a steady stream of junior conservative academics and students who come to me and say they want out … Some (academics) just keep quiet. Some quit … (the French Review) is correct in a formalistic sense that there’s basically no free speech problem because almost everyone is a progressive, left-leaning academic … For the very small number of conservatives, though, there is certainly a free speech problem and loads of self-censorship.

For its part, the Review‘s examination of institutional policies identified problems serious enough to warrant recommending statutory changes and a Model Code, that universities could adopt or adapt on a voluntary basis. The Code was designed to enable the sector to take ownership of these issues. In part, to reduce the political risk of heavy-handed regulation; but also to minimise the risks to free expression writ large in existing university policies. For example, the risk that causing others to feel offended or insulted (in some policies, regardless of intent to do so) could be restrictive enough to inhibit expression of prevent group discussion of sensitive topics; or lend authority to calls to sanction scholars or students who did so. While not based on any particular overseas model – the Review referred to UK and US examples as the most relevant – the Code’s policy stance echoed a key feature of the Chicago model. It made clear that lawful speech which caused offence must normally be permitted, so that scholars could exchange views freely, without fear of penalty.

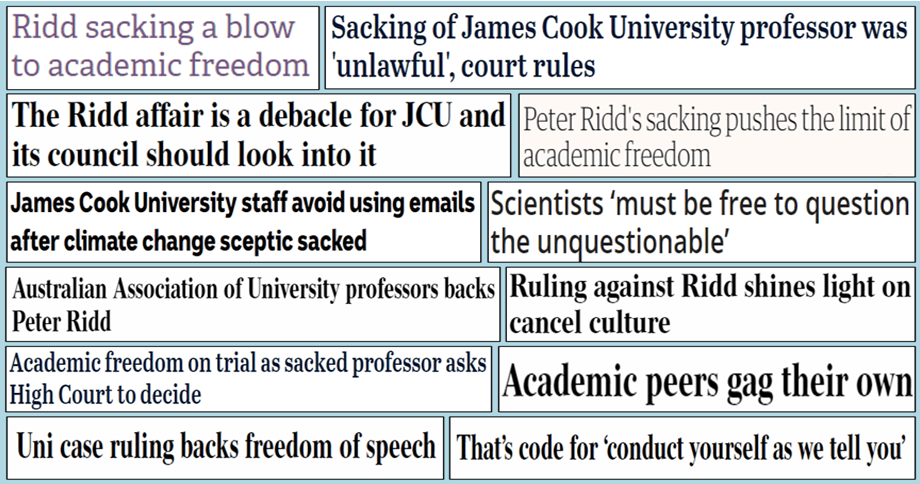

While not all university leaders were dismissive toward the Review (as it noted, the Innovative Research Universities group advised that they had been discussing the Chicago Principles as a point of reference for a group approach to these issues), in 2019 the sector’s peak body response drew adverse media commentary. Its public line on the Review‘s no crisis finding was that this implied no problem at all (and implicitly, no need for a Model Code). Perhaps it was hoped that the political pressure would fade with a widely expected change of government. Unfortunately, this response coincided with the widely unexpected outcome of the May federal election; and with the first of three court rulings on the controversial sacking of Professor Peter Ridd by James Cook University.

After the election returned the (then) Coalition government, the Education Minister urged the sector to implement the Model Code during 2019, and again in 2020. As well, the first court ruling on the Ridd affair found that he should not have been sanctioned for disrespectful criticisms of others’ work in his field. His academic freedom rights, properly understood, protected such critiques within the usual lawful limits (such as defamation or vilification). The details that came to light included alleged incidents of misconduct that all three courts, including the High Court in 2021 found trivial – such as his remark in a personal email to a sympathiser that universities were Orwellian.

News of the email search led many other JCU staff to stop using their office email accounts. For the wider public the Ridd case held a rare public mirror up to a process of intramural managerial cancel culture. In other circumstances this may well have remained invisible, under the university’s confidentiality rules. As it went through 3 courts over a period of more than 2 years, the dispute drew a lot of bad press, from across the political and media spectrum (see Chart 4). It illustrated how disproportionate cancel culture tactics may shred the norms of academic work – whatever sector leaders say about institutional commitments.

Directly, such incidents of apparent persecution may damage only the career of the scholar concerned. But the chilling effect may be pervasive, creating unseen icebergs of self-censorship among local colleagues, or peers in other universities. The wider culture war politics hardly helped mitigate the chill factor. No doubt, at least some other sector leaders looked askance at JCU’s handling of the matter. One former Vice-Chancellor said so openly, in media commentary.

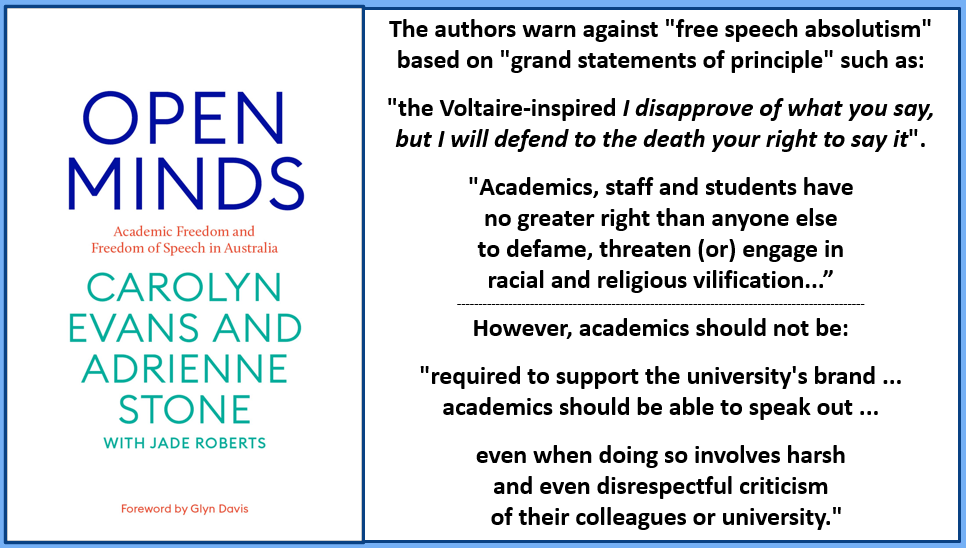

In this context, particularly for scholars with minority viewpoints, an official free expression is alive and well narrative reinforces the impression that one critic of the sector’s response to the French Review (public policy commentator Paul Kelly) called phony assurances. As with the wider Review project, positions on the substantive policy and practice issues here are not reducible to a two-sided culture war narrative. Conservative commentators – such as those at the Institute for Public Affairs – offered vocal public support. But Ridd’s rights in the matter also drew public support from the left-leaning National Tertiary Education Union; from the Australian Association of University Professors; and from legal scholars Carolyn Evans and Adrienne Stone (in their book Open Minds), among others.

While the Review did not take any stance on the Ridd case, the court findings illustrated the systemic problems Robert French had identified. The Review warned that policies that made respect mandatory could be applied too restrictively; that apart from negative public perception and the risk of political intervention, incidents of apparent persecution could have a wider chilling effect on free expression; and that even with clearer, more coherent rules, institutional culture (which depends largely on leadership) could support or undermine academic freedom, in practice. In the Ridd case (citing legal philosopher Ronald Dworkin), the High Court dismissed as absurd JCU’s argument that it could mandate respect without undermining intellectual freedom: however desirable courtesy and respect might be, the purpose of intellectual freedom must permit of expression that departs from those civil norms.

In other words, as George Orwell put it in The Freedom of the Press in 1945: Unpopular ideas can be silenced, and inconvenient facts kept dark, without the need for any official ban. As one project participant observed in this context: So much stems from the institutional leaders and the cultural settings they create. So, the policy settings are an enabler, but they are not the driver in many cases (of campus controversy). It’s incredibly important to have those policies and procedures, and they become a very useful tool. But they are the servant of the culture, in my experience.

Another participant (Deakin University’s academic governance and standards director Matt Brett) made a similar point in relation to the Model Code: I question whether the one size fits all Model Code is being embraced in institutional cultures, and whether it is an effective tool for equipping students and staff to exercise delicate judgements on when and how to speak one’s mind. In my experience, and in certain institutional, cultural and stakeholder contexts, there is not an opportunity to do anything other than to follow the corporate line. Apparent Model Code compliance is not going to solve the broader social issues, nor localised challenges that may arise in relation to academic freedom and free speech.

On this point the Ridd case was instructive. The university applied loosely worded, overlapping policies in ways that conflated a duty to respect a person’s lawful rights with a demand to display respect for their opinion (or status). In this sense, respect in an academic context may be both a laudable norm and a risible rule. Taken literally, such rules offer scope for Orwellian levels of intolerance that unduly limit otherwise honest, robust, lawful, scholarly critiques. They allow otherwise reasonable concerns to promote civility on campus to trump the commitment to protect the free expression of scholarly opinions and an open exchange of ideas. (As the Chicago Principles put it: although all members of the University community share in the responsibility for maintaining a climate of mutual respect, concerns about civility … can never be used as a justification for closing off discussion of ideas…)

The Ridd case also illustrated why a Model Code could fortify the formal protections for free inquiry when other priorities (such as concern for institutional reputation, or for stakeholder relationships) become salient. It made clear that to the extent of any inconsistency with other policies, this Code prevails.

Apart from its policy implications the Ridd case illustrated what University of Wollongong social scientist Brian Martin has called censorship backfire, where the adverse publicity costs far outweigh any institutional benefit. Overall, then, the politics surrounding the French Review in 2019 and 2020 were dismal for the university sector. That aside (as some participants in this project confirmed), the effort required for universities to review their existing policies in response to the Model Code was considerable. The Education Minister commissioned a further review of their progress. By the end of 2020 (with universities now grappling with pandemic-related disruption) the Walker Review concluded that many were still not fully aligned. This reflects the technical complexity of these questions, in part due to the range of statutory and policy statements that govern their operations. As one project participant from the University of Sydney outlined at the May webinar (higher education policy and projects director Tim Payne), those that were fully aligned achieved this by embarking on significant internal review projects, with many stakeholders involved.

In sum, while universities clearly do value academic freedom and free expression, and are likely to have drawn clearer policy lines as a result of the Review, in 2022 these may be topics that institutional leaders would prefer to put aside, to focus on other challenges.

We need universities to “enlighten up” (4) Better research data on campus climates

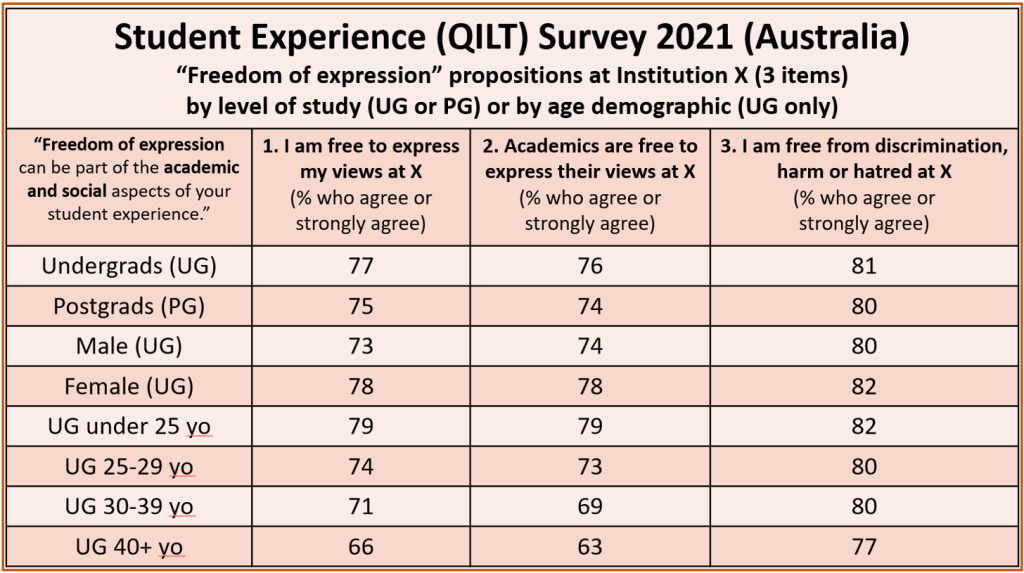

Australia lacks good data on questions such as the extent to which students or staff self-censor on campus, due to fear of some form of sanction. At the time of the French Review‘s report the Institute for Public Affairs presented some apparently concerning results from its own student survey, in which 41% of 500 respondents agreed that: I sometimes feel unable to express my opinion at university. During this project the latest QILT survey of student experience was not yet available. Conducted in 2021, it includes 3 items: I am free to express my view at (institution); Academics are free to express their views at (institution); I am free from discrimination, harm or hatred at (institution). (See Notes for updates on this.)

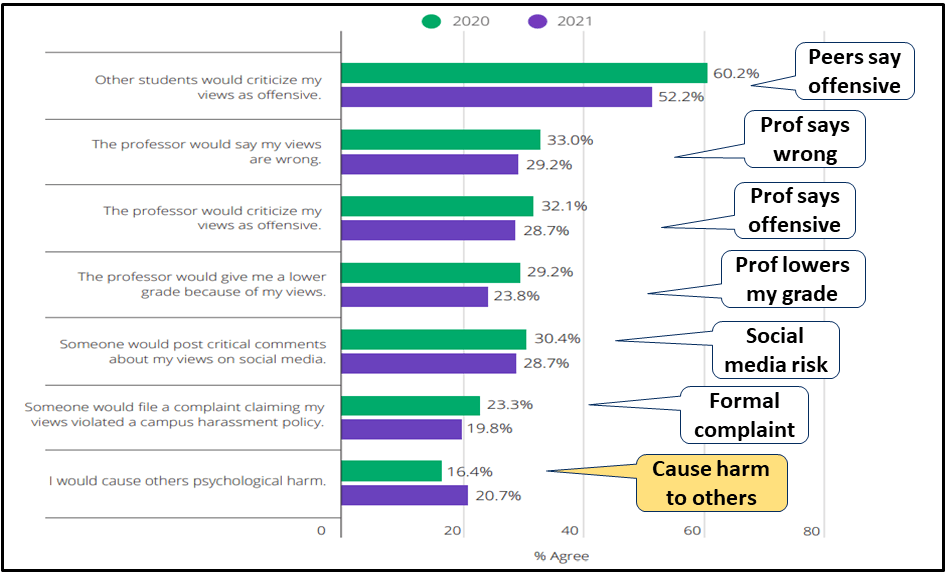

At the May and June webinars for this project, we discussed whether Australian universities (or perhaps a new Association promoting academic freedom and viewpoint diversity) should conduct (or call for) student surveys based on the Heterodox Academy’s Campus Expression Survey. Looking at snapshots of the latest CES results for US students, we noted that a challenge here was how best to distinguish negative forms of self-censoring on controversial topics – such as fear of peer criticism in class or on social media – and positive self-censoring, such as consideration for others on sensitive topics of concern to them personally (see Chart 5).

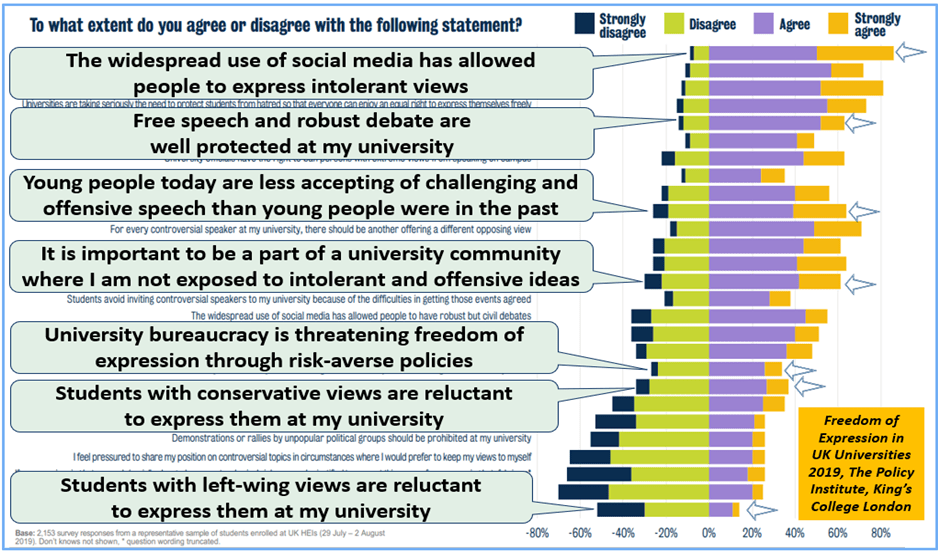

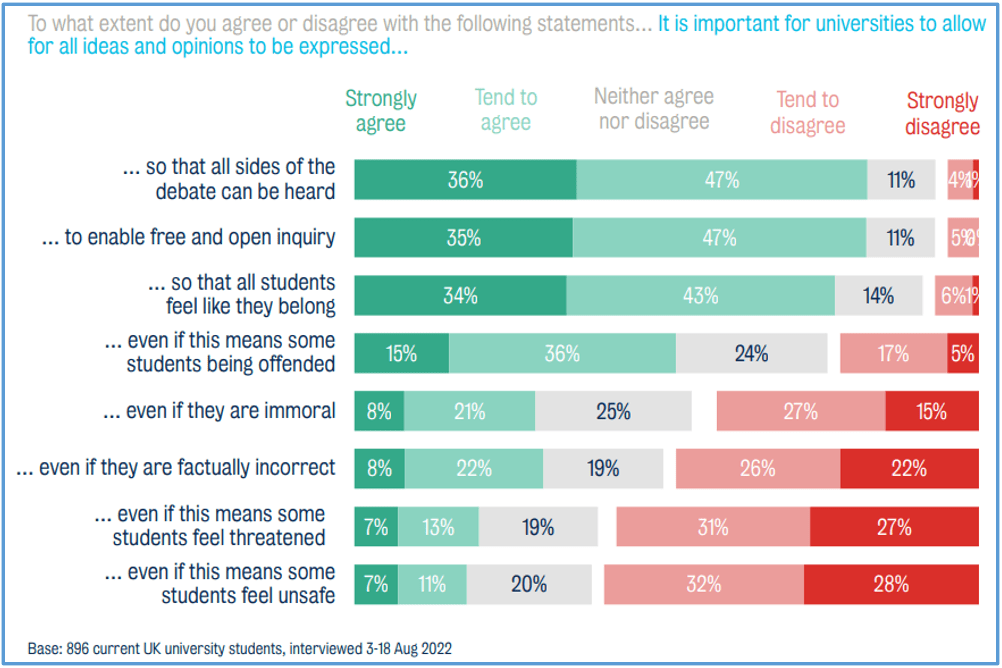

We also looked at samples of data from an extensive 2019 survey of UK students conducted by The Policy Institute at Kings College London (Chart 6). Across 27 items it mapped student views on whether social media enabled intolerance to be widely expressed, whether free speech was well protected on campus, their expectations about exposure to intolerance on campus, whether conservative students were less willing to express their views, whether university policies were too restrictive toward free expression, and other related issues.

Should Australian universities decide to conduct a detailed survey on these matters, the Policy Institute study offers a promising starting point. It highlights the diversity of attitudes among students towards the balance university policies must strike between promoting free speech and protecting others from harmful speech.

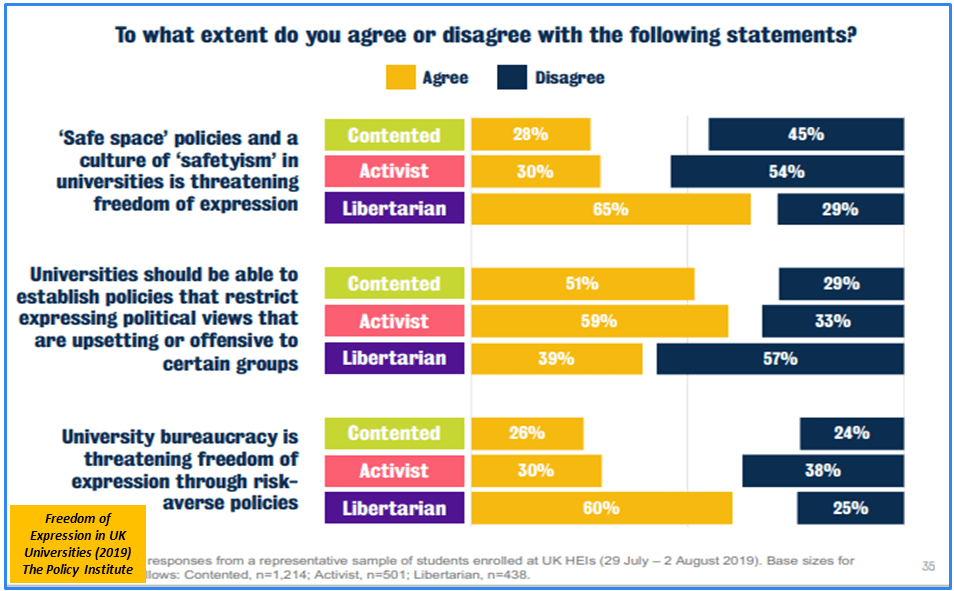

Those students the UK study identified as activists (1 in 4 of all surveyed) or as libertarians (1 in 5) had different views on where to draw these lines (see Chart 7). Most libertarian students were concerned that free expression was at risk from restrictive university policies and what the survey called a culture of safetyism. Most activist students were not; and this group agreed that universities should, as a matter of policy, be able to restrict the expression of political views that some groups found offensive.

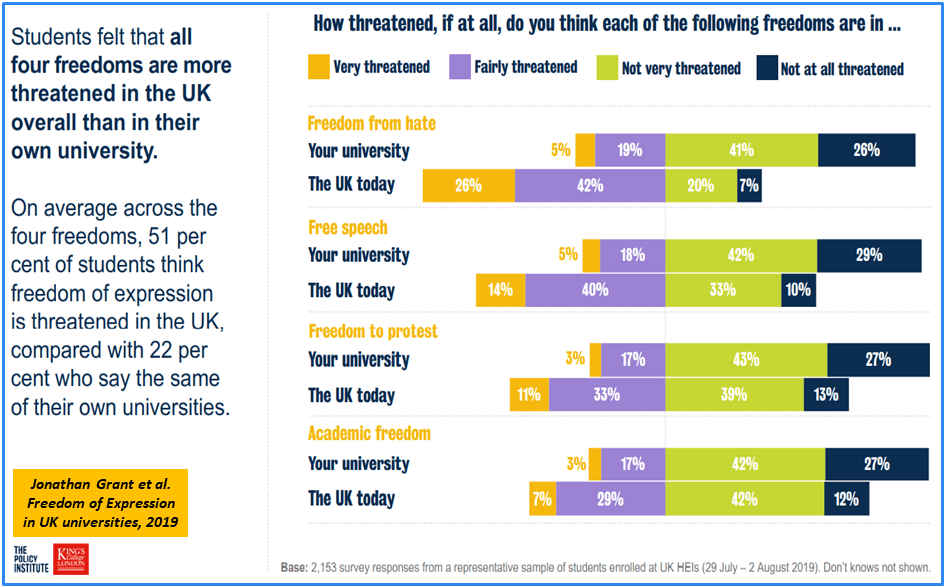

In a parallel survey the Policy Institute study also sought to capture wider contextual factors such as student perceptions as to whether free expression on-campus was more or less at risk than it was off-campus. An interesting finding in the UK study was that both free speech and freedom from hate were considered more at risk in off-campus contexts (see Chart 8).

To speculate, it’s possible that student activists on UK campuses promote greater restrictions in part as a response to the more pervasive intolerance encountered off-campus. Students who routinely experience harassment or discrimination – say, on the train as they make their way to campus – are likely to be more sensitive to any echoes of this they encounter when they get there. This may put them at odds with libertarian students. The latter may not endorse the intolerance seen off-campus, at all. But they still may not agree with activists on what the most relevant values and acceptable terms should be, to frame the issues and assess what the best campus policy should be.

The same issue may arise with what scholars publish or teach, or how they teach it, in fields of study which touch on these issues. Recent Higher Education Policy Institute student poll data (of 1000 undergraduates) suggests greater intolerance on UK campuses toward scholars who teach “offensive” material. In 2022 some 36% of those surveyed agreed that If academics teach material that heavily offends some students, they should be fired. This compares with 15% agreeing to this proposition in a previous (2016) survey.

HEPI report author Nick Hillman interprets those results this way: most students want greater restrictions to be imposed than have tended to be normal in the past. This may be primarily for reasons of compassion, with the objective of protecting other students, but it could also reflect a lack of resilience among a cohort that has faced unprecedented challenges...

In 2021, roundtable discussions at two Australian universities asked 46 students how they understood the term diversity, and how they thought universities could improve intercultural engagement during study. A report by the Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher Education concluded from these consultations that: While students generally hold an expectation that healthy debate should exist at university, there was some disagreement as to whether controversial opinions can or should be shared in class. Some participants suggested that it is possible to share, while other participants indicated that to do so is uncomfortable, and the response to sharing ‘opposing’ ideas is extreme. Students perceived there to be a dominant way of thinking at university and noted that the roles such as tutors can be very influential. Participants reported being known to one another in the classroom environment as a supportive factor in engaging in discussion, and they noted that speaking up in class can be intimidating because of a range of variables; including gender, power dynamics, language, personality, confidence, and the attitude of their tutors.

We need universities to “enlighten up” (5) More constructive debates on campus

These impressions of student perspectives in Australia, and the survey data snapshots on the institutional balancing act in UK higher education, raise 3 general issues of relevance to Australian universities:

- how to make complex, often polarised topics more discussable on campus;

- how to inform and enable wider and deeper public debates about them; and

- how to build student resilience to contend with the more unthinking forms of intolerance they may encounter off-campus, or on social media.

A US pilot program run as a partnership between two higher learning institutions and the Bridging the Gap project seeks to tackle these issues. It introduces the problem this way: too often the call for “diversity” has been reduced from the true promise of engaging diverse people and ideas as a practice to a commitment that one is simply expected to hold. Today a “call-out” or “cancel” culture has taken hold where dismissing other points of view is often encouraged and where being exposed to alternative viewpoints can in some cases be considered “dangerous.” What is demanded currently is protection from the “other,” and what is applauded is shutting those voices down … it is important to note that this dynamic exists on both progressive and conservative campuses.

In the Australian and New Zealand university sectors, leaders attuned to these issues argue that universities should model more constructive debate. In his address University of Melbourne vice-chancellor Duncan Maskell put it this way: We have an important role to play not just on campus but for the world, in finding answers to questions and solutions to problems, but also in dissecting and explaining issues … Respectful listening as well as robust expression of views are centrally important … At university we have the obligation and opportunity to model more productive modes of disagreement and debate … We can respond to unhealthy trends in the popular discussion of issues by modelling vigorous, informed discussion and debate in our classrooms, on our campuses and through our social media platforms and our participation in external media outlets.

And in New Zealand last year, University or Auckland vice-chancellor Dawn Freshwater put it this way: Our academics and students must be free to advance and challenge ideas, even controversial ones, without fear of being attacked or ‘silenced’. Indeed, providing a safe forum for this to happen is one of the most important functions of a university … allowing the expression of an idea does not imply endorsement by the University … We must hold to account ideas that compromise reason, contradict knowledge and undermine truth … Affording scrutiny to freely expressed ideas, to distinguish those that have substance and value from those that do not, enables institutions like ours to deliver the benefits of our intellectual scholarship to the society we serve, by empowering rational and well-informed public discussion … So, a call to action to institutions of higher learning. We are the exemplars … We should speak bravely and freely, but with respect, reflection, deliberation and intentionality. This is fundamental to universities; it is also a much broader issue for societies…

Both leaders refer to the need for universities to promote more rational and constructive debate on campus; and also, to model these disciplines in wider social arenas, through their teaching and research and public engagement practices. To this we can add a third agenda item that emerges from the US and UK survey data on the risk of psychological harm: to build student skills and resilience through courses of study and campus forums, that students can then apply in other, less tolerant social contexts.

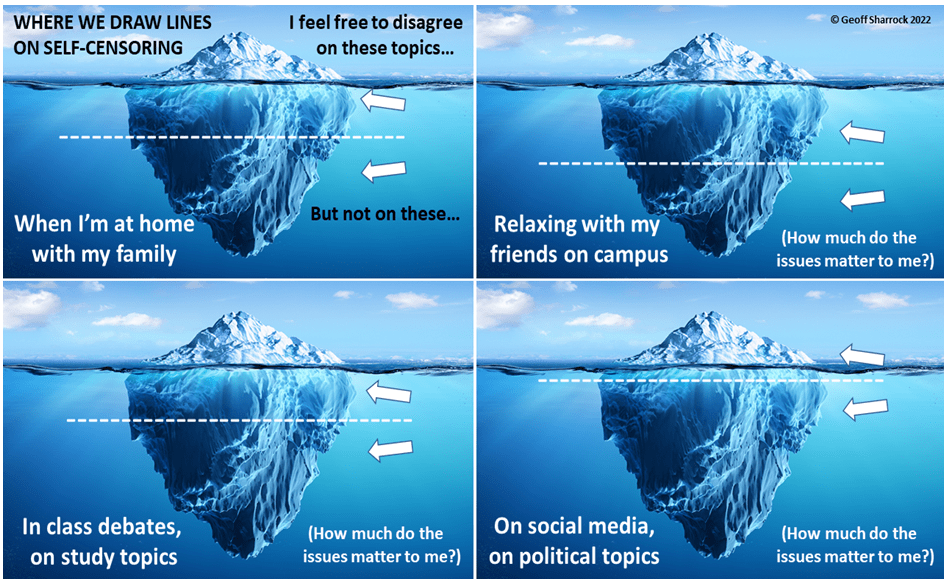

These context discussions expand on a theme built into this current viewpoint diversity visibility project from the outset. The premises are that (as the English poet John Donne put it in 1624) “no man is an island”; but also that, on the question of expressive conduct in different group settings, everyone’s an iceberg.

For the March and April interviews, an “iceberg” model (Chart 9) was used to illustrate how contextual factors may lead students to self-censor more or less on different topics in different circumstances: (say) at home with family members, or on campus with close friends, or in class where the topic is a sensitive one for classmates. As elsewhere, students in Australian universities often inhabit multiple contexts at the same time. They may engage in social media exchanges in tandem with classroom or cafe exchanges on campus (or in a residential college); and are likely to encounter different norms or different perceived social risks in those settings.

In the case of international students – many of whom have been studying online at an Australian university from their home country during the pandemic – they may also inhabit different jurisdictions. As observed by the University of Sydney’s Tim Payne, this reality highlights how limited the terms of a student code may be as a basis for supporting and/or regulating expressive conduct. Topics that may be openly discussed without any sense of risk under Australian laws, and according to Australian campus or peer group norms, may be no-go zones in other cultural settings. In such cases, students may report that they self-censor for reasons that have nothing to do with what their lecturer says, or what their Australian classmates seem to think of the matter at hand. For these reasons, surveys that seek to map student experience with a few general questions – such as the IPA survey question on whether students sometimes feel unable to express their opinions at university – are unlikely to yield meaningful, reliable data. And where foreign students self-censor due to concerns that their view may provoke the authorities in their own country, there are real limits to what the university can do about this. In this circumstance, the institution’s duty of care for student well-being may entail not encouraging (or pressuring) them to speak their minds, where there are perhaps hidden risks in doing so.

As noted, social media participation permeates everything and often dissolves the campus learning context around any particular exchange of views. For students (and scholars) the fact that on-campus and off-campus contexts often overlap means that the perceived risks in one domain may shape their sense of risk in the other. In the US a FIRE survey of 20,000 students in 2020 (reported here) found that students were least comfortable with the prospect of expressing an unpopular view on social media (see Chart 10). The issue is to what extent the impulse to self-censor in that arena will translate into greater viewpoint conformity on campus (whatever their private view might be).

We need universities to “enlighten up” (6) Helping students build resilience

In their 2021 book Open Minds, legal scholars Carolyn Evans and Adrienne Stone consider a Canadian statement on freedom of speech from the University of Toronto. It promotes free exchange as mission-critical; but adds that the purpose of the university also depends upon an environment of tolerance and mutual respect … free from discrimination and harassment. Evans and Stone concur, arguing that freedom of speech is highly valued, but if members of the university are not treated as equals and cannot enjoy an environment in which they are able to participate fully, freedom of speech rings hollow…

Again, this can be a very complex balancing act. To hypothesise, a radically inclusive university community, firmly committed to academic freedom and intellectual integrity, should help its students learn skills and resilience by adopting (say) a hard heads, soft hearts approach to open-minded engagement with the issues at hand. That is, it will promote informed and robust debate; ensure respect for the lawful rights of others; allow diverse points of view to be voiced openly; and also prioritise tolerance on campus for diverse identities as well as diverse views, to help prevent silencing or shaming.

(In a multi-cultural, multi-faith society such as Australia, two-way tolerance has to be highlighted as a core value. To repeat Voltaire’s maxim: If you want us to tolerate your doctrine here, start by being neither intolerant, nor intolerable.)

In sum, social inclusion aids learning, as well as intellectual challenge. At a 2018 forum on academic freedom and freedom of expression on Australian campuses, law professor Adrienne Stone pointed out that for some students, learning resilience on campus may be hard work and may take time: It is simply not fair to expect a student from, say, a disadvantaged background in a minority religion or race in their first term of their first year … to be in a position to withstand the kinds of hurly-burly and robustness of debate that I might, for example, ask of a third year law student. And I think that we ought to be a little bit more conscious and explicit about the way in which we differentiate these contexts and the way in which we build students up … we actually want to produce really quite courageous, resilient, civic participants. But that might be the end point and not the assumed starting point...

A US example of this kind of socially inclusive resilience work is the Bridging the Gap program already mentioned. It takes groups of students from liberal and conservative colleges and teaches them to listen to and learn from each other, then asks them to consider how best to solve complex social problems from diverse viewpoints. BTG program leaders invite students to participate on the basis of 4 principles:

1. Our intention is to take seriously the things that others hold dear. If it matters to you then it will matter to me 2. We are not here to convince anyone they are wrong or try to change them 3. We are curious as to why others think the way we do, and rather than fearing we are diminished by listening carefully to ideas we might disagree with, we trust that we are enhanced by it 4. We believe there is more common ground and experience than we can anticipate, and when there is not, we can fundamentally disagree with someone and still respect, even love, them.

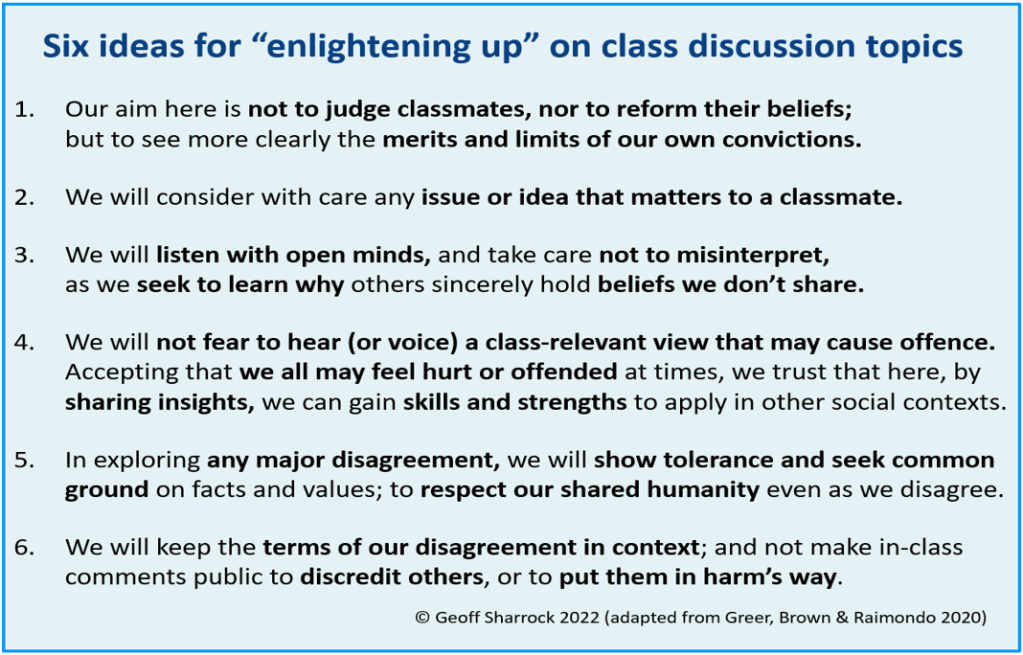

At the University of Melbourne, some scholars have adapted these principles, as a set of commitments to guide classroom or syndicate group discussions. The principles include being curious, charitable and willing to hear opposing views. (The guidance for Heterodox Academy discussion groups has similar messages: We value constructive disagreement, intellectual humility, intellectual curiosity, perspective taking, empathy, and empiricism. We want to get good thinking done – together.) At the Australian Catholic University, ethics professor Hayden Ramsay has devised a 10-point list of rules of engagement to promote respectful discussions in scholarly arenas – with a focus on debate quality as well as civility. These consider how participants may ascribe different meanings to key terms, prioritise values differently, rely on emotive language or unreliable evidence to persuade, or doubt the sincerity of those who disagree.

At Chart 11 (now updated more than once in light of reader comments) I’ve drawn on these ideas to formulate an “enlightening up” framework for (serious) class or syndicate group discussions. This is line with the two main premises of this project: John Stuart Mill’s 1859 insight that often, conflicting doctrines share the truth between them; and Bertrand Russell’s 1959 message that, in an ever more closely connected world, charity and tolerance are vital. The framework calls for careful consideration of others’ concerns, tolerance when there is major disagreement, and resilience to contend with issues or viewpoints that cause offence, on and off campus. Recalling the social media risks outlined earlier, tolerance here includes refraining from sharing a comment out of context to discredit an opponent’s standpoint; or worse, disclosing something private that might put a vulnerable person at risk of harm in some off-campus context.

Brief statements like these, highlighting the soft hearts aspects of shared inquiry in a group setting, and explicitly open-minded modes of disagreement, should not be too hard to introduce to a class. They offer some simple points of reference for when group discussions are likely to slide into conflict (such as the principle of charity that underpins Point 3 in line with Bertrand Russell’s message to future generations). Point 4 on the list is aimed at one important outcome of higher learning – graduate resilience (and agency) to contend with the kinds of intolerance that some will encounter off-campus. As University of Melbourne political scientist Tim Lynch put it (quoted in a recent transgender controversy story in The Age): The whole tenor of university life now – I think inherited from the US – is creating an environment of almost complete safety, where you’re not discomforted or obliged to deal with opposing views … Our role as academics is to create a climate in which disagreement is not lethal. That’s how you build robust citizens. And I think that possibly as a sector we’re failing in that regard.

If used widely across courses and cohorts, a shorthand statement along Chart 11 lines may help to inform the wider campus norms envisaged by more formal institutional rules. Typically, student codes and staff codes offer detailed guidance on the complex balances that institutions must strike between free and open exchange across viewpoints, restrictions on unlawful speech, and duties of care for student and staff well-being that rule out other forms of unacceptable conduct. But (as some have observed in this project) student codes are rarely read, much less studied closely. For all its legal and conceptual clarity, for students the French Model Code is not a gripping read. Despite its formal adoption, quotes from the Code are unlikely to appear on campus on (say) student T-shirts.

Turning to the hard heads aspects of higher learning, here the focus is on promoting critical thinking and robust debate, with clear-headed reasoning and hard evidence – however inconvenient the resulting conclusions may be. To promote higher standards of argument on complex topics, scholars must learn to recognise rhetorical tactics such as red herring or straw man arguments, and ad hominem attacks aimed at discrediting an opponent personally, rather than refuting their claims.

Chart 12 presents another “enlightening up” approach (as Immanuel Kant put it in 1784, the motto of Enlightenment is “dare to know!”). This focuses on scholarly counter-argument to refute a specific claim or general case. (While the French Model Code offers what we might call heretic protection to scholars with unpopular views, academic freedom also should ensure that their views will be scrutinised and open to challenge.)

Scholars usually seek to contest an opponent’s claims with logic and evidence, a level 2 counter-argument. If both parties do this well enough for long enough, the case at hand — whether mainstream or minority — may be refuted (or reframed or reaffirmed) at level 1.

But, as the list of tactical avoidance items at level 3 suggests, there are many ways to differ without resolving anything in any way at all. Here the first 2 appeal tactics enlist support for a view by appealing to a higher authority or greater good. (But how far do we rely on one, or prioritise the other?) The next 4 avoidance tactics sidestep or misread the point of an opponent’s view, by raising adjacent considerations, or by discounting the other’s grasp of the issues. (But how relevant and/or reliable are these claims?)

At level 4 the final 3 exclusion tactics withdraw commitment to engage seriously with an opponent’s viewpoint, by casting doubt on their morality, sincerity or credibility. At this point the prospect of further good faith discussion of the issues is remote. Those on the receiving end are in effect being cancelled.

As the Ridd case illustrates, a level 4 tactic in a university context may be to take offence at the tone or terminology of a critique (BadHom 1). In an institutional context or open forum this kind of objection may appear more civil than simply accusing your opponent of bad faith, or denouncing them as an FBDZS (fool, bigot, denier, zealot, snowflake – BadHom 3). But the chilling effect of taking offence too readily or too routinely may be similar. By shifting off-topic to invoke (presumptive) rules of civility, an offence allegation offers scope to censor an opponent’s statement on the basis of some unintended inference; or to end the discussion prematurely while claiming higher moral ground. At the very least, ruling an opponent’s point out of bounds – like a tennis player assuming the role of umpire – may end the exchange, and leave the parties at loggerheads. That is (as Duncan Maskell put it), throwing metaphorical bricks at each other with their substantive points of genuine disagreement left unexamined.

Responses such as these are described by one participant in this project (Griffith University philosopher Hugh Breakey) as meta-argument allegations of moral wrongdoing. These, he argues, can derail discussions about important topics … license efforts to silence, punish and deter … escalate conflicts, block open-mindedness, and discourage constructive dialogues … (and) exert a damaging influence on public deliberation and political discourse.

With scholarly debates the aspiration with Chart 12 will be (as Michelle Obama put it in a political campaign context): When they go low, we go high. Recalling the re-coding of everyday language on social media, and concerns about harmful speech in UK and US student data, an inescapable dilemma with any policy framework in this area will be that common terms such as respect or harm or free speech – or indeed cancel culture – are open to definitional drift or concept creep. This issue came up at Cambridge University in 2020, when scholars opposed a new policy what would have made respect for others’ opinions mandatory. In the end the university opted for tolerance instead. The debate recalled Cambridge philosopher Simon Blackburn’s 2004 critique of the idea of respect in matters of religion: ‘Respect’, of course is a tricky term … The word seems to span a spectrum from simply not interfering … right up to reverence and deference. This makes it uniquely well-placed for ideological purposes. People may start out by insisting on respect in the minimal sense … But then what we might call respect creep sets in … In the limit, unless you let me take over your mind and your life, you are not showing proper respect for my religious or ideological convictions.

In recent Australian debates about transgender communities on campuses, the same kind of issue arises, with terms such as harm or hate. As Sydney and Deakin University scholars Luara Ferracioli, Matthew Lister and Sam Shpall argued recently: causing distress, hurt feelings or discomfort in students cannot be sufficient on its own to limit academic speech. While these are real concerns that universities must always take seriously, they also offer activists scope to make hate speech allegations, that to libertarians seem exaggerated. The issue arises in sex and gender debates on campus. Reporting in The Age on the University of Melbourne controversy, journalist James Button put it this way: Are there forms of speech, beyond those that the law says incite violence or hatred, that should be restricted if they are deemed to cause harm? If so, who defines that harm?

Recent research in social psychology by Nick Haslam et al maps a complex mix of social implications arising from concept creep and harm inflation. For universities it may not be possible to draw clear and simple policy lines that can address such cases. For some students (and some staff), wider social narratives on such topics may entail real risks of social harm – not on campus directly, but in other contexts. (As a Melbourne colleague pointed out on the controversy reported in The Age: For most people, the issue of “cancel culture” is an abstract intellectual battle. For us, we are in an actual real battle with actual real consequences to our actual real lives…)

Meanwhile, several participants interviewed for this project were concerned about the rise of harm allegations in university contexts. Andrew Norton put it this way: I think what’s happening with this harm culture is people saying that any attack on a view that I hold dearly is an attack on me, and I’m going to respond accordingly. I think we need to step back from that and say that ideas and people are separate. If you take all disagreement as a personal assault then it is hard to have a discussion. Academia is really about saying “It’s not about you it’s about the ideas, independent of your background or how passionately you hold a view – all of that is irrelevant for this narrow purpose”…

Hugh Breakey put it this way: I’m sure that there are academics that manage to create a context when they’re in their own classrooms where everyone feels very safe, where people can experiment with different ideas and where everyone can feel like this is part of the intellectual journey they’re all going on. But I’m not sure that there’s enough work done on what their techniques are for us to teach this in a way that’s transferable, that is communicable, and that is able to be done at scale. We need to get students to learn that it shouldn’t be an issue when people are disagreeing with one another. I think it is something that is becoming newly important for us now, in a way that it wasn’t a decade ago and certainly two decades ago.

As the French Review notes, campus rules requiring respect can be applied too widely (by staff or by students). On the same logic it argues that diversity and inclusion policies should be conservative in their application to expressive conduct. Again, the Ridd case debate is instructive. Disputing a court finding in Ridd’s favour, one supporter of his sacking argued in The Australian that, since Ridd’s incivility had been dubbed denigration, it should not have been protected by JCU’s academic freedom policy. Why? Because to denigrate is to vilify. The trouble with this kind of rhetorical tactic – adding a dash of concept creep to bolster the impression of serious harm – is that a complainant could as readily claim that to denigrate is to defame. But in the case at hand, neither accusation would stand up in court.

As one participant in this project (law professor George Williams of the University of New South Wales) wrote of the Ridd case in 2021: the ability of academics to publicly debate and question the quality of research should not be in doubt. We should also not expect that academics will always act politely and within civilised bounds. In the pursuit of truth, heated and sometimes intemperate debate is to be expected. Academics and universities need to be tolerant of sharp criticism and avoid the temptation to shut down debate.

In their 2021 book Open Minds, law professors Carolyn Evans and Adrienne Stone concur (Chart 13).

We need universities to “enlighten up” (7) Resisting cancel culture in academic work

Respect rules can be invoked to empower the intolerant. To put it starkly: tyrants, zealots, bullies and narcissists all demand respect for their opinions, however misguided. In the context of a scholarly forum or a student seminar, we’re now a long way from the Chart 11 vision of higher learning, with its studiously open-minded exchanges. Whatever form Chart 12 level 4 tactics take, as exclusionary cancel culture tactics they are at odds with the promotion of constructive engagement on difficult topics, and the tolerance for diverse viewpoints, that universities routinely highlight in their policy statements and brand identities as sites of open-minded but also rigorous inquiry.

In his recent essay on The making of a cancel culture one project participant (University of Newcastle philosopher Russell Blackford) considers a number of cases where scholars have got into trouble (such as Bertrand Russell, who – like Socrates – was accused (in 1940) of entertaining immoral ideas that would corrupt the youth). He concludes: Cancel culture … is unhealthy for democracy and for academic life. The upshot is that decent, smart, thoughtful people are self-censoring, expressing their real views on many topics only within close and trusted circles … what J.S. Mill called, in On Liberty, “the sacrifice of the entire moral courage of the human mind.”

As another project participant at the June webinar remarked (professor Alan Davison from the University of Technology Sydney) in university contexts cancel culture is multi-faceted – a multi-headed hydra. When faced with open-letter demands, negative media attention, or an internal complaint when a scholar’s viewpoint provokes some form of umbrage, what should university leaders do? In 2020 one vice-chancellor (Greg Craven at the Australian Catholic University) presented the issue and his own response this way: Most months, someone demands I sack an academic for writing something outrageous. Almost invariably, if they had just as pungently written the precise opposite, I would have a letter of commendation. I usually suggest the complainant publish their own rebuttal…

This suggests that the principle of academic freedom can be invoked as readily to protect institutional leaders from public or intramural pressure to censor, as by scholars who find themselves being targeted or sanctioned for their allegedly unacceptable views. As Andrew Norton observes: university reputations are partly protected by the perception that academics personally have academic freedom. They speak for themselves, not for their colleagues or the university as a whole.

In cases of public controversy, a university need not take any public position on whether a scholar’s lawful critique or expert viewpoint is intellectually justifiable. If it has a relevant policy position to declare, the university may do so while also making clear that this implies no administrative pressure on the scholar to subscribe to the assumptions on which it is based. And if scholars take offence at one of their own professing to expose their errors, this is best addressed in the institution’s academic domain – perhaps in a staff or student forum – rather than in its administrative domain.

This reflects the old idea of the university (as John Henry Newman put it in 1852) as a safe place for the collision of mind with mind and knowledge with knowledge. And Immanuel Kant’s dare to know! motto for the Enlightenment project in 1784, which calls for social institutions to accommodate dissent by allowing scholars to be free to use reason publicly in all matters.

In cases where attempts to adjudicate a case in the administrative domain may consume a good deal of management time, and where the process or outcome may attract adverse media attention, why not use an academic forum instead? As a way of airing the issues this may be a far cleaner and simpler approach, with less cost to the parties, and less reputational risk to the institution if the matter is mishandled. Again, the Ridd case offers a cautionary example. In her account in The Guardian, commentator Gay Alcorn suggested the academic path as the better approach: For all the university’s sensitivity about its brand and reputation, you have to wonder if it has damaged its own standing with its strident calls for “collegiality” and its repeated insistence that Ridd stay mute. The other way would be for academics not to complain about Ridd’s impolite turn of phrase, but to reject his arguments, loudly and with evidence … And for the university to put up with their troublesome academic and to not be obsessed with process and its own self importance…

On this view a sensible and practical step towards instituting an enlighten up culture on campus is for all scholars to commit to allowing each other to discuss any problem that presents itself (as the Chicago Principles put it). Within the law – and with scope to make rare exceptions for reasons that can be explained readily as a matter of good policy, if made public – the default setting should be that no question relevant to the topic of the day may be rendered undiscussable by scholars.

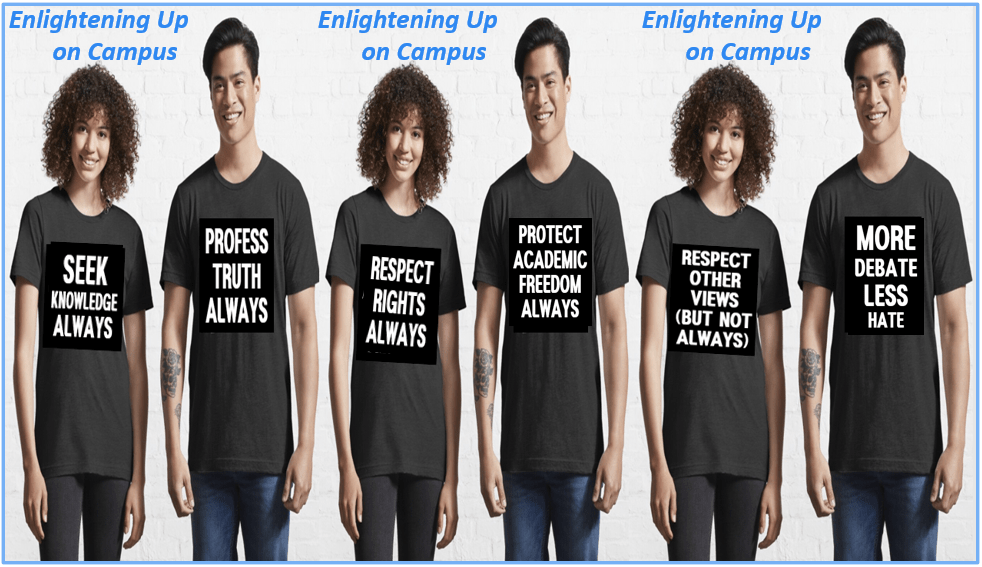

In sum: campus cultures must accommodate the fact that in Australian universities, scholarly dissensus often (and necessarily) runs deep. In practice, what does it take to seek and share and strengthen truth and knowledge reliably? Put simply: if the aim is to SEEK KNOWLEDGE ALWAYS, they must urge scholars to PROFESS TRUTH ALWAYS. But, since speaking truth to power poses risks, they have a duty of care to scholars, to PROTECT ACADEMIC FREEDOM ALWAYS. But, since unlimited free expression may harm others, they must also urge scholars to RESPECT RIGHTS ALWAYS. But, since the idea of respect is open to concept creep, campus cultures must also uphold the right to disrespect (and better yet, to debunk) fallacy, delusion and dogma. As a call for civility on campus, respect is a laudable norm which (when minds collide and viewpoints clash) may also be a risible rule to enforce. Tolerance underpins the radically inclusive university, not the enforcement of respect as such: RESPECT (BUT NOT ALWAYS).

In a university system such as Australia’s with 1.5 million students from a wide range of backgrounds (1 in 4 are international students) this is the challenge and the promise of a radically inclusive approach to higher learning. With practice in the disciplines of tolerance on campus, freedom from hate (and from harmful speech that violates rights) could be promoted by way of more debate, not less. Faced with calls to sanction a scholar for professing an unpopular view, the response from institutional leaders should be informed by all the considerations at Chart 14, including MORE DEBATE, LESS HATE.

Again, the procedural implication of this seems clear. On-campus campaigns/complaints by colleagues or students about the content of a scholar’s viewpoint should be referred in the first instance to an academic discussion forum – ideally with another scholar presenting a counterpoint if there is widespread concern. As one project participant put it (University of Queensland educational psychology professor Jason Lodge): some of my fondest memories of the entire time I’ve been in academia, are where there have been really conflicting viewpoints … getting those people in a room together and then just seeing how it plays out has been amazing. It was great as somebody who was coming through to see these heavyweights who have very different views – not so much ideologies they are probably really ontologies – come together and nut these things out and find some common ground…

Depending on the circumstances, in a large campus forum students may be invited to form a panel or two (with say, activists on one panel, libertarians on the other), to assess and comment on the quality of the arguments put forward, against a Chart 12-type outline of good and bad ways to disagree. This would highlight the enlightenment premise that (as Heterodox Academy puts it) great minds don’t always think alike. Whatever the outcome of the substantive debate, such a process is likely to be more edifying than weeks or months spent awaiting the result of an administrative complaint-handling process, behind closed doors.

An interview participant with experience in this area supported the idea in these terms: I think putting it back into the open forum of debate is always good – I think the great exemplar of that is the final scene of the Oresteia, where Orestes is hounded by the Furies into the forum of Athens and Athena comes to say we’ll deal with it … by way of an open court process. That is a model for how you resolve claim and counter-claim, offense and counter-offense…

To reinforce this as a campus norm is likely to require more visible leadership. In a recent interview about the effects of social media in US universities, Jonathan Haidt – himself a political centrist who supports classical liberalism – argued that institutional leaders found this difficult: People on the centre-left who are really the ones who run the institutions are so intimidated … they can’t stand up to being called racist or sexist or transphobic… I’ve spoken to a number of university presidents, none of them are woke, they’re almost all true liberals, but they’re terrified…

In the course of this project, some participants echoed this concern in the Australian sector. With social media dynamics routinely erasing context and nuance, the communication challenge will be to widen the parameters for what may be safely debated on campus. In voicing these concerns, none argued for what Evans and Stone call free speech absolutism. Nor did any suggest that academic freedom should somehow protect otherwise unlawful speech. As one interview participant put it: the idea of a campus where everyone says anything that comes into their head is a hideous idea.

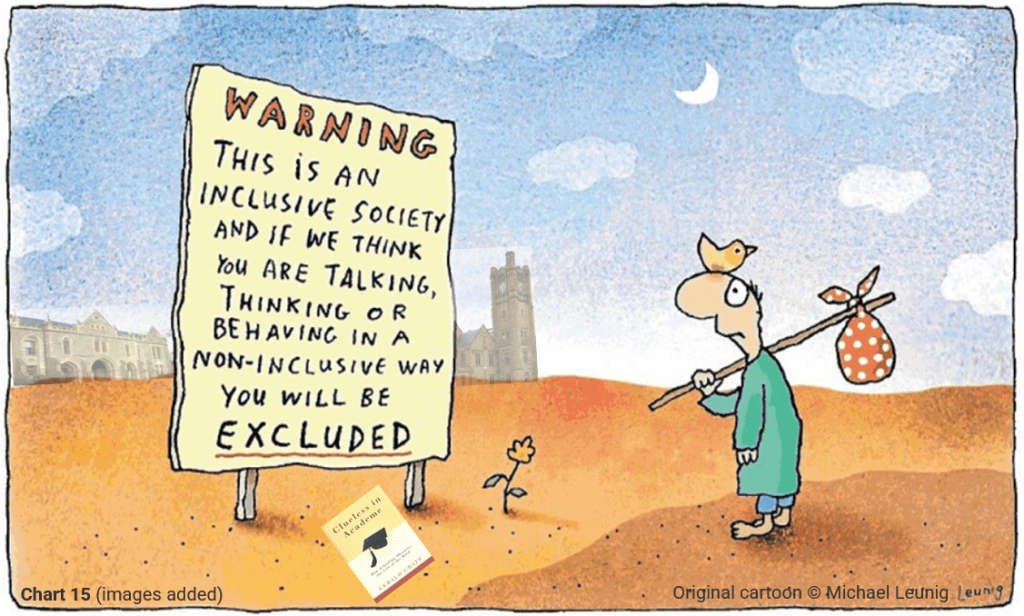

In sum, a radically inclusive university would find ways to promote what US scholar bell hooks called “radical openness“. And in promoting the disciplined practice of tolerance as a paramount value in a multi-cultural, multi-faith society, scholars and administrators would take care not to enact the tolerance paradox Karl Popper outlined in The Open Society and its Enemies in 1945: If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them. To illustrate this point, the whimsical Australian cartoon at Chart 15 represents the risk campus newcomers may feel, and their sense that they may be misconstrued and expelled not for expressing hatred or discrimination or intolerance toward others, but for being (as US scholar Gerald Graff put it two decades ago) clueless in academe.

The idea of a radically inclusive university is not entirely new. In his Robert Menzies Oration in Melbourne in 2018, University of Birmingham vice-chancellor David Eastwood characterised the university in its proper role as just such a community of knowledge and critically, as a safeguard against the corrosive effects of social media outlined earlier: There is a danger … that these new forms of communication construct the very antithesis of a university…(with) two important consequences. The first is the risk of a corrosion and coarsening of public debate. That is, the creation of the world of mutually-reinforced assertion, sometimes founded on misapprehension and misunderstanding, and sometimes founded on wilful misrepresentation. A second challenge is to the idea of the university itself. Universities are far from immune from wider social forces. To be a university, an institution must remain open, must remain a place of debate, and must ground all that we do in those disciplinary conventions which enable us to establish truths, (and) challenge concepts and beliefs. Let me, then, rally to the defence of the idea of the university at a time when knowledge is not so much being democratised as corroded…

When we glance back at the lives of long-dead scholars referenced in this paper (what some might call a dead white males society) we see that many were sanctioned for professing some valid truth or viewpoint too inconvenient to be aired, according to the politics of their social setting at that historical moment. And if they were alive today, most would themselves now need to “enlighten up” on topics where, as creatures of their time, some held views now generally accepted as unfair and inhumane (such as racism). Persecuted or not, all would concur with Kant that for the scholarly profession to play its part in human progress, intellectual freedom must be protected. Universities have real duties of care in this area; not least when a scholarly project (such as this one) prompts university management-level or collegial ostracism.

This can arise from a perceived lack of moral legitimacy, or from a potential institutional brand risk. Or (as per Chart 15) to both. With cultural institutions in liberal democracies (not just universities), a sign of moral panic is when sensible, capable senior people appear to endorse Orwellian forms of intolerance within their own institution, in the name of respect or inclusion. Amid critiques that our university leaders are themselves mostly “white, male and grey” and their institutions thus subject to Western forms of groupthink despite visibly diverse campus communities, leadership legitimacy itself may seem at risk when a controversy gains media attention and threatens the brand.

How best to promote the radically inclusive university? There are some simple things we can do. For example, provide students with simple (but not too simple) frameworks for free expression and constructive disagreement within lawful limits and in line with the university’s higher learning mission. With clearer guidance on campus rules (not to be confused with social norms), we can refer internal disputes and controversies to the academic domain wherever possible, to keep the substantive questions discussable. Turning to more complex questions, we can seek better, more comprehensive data on viewpoint discussability among students and staff, to put concerns about (so-called) free speech crises and self-censorship crises, and cancel culture cases, in context. And suggest ways to promote greater viewpoint visibility on our university campuses, where intellectual pluralism is accepted and protected as an inescapable feature of the practice of rigorous and open-minded scholarly inquiry.

Even with clearer policy, better procedures and better data on free expression issues, a campus culture that consistently supports an enlighten up vision for society is unlikely without visible and vocal leadership; not as a ritual declaration, but when it counts. The French Review concluded that any formal free expression policy could be undermined in practice, by institutional cultures that gave priority to other considerations. Perhaps in reply to those who had rejected any need for a Review, it observed that: The recitation of a generally expressed commitment to freedom of speech and academic freedom does not of itself provide strong evidence of the existence of such a culture.

As well, university leaders will always face endless competing demands to support one constituency or another. As former University of Melbourne vice-chancellor Glyn Davis and I wrote in a book chapter on university leadership: In an ideal world … It would be refreshing to discover that, given the value such institutions place on the dispassionate sifting of logic and evidence, scholarly communities had found ways to govern their affairs in more enlightened and exemplary ways than (say) business or government enterprises. Such an ideal approach, of course, would leave universities immune to office politics, palace intrigue, or factional antagonism. Yet, by most insider accounts, university leadership remains a risky business … Examples abound of university leaders caught in the cross-fire between the demands of student activists, the grievances of faculty members, the sensitivities of government authorities and corporate sponsors, and public displays of wrangling among colleagues in the media. In this sense it is never lonely at the top in a university, and Machiavelli’s advice remains ever relevant…

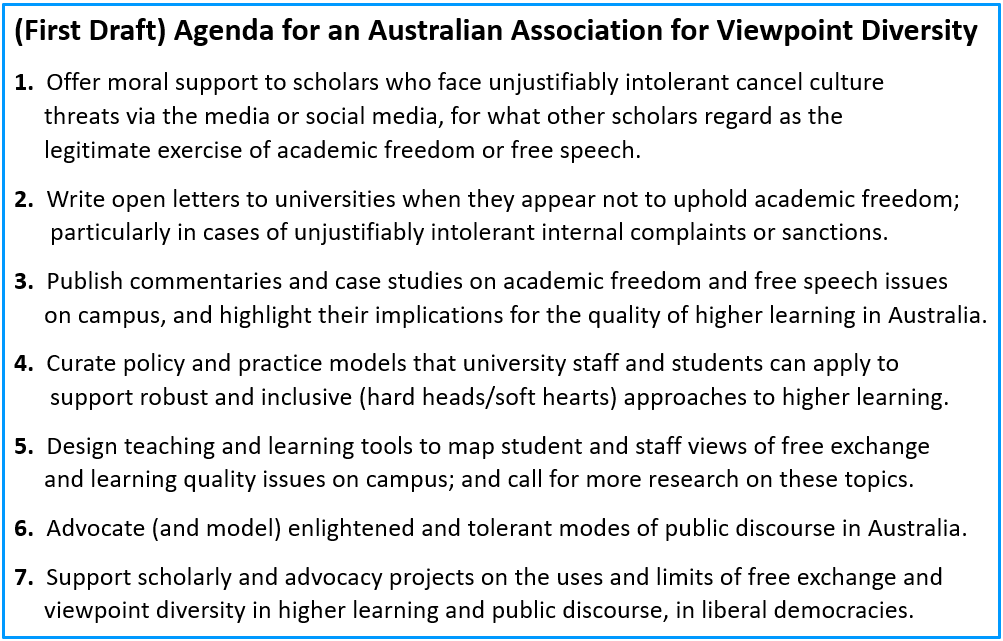

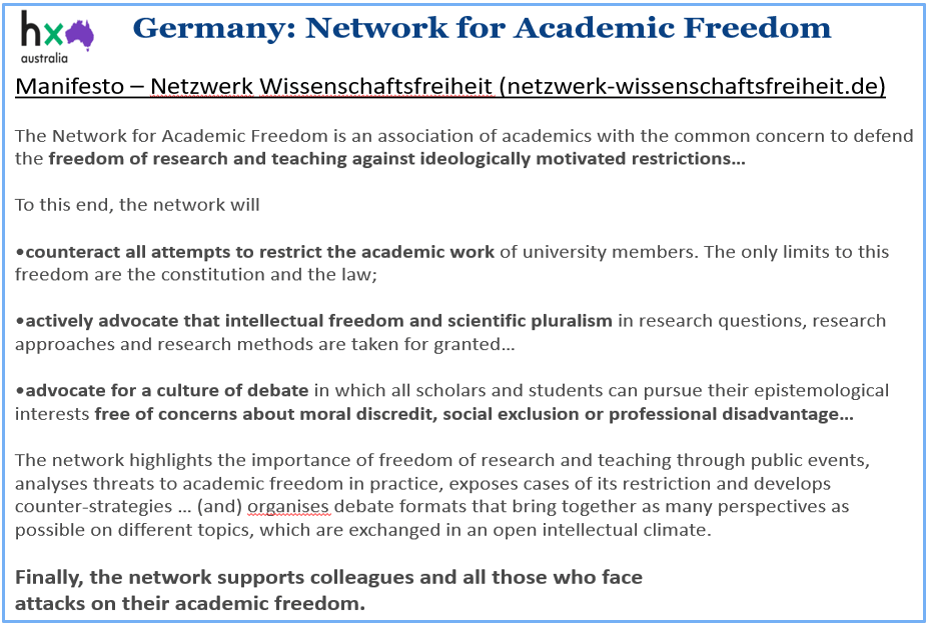

Next steps: do we need an Association for Viewpoint Diversity?

At the outset, a premise of this project was that it would lead to a new Association devoted to further work on these issues. This would be philosophically aligned with Heterodox Academy and share its main aim: to improve the quality of research and education in universities by increasing open inquiry, viewpoint diversity, and constructive disagreement. However, as outlined at the May webinar (by Andrew Glover at RMIT University, who initiated this project with the Association idea in mind) the new body would operate quite separately, to focus on the Australian higher education context and take public positions on Australian cases as they arose.

Participant views on this proposition were mixed. They included concerns about the political positioning of the term viewpoint diversity. For some audiences the term meant recognising intellectual pluralism in scholarly inquiry; for others it was code for opposing diversity and inclusion policies that imposed (unduly restrictive?) administrative constraints on free expression on campuses. So, a vocal advocate of viewpoint diversity might be welcomed in one department tea-room as a defender of academic freedom against corporate-managerial encroachment on the rights and working conditions of scholars; and yet be shunned in another as a reactionary engaged in some kind of right-wing dog-whistling political project.

At the May webinar some suggested we consider various overseas models; or speak first with other Australian academic organisations that at times raise concerns about how cases that touch on academic freedom rights are being handled. We learned of an NTEU proposal that universities have an academic committee consider internal complaints that might conflict with academic freedom before any administrative process commenced that handed the matter to HR. This raised other issues. What kinds of cases are best handled internally by the institution, such that an external body taking public positions on cases at hand might make internal resolution more difficult? And if an Association found itself focussing on particular kinds of cases, would it be labelled as yet another culture-war group, not focused on academic freedom, constructive disagreement, etc. as such, but inclined to pursue cases that aligned with its own political agenda?