Good Riddance? Or Bad Judgment? The Peter Ridd versus James Cook University saga has been examined in two courts so far, in 2019 and 2020.

Ridd’s sea of troubles arose from complaints by another JCU professor (coral research centre director Terry Hughes) about his criticisms of Great Barrier Reef research. He was sanctioned in 2016 and 2017 for what JCU deemed “uncollegial” and “disrespectful” conduct; and dismissed in 2018 for a “pattern of misconduct” (including his refusal to keep JCU’s sanctions confidential, as directed).

By then Professor Ridd had taken legal action to defend what he saw as his “intellectual freedom”. In 2019 a Federal Circuit Court judge ruled against all of JCU’s sanctions. JCU appealed. In 2020 the full Federal Court majority overturned the 2019 ruling (a third judge dissented in favour of a Circuit Court re-run). Ridd now aims to appeal to the High Court.

The 2019 court ruling had its flaws. But the 2020 ruling is flawed also; it should be reviewed. (Update, 11 February 2021: the appeal will proceed later in 2021).

Meanwhile, last year’s French Review findings, on risks to academic freedom in the wider sector, shed light on the policy dilemmas at play in the Ridd case. Here I will argue that, in its mishandling of complaints about Ridd airing his views on Reef science, JCU tossed any meaningful concept of academic freedom overboard – despite its insistence to the contrary.

As a Guardian journalist outlined in 2018, Ridd got into hot water in 2016 for using terms such as “misleading”: “the university had got hold of an email that Ridd sent to a … journalist to look into work Ridd had had done suggesting that photographs released by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority indicating a big decline in reef health over time were misleading. Ridd couldn’t help a dig: The photographs are ‘a dramatic example of how scientific organisations are quite happy to spin a story for their own purposes’. The authority, and the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies – based at James Cook University – ‘should check their facts before they spin their story … (if asked) my guess is that they will both wiggle and squirm because they actually know that these pictures are likely to be telling a misleading story…'”

JCU formally censured Ridd for failing to “respect” others’ reputations; and did so again in 2017, after Ridd said in a TV interview that he didn’t “trust” the work of Reef science institutes. The ensuing wrangle highlights issues raised in last year’s French Review. It found no “free speech crisis” in Australian universities. But, nor did it confirm the sector’s view that free speech was “alive and well”. In particular, it found problems with policies couched in vague language. For example:

The terms ‘lack of respect’ … and ‘reprehensible’ are wide … it does not require much imagination to apply them to a considerable range of expressive conduct … That kind of terminology … is rife on university campuses in Australia. It makes the sector an easy target for those who would argue that the potential exists for restrictive approaches to the expression of … opinions which some may find offensive or insulting.

Report of the Independent Review of Freedom of Speech in Australian Higher Education Providers (French Review), March 2019

The Review didn’t support calls for a sector-wide imposition of the University of Chicago principles. Instead it drafted a Model Code for universities to adapt and adopt. (A review of their progress by former Deakin University vice-chancellor Sally Walker will report to the Education Minister later in 2020.) The Code may be read as a kind of “Heretic Protection Act” for viewpoint diversity. It sets up academic freedom as a “defining value” for universities. It rules out unlawful speech (such as defamation or racial discrimination). But, it expressly doesn’t extend to protecting everyone from being “offended or shocked or insulted by the lawful speech of another.” In this, it echoes the Chicago stance:

…although all members of the University community share in the responsibility for maintaining a climate of mutual respect, concerns about civility and mutual respect can never be used as a justification for closing off discussion of ideas, however offensive or disagreeable…

Report of the Committee on Freedom of Expression, University of Chicago, 2014

The French Review notes that academics and universities don’t have a typical employee-employer relationship: “Freedom of speech is an aspect of academic freedom … which, in this context, reflects the distinctive relationship of academic staff and universities, a relationship not able to be defined by reference to the ordinary law of employer and employee relationships. Academic freedom has a complex history and apparently no settled definition. It is nevertheless seen as a defining characteristic of universities …”

The promotion of free expression as central to academic work is part of the Western “Enlightenment” tradition. Here scholars may publicly question orthodoxy and “speak truth to power”. As “tribunals of truth”, universities support open inquiry by way of free exchange: the “collision of mind with mind, and knowledge with knowledge“.

Now, back to Ridd and JCU. In my (extremely inexpert) view, Ridd’s criticisms of Great Barrier Reef science seem largely (but not entirely) unjustified. His view is that Reef research is often unreliable and that its reporting often overstates the level of damage or risk; and that, despite Reef corals bleaching “every decade or so”, the system is so resilient that they can recover rapidly “in a decade or so”. He also believes that:

challenges to the conventional wisdom are typically ignored, largely drowned out and sidelined by the majority. There is now an industry that employs thousands of people whose job it is to ‘save the Great Barrier Reef ’… we can no longer rely on ‘the science’, or for that matter our major scientific institutions…

Peter Ridd, The Extraordinary Resilience of Great Barrier Reef Corals, and Problems with Policy Science, 2017

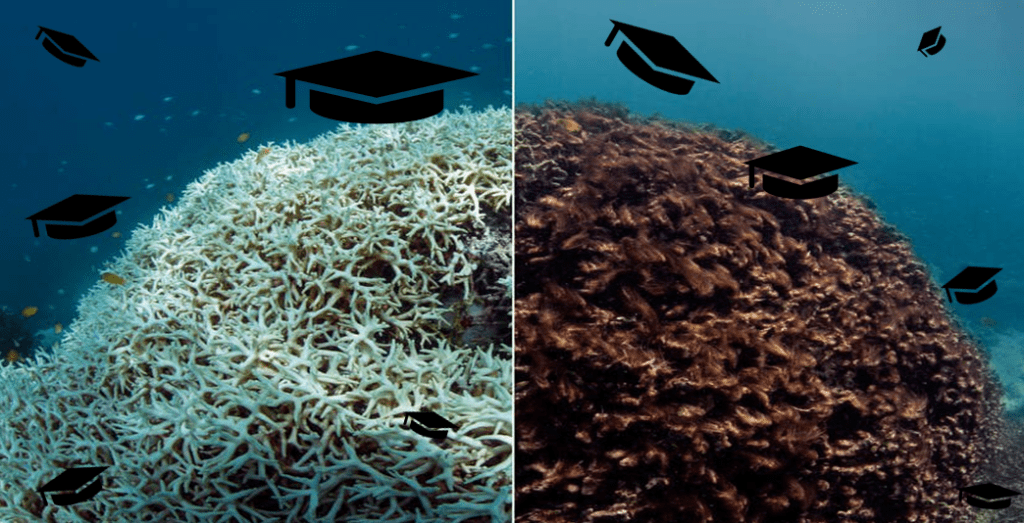

The view that research routinely overcooks these Reef risks now seems to have been sidelined by events. In April this year, JCU researchers reported the third mass bleaching event in five years, and the first on record with severe bleaching in all three GBR regions. An April 2020 media release from the ARC Centre for Excellence for Coral Reef Studies put it this way: “The first recorded mass bleaching event along the Great Barrier Reef occurred in 1998, then the hottest year on record. Four more mass bleaching events have occurred since—as more temperature records were broken—in 2002, 2016, 2017, and now in 2020. This year, February had the highest monthly temperatures ever recorded on the Great Barrier Reef since the Bureau of Meteorology’s sea surface temperature records began in 1900”.

On the question of unreliable research and calls for better quality assurance, in 2018 other researchers published rebuttals of several of Ridd’s (and his co-authors’) criticisms: “… their critiques demonstrate biases, misinterpretation, selective use of data and over-simplification, and also ignore previous responses to their already published claims.”

With alarmist media reporting, Ridd is on firmer ground. In June 2016 the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority itself expressed concern about “headlines stating that 93 per cent of the reef is practically dead … (and) reports that 35 per cent, or even 50 per cent, of the entire reef is now gone … (in fact) the overall mortality rate is 22 per cent …”

An irony here is that, days before Ridd was censured in 2016, another JCU researcher was raising concerns about “misleading” media headlines – such as “Half of Great Barrier Reef ‘dead or dying'” – based on his own Centre’s press release: “Most of the recent international coverage was based on a press release from the ARC Centre for Coral Reef Studies … (in fact) 45% of the reefs assessed had 30% or less bleaching. In the southern section, only 1% of reefs were … “severely bleached”… to state that “climate change has destroyed 93% of the Great Barrier Reef” is a misrepresentation … the more accurate way to frame the results … is to say that only 7% of the coral reefs … have completely avoided bleaching…”

This clarification makes sense. However, the press release was titled “Only 7 per cent of the Great Barrier Reef has avoided coral bleaching”; and it featured director Terry Hughes saying: “In the northern Great Barrier Reef, it’s like 10 cyclones have come ashore all at once“. When researchers use such analogies, it’s unsurprising if sympathetic journalists equate their account of bleaching with “devastation” or the “smashing” of half the Reef.

The science communication problem reflects how numbers, percentages and inexact terms slip out of context in media reporting. As GBR Marine Park Authority Chief Scientist David Wachenfeld stressed in a recent Senate hearing, “single percentage statistics will always struggle to accurately depict what’s going on”. Meanwhile, since bad news begets big-bang headlines, Reef reporting in recent years seems to have run roughly like this:

“MASS BLEACHING OF VERY LARGE PARTS of (parts of) the Reef region has affected many individual reefs (at least in part). Of these, many reef corals are BLEACHED SEVERELY, OF WHICH MANY WILL DIE (as others recover from mild or moderate bleaching). HUNDREDS OF REEFS HAVE BEEN AFFECTED (of the 3000 across the Reef region).”

As well, Reef researchers know that “photographs speak louder than words”. The visible effects of climate change offer scope for “symbiosis” between funding-hungry researchers (lending expert authority) and headline-hungry journalists (lending wide exposure). If accused of hyperbole, each may say: “that was just taken out of context”.

Ridd wasn’t censured for criticising media hype, but what he sees as poor research quality and reporting standards. Yet even here, his critics can’t dismiss his concerns entirely. A study published in Nature in 2020 found several GBR research papers to be unreliable, as another group of researchers (Ridd not among them) couldn’t replicate the findings. (Update, 21 October: GBR researchers have published a detailed rebuttal in Nature, to which their critics have replied). The discovery at a Swedish university that a researcher had fabricated data led to concerns about her earlier PhD research at JCU, and questions about a “collage” suggesting 50 lionfish were used in a published study, far more than JCU records indicated.

To Ridd’s supporters, such cases validate his criticisms of poor Reef research quality. However, apparent misconduct may not be proven so. JCU convened an independent panel, releasing its finding in August 2020 that there were “no grounds for a finding of research misconduct”. But the Panel’s specific findings were less reassuring: “Not to state that animals were re-used and not to give the actual numbers is extremely misleading and should not happen. It is, nevertheless, the case that, in some fields, people have chosen not to care about it and it is also the case that the two papers we examined in detail were refereed by reputable journals … the two lionfish papers … present problems in accurately determining the number of fish used, and/or re-used in the experiments … One would expect thesis examiners and paper reviewers to have picked up on the question of numbers and usage of lionfish … but this does not appear to have happened … inadequate reporting of data has been identified in a number of papers, but the Panel considers that this reflects on professional standards rather than misconduct…”

(Update, 9 May 2021: further GBR research papers on fish behaviour have been found unreliable due to replication and data integrity problems. JCU and the authors concerned have dismissed the report.)

Cases like these support Ridd’s concerns and his “quality assurance activism”. What irks critics is his habit of claiming systemic bias. Ridd’s own history of hyperbole hardly helps his case. In a 2007 opinion piece titled the “Great Great Barrier Reef Swindle” Ridd riffed on the polemic, “The Great Global Warming Swindle”. This led to detailed exchanges with researcher Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, who took issue with the term “swindle”.

(In the fraught politics of climate science, disparagement flows both ways. In 2010 Hoegh-Guldberg labelled Ridd a “denialist”, who sought to “deliberately confuse” the public with “misleading claims”. In 2019 a panel chaired by a former Chief Scientist reportedly accused Ridd of “misrepresenting” science on behalf of industry interests. Such crossfire among scientists could benefit by considering longstanding debates in social science about “policy-based evidence“.)

With this context in mind, having sided with his opponents on the general credibility of Reef science, let me now side with Ridd on academic freedom. The complaints about Ridd, and JCU’s handling of them, were also largely (but not entirely) unjustified. The French Review notes that in universities, other priorities often risk the “erosion” of free expression. To counter this, its Model Code provides that its own framing of rights and restrictions “prevails, to the extent of any inconsistency, over any non-statutory policy or rules of the university”. Had the French Code been in place at JCU, its scholars could not presume that administrative rules will protect them from being “offended or shocked or insulted”.

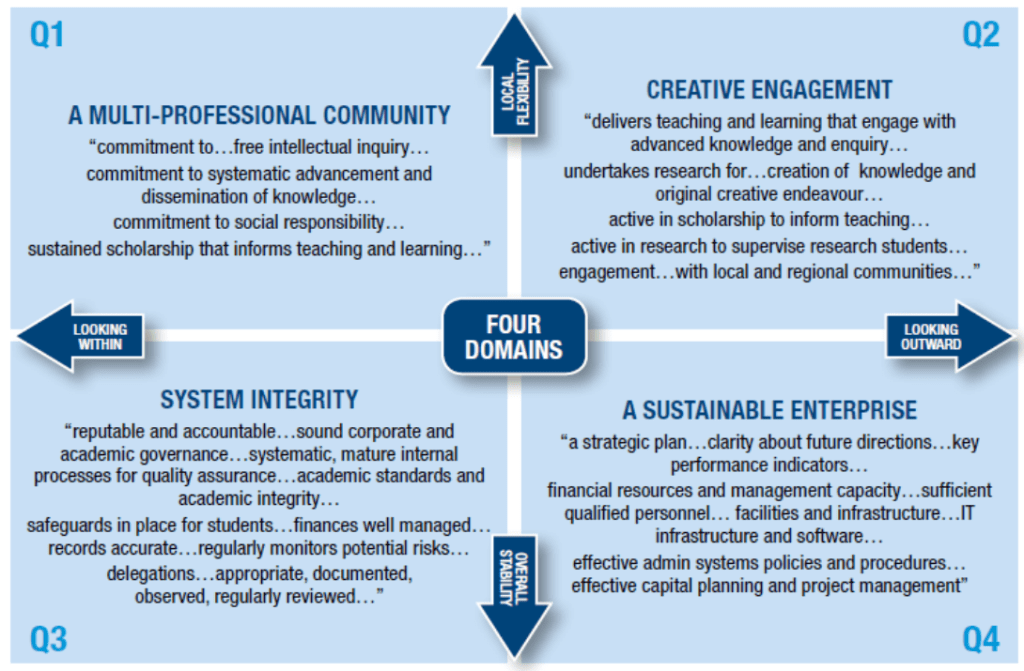

In turn, concerns about lawful but “disrespectful” criticism would have to be resolved differently. For example, Ridd’s critics could be advised to take up his challenge in the August 2017 interview (which led to another complaint and censure) to “have a debate for a couple of hours, and thrash this out”. This would refer the substantive questions back to their field of inquiry in the scholarly domain (Quadrant 2 in the chart below).

Once such disputes drift into the administrative domain (Quadrant 3), the dilemmas can be acute. At what point do “uncollegial” criticisms of research, researchers, or the institution itself justify sanctioning university professors? And if they believe that a sanction interferes with their academic freedom, can they be directed not to say so?

So far, the short unhelpful answer here is: “it depends”. Two court examinations (each over 75 pages long) mapped the murky depths of the dispute in detail – and came up with starkly different results. Three of the four judges differed on how far JCU’s Enterprise Agreement (EA) provisions on Intellectual Freedom (IF) allowed Ridd to air his concerns on Reef research and JCU’s sanctions, and how far its Code of Conduct (Code) provisions restricted him.

Within JCU, each of the parties had been “living in a parallel university”. This arose mainly from complex overlaps between the EA and the Code.

The EA notes in Clause 13 that its parties support the Code; but also that the Code “is not intended to detract from EA Clause 14, Intellectual Freedom”. For its part, Clause 14 says that “JCU is committed to act in a manner consistent with the protection and promotion of intellectual freedom … and in accordance with JCU’s Code.”

Clause 14 notes that IF has limits: all staff have the right to “express unpopular or controversial views” (but) “this comes with a responsibility to respect the rights of others and they do not have the right to harass, vilify, bully or intimidate those who disagree with their views”; and also the right to “express disagreement with University decisions and with the processes used to make those decisions” (but) “Staff should seek to raise their concerns through applicable processes…”.

However, JCU’s censure of Ridd in 2016 didn’t refer to the EA at all. Instead it drew from a longer list of items under the Code’s four Principles (1. Seek excellence as part of a learning community; 2. Act with integrity; 3. Behave with respect for others; 4. Embrace sustainability…).

The Code’s list of rights and restrictions (52 items plus a 10-page Explanatory Statement) reiterates those in the EA, such as the “right to freedom of expression … (that) is lawful and respects the rights of others”. As detailed later, the 2019 court ruling recognised how the Code could detract from the EA’s IF rights. In setting aside the dissenting judge’s concerns, the 2020 majority ruling didn’t recognise this.

Recalling the French Review warning that terms such as “lack of respect” may be applied widely, here it’s worth noting that the word “respect” appears in a dozen formulations in the Code. If strictly enforced in a Hogwarts-style “Umbridge mode”, even an informal remark in a private exchange may be deemed misconduct.

As frictions spiralled at JCU, that’s what happened to Ridd. In its 2016 censure (of his email to the journalist) JCU drew from Principle 1: “value academic freedom, and enquire, examine, criticise and challenge in the collegial and academic spirit of the search for knowledge, understanding and truth” and “have the right to freedom of expression, provided that our speech is lawful and respects the rights of others.” And from 2: “behave in a way that upholds the integrity and good reputation of the University.”

JCU found that Ridd had failed to “act in a collegial way”, “respect the rights of others” or “respect the reputations of other colleagues” by “calling into question their … integrity” (citing Principle 1); and had failed to “uphold the integrity and good reputation of the University” (citing Principle 2). In sum:

…in maintaining your right to make public comment … it must be in a collegial manner that upholds the University and individuals respect …

JCU Senior Deputy Vice-Chancellor Chris Cocklin, 29 April 2016

The second complaint arose in August 2017. In a TV interview about his essay on “The extraordinary resilience of Great Barrier Reef corals and problems of policy science”, Ridd reiterated points made in the essay:

…the science is coming not properly checked, tested or replicated and this is a great shame because we really need to be able to trust our scientific institutions … I think that most of the scientists who are pushing out this stuff, they genuinely believe that there are problems with the reef. I just don’t think that they are very objective about the science they do. I think they’re emotionally attached to their subject…

Peter Ridd, interview with Alan Jones and Peta Credlin, SkyNews 1 August 2017

This prompted a further complaint from Professor Hughes. In late August JCU formally advised Ridd that his alleged “serious misconduct” was being investigated, and directed him to keep the matter confidential. Within days the fact that he was at risk of being sacked was being reported in the media and discussed by colleagues and students.

Ridd engaged lawyers to respond, calling on JCU to drop its charges. In September and October, JCU sifted his email correspondence. In various messages, it found, he had “denigrated” colleagues and the university. For example, by suggesting to one supporter that he had “offended some sensitive but powerful and ruthless egos”; and to another, that universities took an “Orwellian” approach to free speech.

In October a 128-page document listed 25 further allegations, to which Ridd responded. In its formal letter of censure in November, JCU said it was not that Ridd had “expressed a scientific view that is different to the view of the University or its stakeholders”; but that he’d done so in ways that breached the Code. Concerned about his correspondence, it added what the courts called a “No Satire Direction”:

it is the University’s expectation that you will not make any comment or engage in any conduct that directly or indirectly trivialises, satirises or parodies the University taking disciplinary action against you.

JCU censure letter, 21 November 2017

But Ridd had had enough. That week he launched legal proceedings against JCU’s sanctions. He said he hoped that this would

draw attention to the quality assurance problems in science and the obligation of universities in general to genuinely foster debate, argument and the clash of ideas…

Peter Ridd, reported in The Australian, 21 November 2017

He then campaigned publicly, defying directives to keep the matter confidential. In May 2018, JCU dismissed Ridd for having repeatedly “breached … the confidentiality of disciplinary processes” and “denigrated the university and … colleagues”. In a public statement JCU insisted that Ridd had been free to question others’ research; however:

the university has objected to the manner in which he has done this. He has sensationalised his comments to attract attention, has criticised and denigrated published work, and has demonstrated a lack of respect for his colleagues and institutions…

JCU Deputy Vice-Chancellor Iain Gordon, reported in The Australian, 23 May 2018

The National Tertiary Education Union opposed Ridd’s dismissal. As a signatory to JCU’s EA, the NTEU shared Ridd’s view that the IF clause allowed him to criticise others’ research, and JCU’s sanctions as well. As the ABC reported, the news had chilling effects: many JCU academics stopped using their office email accounts; and worried about past messages they’d assumed were personal. Many observers found JCU’s rationale for its decision unconvincing. A Guardian journalist commented:

Would the university have behaved in the same heavy-handed way – trawling through emails for evidence, insisting a staff member it has disciplined may not discuss it – if the academic had been a mainstream climate scientist calling into question the work of a sceptic in a colourful and, at times, disparaging way?

Gay Alcorn, Peter Ridd’s sacking pushes the limit of academic freedom, 5 June 2018

To JCU critics the 2019 court ruling appeared to confirm its lack of commitment to academic debate. In a commentary in The Australian, one critic argued that JCU had used its Code as a “weapon” against academic freedom:

trawling through Ridd’s correspondence in a distinctly Orwellian manner … Actions and words parsed and censured … Rather than starting from the principle of intellectual freedom … JCU used its lengthy and loquacious code of conduct to restrain Ridd … The enforcers chose censure and sacking over debate…

Janet Albrechtsen, That’s code for ‘conduct yourself as we tell you’, 24 April 2019

The 2019 and 2020 court rulings both criticised JCU for including “incredibly trifling” and “undoubtedly trivial” instances of “disrespect” to build its case. The 2020 ruling (in JCU’s favour) put it this way:

disciplinary action in several instances of what can only be regarded as trivial breaches of the Code of Conduct did not reflect the highest standards of ethical conduct. Nor did JCU’s conduct in searching Professor Ridd’s email account in order to uncover additional breaches … The unethical approach to the matter was compounded by the direction to Professor Ridd that he was not to speak to his wife about the disciplinary matter, albeit that the direction was revoked almost one month later.

Judges Griffiths and Derrington, Full Federal Court, 22 July 2020

Unlike the Circuit Court in 2019, the full Federal Court accepted that Ridd’s IF rights didn’t mean that JCU couldn’t direct him to keep details of the disciplinary process confidential. An exception, on the other hand (in the view of the dissenting judge), was that confidentiality couldn’t apply to “the existence of the disciplinary process” itself, since this would create:

a Kafkaesque scenario of a person secretly accused and secretly found guilty of a disciplinary offence but unable to reveal, under threat of further secret charges being brought, that he or she had ever been charged and found guilty.

Judge Rangiah, Federal Court, 22 July 2020

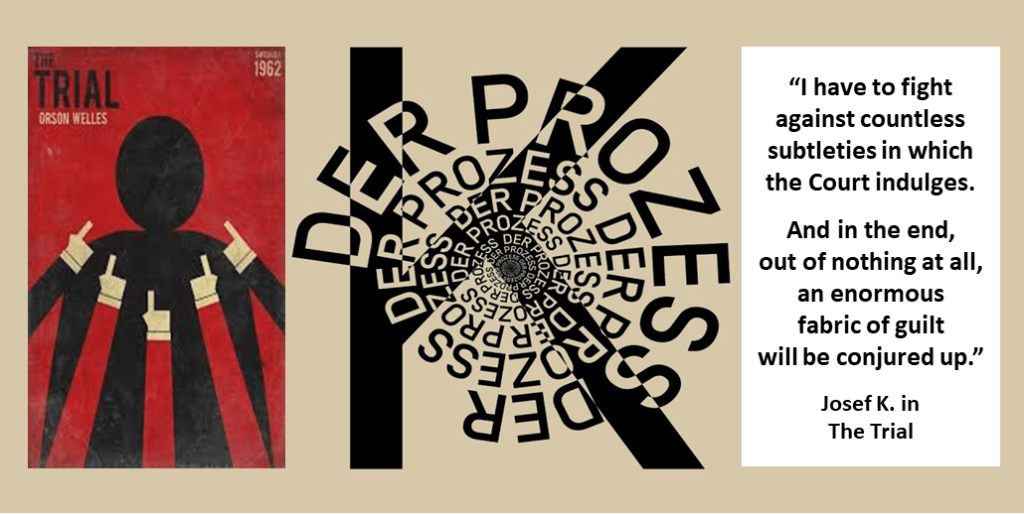

To many, the bureaucratic logic that condemns Ridd’s “pattern of misconduct” will recall Kafka’s novel The Trial, where the accused must “fight against countless subtleties”. In this case, roughly as follows:

2016: “We’ve had a complaint. If your expert view is that your colleagues’ research is unreliable or misleading, of course you are free to say so. (As Principle 1 of the Code says, we ‘value academic freedom’). But if you disrespect them (by calling their research unreliable or misleading), that is a breach of the Code. Principle 1 tells you to be ‘collegial’. And if you say that one of our institutes uses ‘spin’ to promote its research, that is a breach. Principle 2 tells you to ‘uphold the University’s reputation’.”

2017: “Another complaint. You have breached Principles 1 and 2 by denigrating others’ work. And Principle 3, which tells you to show ‘respect and courtesy’. No, you may not tell your wife about this. We found personal messages in your office email suggesting that another professor did not have ‘any clue about the weather’. And that, having offended those who are ‘powerful’, you will not be treated fairly. And that universities are ‘Orwellian’ towards free speech. And that a media report of your situation may ‘amuse’ your friend. These too are breaches. You are directed not to ‘trivialise’ or ‘satirise’ the University’s disciplinary actions against you: to do so is not in the ‘best interest’ of the University as it does not uphold our reputation (Principle 2). To disclose any of our sanctions, or your view that these restrict your academic freedom, is also a breach (Principle 2). To express frustration to your Dean (as he dictates what you can’t say in your next lecture, Professor) is also disrespectful (Principle 3). (Of course, you are free to disagree with our process and our decisions. But only through an ‘applicable process’.)”

2018: “All details of this matter, including the existence of this disciplinary process, are confidential. These and other such breaches justify your dismissal. This letter of termination is strictly confidential”.

As noted, Ridd’s legal challenge succeeded, at first. In 2019 the Federal Circuit Court ruled that all of JCU’s findings, directives and sanctions were “unlawful”. Judge Vasta concluded that the EA gave Ridd the right to express “uncollegial” views in his field, within the constraints outlined in Clause 14. Since Clause 13 said the Code wasn’t “intended to detract” from 14, the Code couldn’t add further IF constraints, such as to do so only in ways that others deemed “collegial”. He concluded also that IF included the right to “express disagreement” with JCU’s sanctions, in ways that ignored confidentiality directions. In sum:

The University has assumed that the Code of Conduct takes precedence … If (the Code) is the lens through which all behaviour must be viewed, then (EA) cl.14 is simply superfluous … Incredibly, the University has not understood the whole concept of intellectual freedom. In the search for truth, it is an unfortunate consequence that some people may feel denigrated, offended, hurt or upset…

Judge Vasta, Federal Circuit Court, 16 April 2019

The 2019 ruling accepted the logic of Ridd’s case that the EA’s IF clause was a “shield” for scholars to express views that, while “unpopular”, respected others’ (lawful) rights. Yet JCU appealed; and in 2020 the full Federal Court overturned the earlier ruling.

The 2020 decision was a narrowly technical one: Ridd’s IF shield was smaller than his Circuit Court case had claimed. It didn’t allow him to ignore lawful directions on confidential matters. Nor could he assume that the Code had no application to the way he’d professed his views, or protested against JCU’s sanctions. As the majority judges put it:

The question for decision is whether … (EA clause 14) provided Professor Ridd with the untrammelled right (provided his conduct did not harass, vilify, bully or intimidate) to express his professional opinions in whatever manner he chose, unconstrained by the behavioural standards imposed by (the Code). For the reasons that follow, it did not…

Judges Griffiths and Derrington, 22 July 2020

As the Federal Court read Clause 14, the EA gave JCU a dual commitment: to promote and protect IF and also to enforce the Code. From Principles 1-3 the majority judges cited 10 of the Code’s 52 items as relevant. They allowed that “vague and imprecise language” left room for doubt as to which of Ridd’s actions counted as a breach: some did seem to fall within his IF rights (such as the journalist email and TV interview); but not others (such as refusing directions designed to “cast a cloak of confidentiality” over the disciplinary process). Since Ridd’s case didn’t dispute that he’d breached the Code in its own terms, JCU won its appeal.

The majority judges accepted the logic of JCU’s view that the EA “informs the content of the exercise of intellectual freedom” and the Code “regulates the manner in which that freedom may be exercised”. As for Clause 13, this was:

no more than a statement of intent by JCU not to diminish its commitment to promote and protect intellectual freedom by means of the Code of Conduct. The Code of Conduct does not do so…

Judges Griffiths and Derrington, 22 July 2020

However, the assumption that the Code didn’t detract from IF relies on a curious distinction between “intellectual freedom” and “academic freedom” (AF). This didn’t arise in the Circuit Court discussion at all. Nor (it appears) in the formal sanctions that Ridd was given, which disallowed his view of his “academic freedom” rights under the EA. The distinction appears to have been discovered while JCU was preparing its appeal to the Federal Court. It draws on the French Review comment that AF has “no settled definition”. However, it ignores how often AF and IF are used interchangeably, as experts note; and as the Review itself shows.

The majority judges accepted that, since the Code refers to “academic freedom” but not “intellectual freedom”, JCU could give AF “additional content” and apply this to the academic exercise of IF. But in accepting AF as a (readily redefinable) subset of IF, the majority judgment fails to recognise that JCU applied the Code more restrictively than the EA’s own IF limits indicate.

As both courts noted, no-one accused Ridd of breaching the EA’s explicit “harass, vilify, bully or intimidate” restrictions. Nor did JCU accuse Ridd of breaching other legal constraints on IF implicit in the EA (of which both courts were aware), such as the right not to be defamed. As Judge Vasta noted, JCU’s 2016 censure didn’t specify how Ridd had failed to “respect the rights of others” – which would have breached the EA’s clause 14 as well as the Code.

However, the 2016 censure did say that he’d failed to “respect reputations”. This phrase wasn’t among the 10 “relevant” items the majority judges quoted from the main part of the Code. It arises indirectly, in the Code’s Explanatory Statement for Principle 1:

the right to freedom of expression … comes with a responsibility to respect the rights and reputations of others … staff must not engage in hate speech…

JCU Code of Conduct – Explanatory Statement (Principle 1)

Here the term “hate speech” echoes the legal constraint on “vilification” in Principle 3 of the Code (which refers mainly to anti-discrimination law). The 2016 censure conflates a legal constraint on vilification with a Principle 1 obligation to “criticise and challenge in the collegial and academic spirit” – here read as “respecting” professional reputations.

The majority judges dismissed Judge Vasta’s view that the Code “attempt(s) to rewrite” the EA’s IF clause. But the 2016 censure conflates “respect”, “rights” and “reputation” by applying Code phrases in a way that sets limits on IF beyond the legal constraints that apply to free speech generally. The censure expressly invokes Principles 1 and 2 (but not 3); then directs Ridd to profess his views “in a collegial manner that upholds the University and individuals (sic) respect”.

Later sanctions use “denigration” – a term not found in the Code at all. But as noted, the term “respect” often surfaces – like a lionfish of uncertain origin. As the French Review observed, such terms are easy to apply restrictively. In its 2017 censure, JCU refers to “respect and courtesy” from Principle 3. Without invoking anti-discrimination law (which rules out “denigration” of someone on the basis of who they are, not what they’ve done), the phrase serves a similar purpose, which is to construe dismissive (uncollegial) remarks as unacceptable.

(And if “mocking a colleague” amounts to “denigration”, one critic of the 2019 ruling argued, a court should deem this a breach of the EA itself, because “to denigrate is to vilify”. In other words, “respect” is a term that is open to “concept creep” and in turn, Orwellian application to any meaningful conception of academic freedom, in this case along the lines of the EA giveth, but the Code taketh away.)

Meanwhile, as the dissenting judge argued, the 2020 majority finding didn’t address exactly how the EA/Code overlap should have been applied to each incident in the case, to see if it amounted to misconduct, and whether each of JCU’s sanctions was justified. This is why Judge Rangiah proposed a further Circuit Court trial (which the majority didn’t agree to).

In sum, even legal boffins may be baffled, by the slippery terms and weedy syntax of JCU’s policy settings. And if the deep dives of four judges fail to fathom where they draw lines on academic freedom, how are staff to know if they’re crossing one?

In disputing the majority view, Judge Rangiah agreed that JCU was bound to apply the Code; and that in some scenarios, to do so would support the EA’s IF rights. But crucially, not in others: “There will be a conflict between JCU’s twin commitments … where a staff member exercises intellectual freedom (under the EA) and, at the same time, is alleged to have breached the (Code) standards … it is difficult to see, for example, how an academic could make a genuine allegation that a colleague has engaged in academic fraud without being uncollegial, disrespectful and discourteous and adversely affecting JCU’s good reputation…”

Echoing Judge Vasta’s view of Clause 13, Judge Rangiah clarified its implications: when conflicts arise between a “genuine exercise of intellectual freedom” and a Code requirement, the EA’s clause 14 “prevails to the extent of the inconsistency”. (In other words, the EA clause was designed to work in the same way that the French model code is designed to work.)

In such cases, JCU can’t base a sanction on Code expectations alone, and also meet its EA obligations. Unless the EA/Code overlap supports each sanction, the legitimacy of Ridd’s dismissal – even for later Code breaches that don’t entail IF – can’t be settled. This is because JCU’s final decision was:

the product of a cumulative assessment (that) … relied upon the initial (2016) formal censure and then the final (2017) censure having been issued … I do not think that it is appropriate to finally determine only some of the factual issues in the appeal, when they are all interlinked with the proper application of the Enterprise Agreement…

Judge Rangiah, 22 July 2020

Whether the case will be reviewed by the High Court, time will tell. Meanwhile, any policy in this area must recognise that in the work of universities (as scholars recognise), dissensus runs deep.

Put simply, their main mission is: ADVANCE LEARNING ALWAYS. To promote this, they urge scholars to PROFESS TRUTH ALWAYS. But, since “speaking truth to power” poses risks, they offer to PROTECT ACADEMIC FREEDOM ALWAYS. But, since unlimited free expression may harm others, they urge scholars to RESPECT RIGHTS ALWAYS.

In view of these tensions the French Model Code accepts that, often, “lawful speech” will offend. Any sharp critique that sets out to “expose error” (as a Kant or Newman would say) may challenge a majority belief, impede a majority agenda, offend a major stakeholder – or dent the reputations of other scholars. In the face of these realities, the French Review‘s stance is clear:

of fundamental importance is the necessary freedom of academic staff … to transcend their status as employees … without unnecessary restrictions on their freedom to express themselves, imposed by reason of managerial concerns about ‘reputation’ and ‘prestige’ or the effect of their conduct on government and private sector funding…

French Review, March 2019

(While the term doesn’t arise in the Review, this stance suggests that academics should be “loyal to the mission” of the university, even if doing so is not seen as “loyal to the strategy” or “loyal to the tribe”.) Where policy reflects this stance, the most practical and professional way to respond to an “offensive” claim such as Ridd’s is not to complain, but to “reject his arguments loudly, with evidence”. A side-benefit for university leaders would be less time and energy spent on adjudicating intricate disputes. As one university vice-chancellor commented recently:

Most months, someone demands I sack an academic for writing something outrageous. Almost invariably, if they had just as pungently written the precise opposite, I would have a letter of commendation. I usually suggest the complainant publish their own rebuttal…

Greg Craven, Free speech a character test for vice-chancellors, 27 July 2020

As the French Review notes, universities also have a duty to “foster the well-being of staff and students”. This makes it hard to argue in principle with any code designed to support what JCU called a “safe, respectful and professional workplace”. But (as the Chicago stance makes clear) it’s one thing to encourage civility, and another to enforce it.

On topics where dissensus runs deep, stakes are high or partisan rancour is common, there’s a dark and damaging downside to any vague but formal institutional requirement that tells scholars to RESPECT REPUTATIONS ALWAYS. Strictly applied, such a rule can create a culture of fear and favour, where academic freedom exists in name but not in norms; and where the practice of academic collegiality slides into collusion and self-censorship. In this scenario, the unwritten code will be AVOID UMBRAGE ALWAYS. Whenever complaints or disputes arise, the system response may then resemble the “administrative overreach” that the French Review warned of. In other words, as Harry Potter fans would recognise, academic freedom may be undermined by a kind of “Umbridge-Umbrage Syndrome” – too many rules, too widely and strictly applied.

In an interview after JCU’s court win in 2020, a weary and perplexed Ridd said:

One of the things which I was fired for … was that in an email I said to a student that I thought that universities were “Orwellian” because they pretended to value free speech but they don’t. And they read that email and said: “You’re not allowed to say that”…

Peter Ridd, interview with Andrew Bolt, SkyNews 22 July 2020

Experts on the uses and limits of academic freedom also find aspects of the case perplexing. A law professor who has co-authored a new book in this area observes that: “universities are not ordinary workplaces … Academic freedom exists to ensure we have the kind of environment that enables us to pursue knowledge … I don’t think you should be allowed to vilify someone … But I don’t think this general standard of having to be civil … is appropriate … Can you believe that a university in the 21st century is issuing a ‘No Satire Direction’ to an academic? I think it’s just nuts … Universities have lost sight of the really core things about the enterprise of being a university”. Another law professor sees the 2020 Federal Court ruling as wrong on technical grounds: “but the substantive problem is that an established academic like Ridd, alleging serious research errors, can be silenced and even fired for effectively speaking his mind. This is no testament to free speech in our universities, whatever the legal outcome”.

In conservative media commentary, one of the university sector’s sharpest critics put the point more bluntly:

One clear measure of academic freedom is that feathers — meaning egos — are ruffled. If your core business is collegiality, open a day spa.

Janet Albrechtsen, 15 August 2020, Australia’s universities should be penalised for crimping intellectual freedom

The Ridd case is extraordinary. In itself, it doesn’t indicate any systemic academic freedom crisis in the university sector. That said, it’s worth recalling the sector’s capacity for complacency. In late 2018 (after Ridd’s widely condemned dismissal), sector leaders argued that the French Review itself was unnecessary. Their evidence? An assertion that: “A culture of lively debate and the vigorous contest of ideas is strongly in evidence on Australian university campuses”. And an assurance that: “Between them, Australia’s (40-odd) universities have more than 100 policies, codes and agreements that support free intellectual inquiry…”

In light of the governance vagaries of the Ridd case, such a volume of policies may not reassure sceptics – or any scholar cut off or cast adrift for airing the wrong kind of view, or criticising the wrong colleague. One sceptic’s response to the “100 policies” line was to note that famously, the Enron company business ethics guidelines “ran to more than 60 pages”.

As noted, the Review found no crisis, but a problem with vaguely written rules. It observed that attempting to review these sector-wide would be “like cleaning the Augean stables“. Arguing that a workplace culture “powerfully predisposed” to free expression was critical, it also observed that: “the recitation of a generally expressed commitment to freedom of speech and academic freedom does not of itself provide strong evidence of the existence of such a culture”. Reading this, researchers of organisational learning might recall Argyris and Schon’s famous distinction between “espoused theory” (the principles said to guide conduct) and “theory in use” (the undeclared rules that guide practice).

To many, the Ridd affair highlights the issue raised by the Review. In response to JCU’s claim that “Within our very DNA is the importance of promoting academic views and collegiate debate”, higher education journalist Tim Dodd put it this way: “it is exactly the lack of commitment to academic and collegiate debate that is the problem. If the university had taken Ridd’s scientific objections to findings about damage to the Barrier Reef seriously, it’s very unlikely that this debacle — which is highly damaging to the university — would have occurred”. (In 2018 one former university vice-chancellor, Don Aitkin, predicted that “JCU’s reputation can only worsen as the trial continues”.)

For such reasons, the NTEU supports the adoption of the French Model Code, and aims to enshrine strong protections for academic freedom in EAs across the sector. As noted, the current review of universities’ progress in adopting the Model Code will report to the Education Minister later this year. As they compare policy and practice with the Model Code and the Review findings, here are four questions for university leaders to consider.

- In practice, how often is a sincere academic endeavour scuttled on some reef of collegial umbrage, when someone fails to defer to a majority view in their field, or the way its proponents promote it?

- Does your institution’s code of conduct offer broad scope to sanction those who challenge what they see as flaws or biases in the views of colleagues, due to complaints on grounds other than unlawful speech that infringes others’ rights?

- At what point may the use of professorial influence or executive authority to restrict a scholar’s robust yet sincere critique be characterised as bullying, under code definitions?

- Is your code as clear and simple as it could be? (It won’t be if it says something like: “With respect to the concept of ‘upholding respect’ the Code requires us always to respect others’ rights to respect and reputation, respectively”.)

The obligation to promote and protect “free intellectual inquiry” has been built into Australia’s higher education support legislation for years. In devising its Model Code the French Review worked hard to preserve institutional independence from direct government intervention. But for the sector’s many critics, this won’t be enough. Organisational culture matters. And institutional leadership and governance shape culture. While French didn’t suggest it, a future review might call for Ministerial power to sanction a university for failing to uphold academic freedom; pour encourager les autres, as Voltaire would say.

Notes and further reading

Since posting I’ve made minor alterations, and have added to the reading list below. As that list shows, there are many perspectives on the case. The policy issues examined here should be debated widely and openly in Australian universities.

This is an independent perspective based on information in the public domain. There are no personal or professional links to any party in the Ridd case. The view put here is informed by a longstanding interest in the public role of universities, academic freedom, and higher education policy, management and governance. In 2019, I advised two universities on their policy responses to the French Review.

Readers who find my critique of the case persuasive may infer that, if I were a professor teaching higher education policy and management at James Cook University, under its current regime my publication of this piece of independent analysis might well be seen as a form of misconduct. Not least, for suggesting that the treatment of Professor Ridd was, at times, “Kafkaesque” and “Orwellian”.

Update February 2021

Reports confirm that later in 2021 Australia’s High Court will hear Ridd’s appeal against the 2020 Federal Court decision in JCU’s favour, which had overturned the 2019 Circuit Court ruling that Ridd’s dismissal in 2018 was “unlawful”. As a policy analyst with no legal training, my own “inexpert” view is that the university will “lose the war” in a matter that should have been handled in the scholarly domain in the first place – not the university’s administrative domain, and not in the courts.

Update November 2021

The High Court ruled on Ridd’s appeal in October 2021. Details and further discussion here.

Further reading

Jon Day, 27 April 2016, Great Barrier Reef bleaching stats are bad enough without media misreporting

Graham Lloyd, 31 January 2018, Reef row scientist Peter Ridd snubs uni gag order

Katharine Gelber, 9 May 2018, As Melbourne University staff strike over academic freedom, it’s time to take the issue seriously

Graham Lloyd, 19 May 2018, Marine science rebel Peter Ridd sacked by James Cook University

Don Aitkin, 23 May 2018, Don’t you dare upset the money-making engine

Tim Dodd, 23 May 2018, Sacked academic’s $160,000 legal bid

Gay Alcorn, 5 June 2018, Peter Ridd’s sacking pushes the limit of academic freedom

Graham Readfearn, 7 June 2018, Academic Peter Ridd not sacked for his climate views, says university

Peter McCutcheon, 14 June 2018, James Cook University staff avoid using emails after climate change sceptic sacked

Michael McNally, July 2018, Ridd sacking a blow to academic freedom

Glyn Davis, Adrienne Stone and John Roskam, 23 June 2018, Academic freedom and free speech in universities

Adrienne Stone, 15 October 2018, Four fundamental principles for upholding freedom of speech on campus

Universities Australia, 14 November 2018, Freedom of expression alive and well on Australian uni campuses

Gareth Hutchen, 14 November 2018, Universities warn against meddling as inquiry into free speech announced

John Roskam, 15 November 2018, The heavy hand of free speech

Katharine Gelber, 15 November 2018, There’s no need for the ‘Chicago Principles’ in Australian universities to protect freedom of speech

Glyn Davis, 4 December 2018, Special pleading: free speech and Australian universities

Fergus Hunter, 16 April 2019, Sacking of James Cook University professor was ‘unlawful’, court rules

Elias Visontay and Tim Dodd, 18 April 2019, Uni case ruling backs freedom of speech

Tim Dodd, 19 April 2019, The Ridd affair is a debacle for JCU and its council should look into it

Jo Khan, 23 April 2019, Are climate sceptic Peter Ridd’s controversial reef views validated by his unfair dismissal win?

Stuart Andrews, 24 April 2019, Court ruling raises some questions

Janet Albrechtsen, 24 April 2019, That’s code for ‘conduct yourself as we tell you’

John Ross, 12 May 2019, Scientists ‘must be free to question the unquestionable’

Paul Kelly, 19 June 2019, Freedom should be a no-brainer

Jacqui Maley, Jordan Baker and Tim Elliott, 20 June 2019, Is there a free speech crisis in Australia’s universities?

Katharine Gelber, 24 June 2019, Dan Tehan wants a ‘model code’ on free speech at universities – what is it and do we need it?

Paul Kniest, 11 March 2020, Where are we at with academic freedom?

Ben Smee, 22 July 2020, James Cook University wins appeal in Peter Ridd unfair dismissal case

Greg Craven, 27 July 2020, Free speech a character test for vice-chancellors

Charlie Peel, 29 July 2020, Sacked JCU scientist Peter Ridd seeks High Court appeal

Henry Ergas, 31 July 2020, Ridd decision abandons the point of universities

Michael Koziol, 2 August 2020, Academic freedom on trial as sacked professor asks High Court to decide

Janet Albrechtsen, 15 August 2020, Australia’s universities should be penalised for crimping intellectual freedom

Peter Ridd, 16 September 2020, Scientific cancel culture exposed

John Ross, 15 October 2020, Are corporate overreach and political correctness really undermining academic freedom?

James Allan, 26 October 2020, Academic peers gag their own

Lisa Visentin, 28 October 2020, Academic freedom definition would have protected sacked JCU professor

Robert Bolton, 11 February 2021, Climate cases shapes as test of academic freedom

Toby Crockford, 11 February 2021, Sacked Queensland professor scores first win in High Court Appeal

Olivia Caisley, 11 February 2021, Sacked James Cook University physicist to have case heard in High Court

Jordan Hayne, 12 February 2021, Marine scientist Peter Ridd gets chance to fight James Cook University dismissal in High Court

Tim Dodd, 2 May 2021, Australian Association of University Professors backs Peter Ridd

Graham Lloyd, 8 May 2021, James Cook University in hot water over claims of fish fraud

Nick Bonyhady, 31 May 2021, How a fight about the Great Barrier Reef has become a free speech test

George Williams, 21 June 2021, As Peter Ridd case shows, pursuit of truth not always a civil affair

Great piece Geoff –

Thorough dissection if the twists and turns in this case.

One thing that it prompts me to think about is not just whether universities have created ambiguous and contradictory academic freedom policies – but whether universities have created institutional policy ecosystems that are so messy convoluted detailed and contradictory that any issue could find itself in similar terrain. Course design, assessment, finance, Human Resources, enrolment etc. Policies have become less ‘mode code’ like statements of principle to guide action but prescriptive statements of behavioural action that have less coherence as the system has got more complex.

Maybe with revenue reductions across the board there maybe preconditions to streamline this part of sector operations considerably.

Thanks Matt – I’m sure you’re right about “policy ecosystems” in universities.

My own early experience as a course co-ordinator for postgrads was that areas such as research ethics co-ordination could be extremely complex and time-consuming. And way out of proportion to the risks of most project proposals. I recall emailing colleagues caught up in the process about feeling like “Franz Kafka living through Groundhog Day, while reading Catch 22 and trying to decipher the DaVinci Code”. In the end, devising a “foolproof one-page template”, with standard phrases for students and staff to use, helped.

I agree about the current preconditions as a catalyst for streamlining. As in other complex enterprises, this kind of change is really hard to do – arguably more so in universities. A few years ago I did a fairly detailed internal review of the “business improvement program” (admin restructure) at my university (Melbourne). The design made sense, there was lots of consultation, the changes were planned and implemented in a carefully co-ordinated way, and overhead savings were made (at a cost of job losses). But inevitably, not like clockwork – a very long, hard, and disruptive haul for all concerned.

The sad truth is that the current government is only interested in free speech as part of the pathetic “culture wars” so beloved of a particular part of the media. There’s no real commitment to the concept and it wouldn’t survive for long if academics started taking awkward stances on topics close to their hearts. For instance, there’s strong support for Ridd (with his anti-climate change agenda) but significantly less for Tim Anderson at USyd (for use of a swastika).

So Heaven forbid that the exercise of any “Ministerial power to sanction a university for failing to uphold academic freedom” is left to the judgement of a member of Her Majesty’s Government, of either political stripe. And especially not one of the current conservative/reactionary axe grinders in power, although I doubt most Labor politicians would be much use either.

Thanks for reading Peter. Accepting your point that there is a longstanding “culture wars” aspect to the public debate about academic freedom, I think there is also evidence of a “cancel culture” problem that policymakers (and university leaders and councils) should not ignore. Criticism of universities on this front does not come only from one side of the political spectrum.

It is vital to realise that Ridd was NOT sacked for arguing about or doubting the research, he was sacked for his behaviour towards colleagues whilst making his arguments (and after). He may claim that his sacking was a denial of his intellectual freedom – that doesn’t make it so.

In the end, the case will likely turn on some arcane arguments about wording in the enterprise agreement, and probably won’t be about intellectual freedom. That would be a good outcome.

Thanks for commenting, Peter R.

I’m aware that some do read the case that way.

For example the employer association (Australian Higher Education Industrial Association) said of the first (Circuit Court) ruling that Ridd’s commentary should not have been protected by the EA as it “did not amount to the exercise of intellectual freedom within the meaning of that clause, or for any statements he made, whether or not they were an exercise of intellectual freedom, that involved vilification of others. The exercise of intellectual freedom should not give anyone an unfettered right to denigrate or offend. This is a fundamental expectation of civil discourse.”

That view was published in The Australian, back in April 2019. As I see it, the problem with the university as employer interpreting any professor’s suggestion that another professor’s expert’s view is nonsense as a code breach in the form of “disrespect” (aka “denigration” aka “vilification”) is that if applied consistently, scholars would never feel free to dispute each other’s views publicly, at all. At that point, universities may as well not bother pretending to promote academic freedom and open exchange.

That said, I’d be interested in hearing what other readers think. And of course, what the High Court determines over the coming month.