In Australian universities, scholars and students disagree on many topics. Often a little, sometimes a lot. Usually for plausible reasons that each side deems valid enough to persuade an impartial spectator that we are right! and they are wrong!

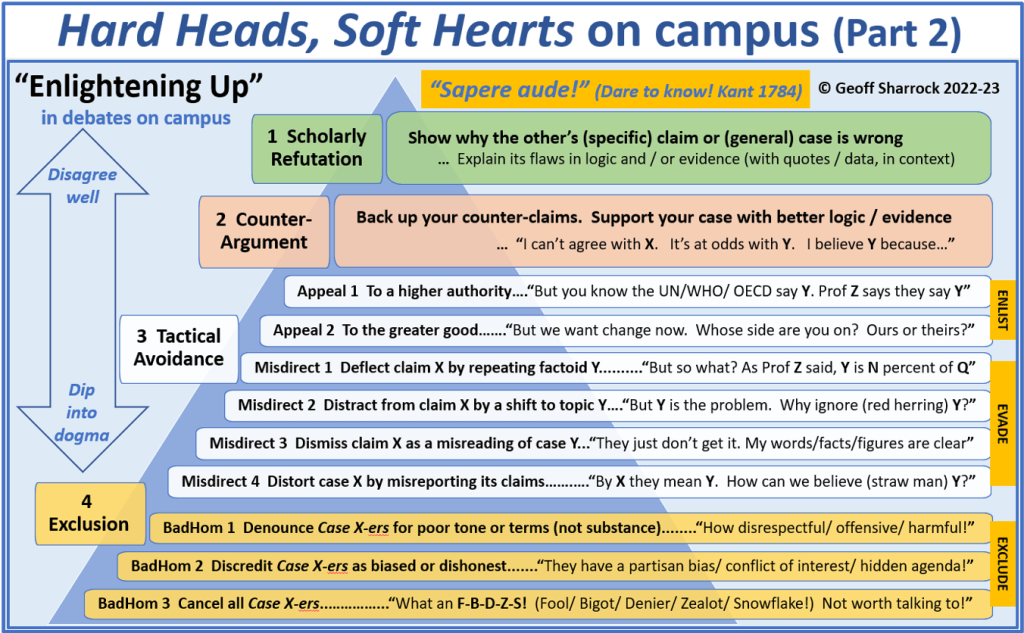

On hotly contested topics, it’s harder to disagree well. To defend their view, some shift gear to slings and arrows, barbs and slurs: we are good! they are bad! This BadHom123 mode shifts to meta-argument allegations (that opponents are morally wrong in their beliefs, or not being honest due to an agenda). These tend to exclude alternate viewpoints, shut down the space for dialogue, and entrench positions (see Chart 6).

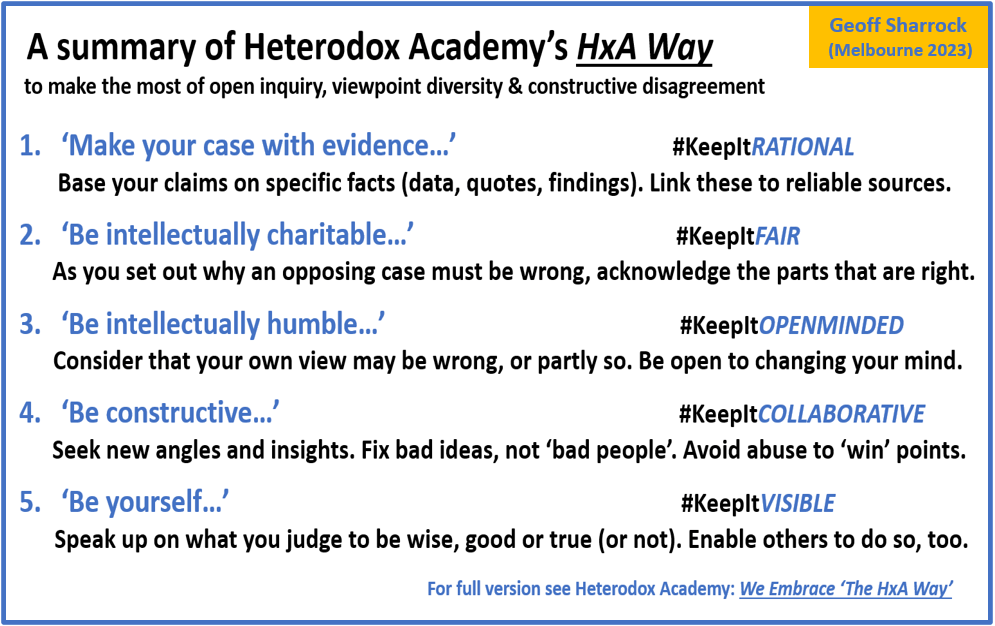

To support more constructive disagreement, the US-based Heterodox Academy offers guidance on how to do this in ways that reflect academic norms and values. In 550 words (in line with its motto: great minds don’t always think alike), “The HxA Way” sets out 5 general rules of engagement:

- Make your case with evidence.

- Be intellectually charitable.

- Be intellectually humble.

- Be constructive.

- Be yourself.

With this guidance in mind, groups can aim to engage in good-faith dialogue to absorb fresh facts, test assumptions and consider new possibilities. With all perspectives up for discussion, participants can expect to refine or rethink their own views on the matter, as they learn why others see it differently.

My summary at Chart 1 translates this guidance into shorthand, as a presentation slide.

As the hashtags here indicate, the aim is to keep scholarly debates rational and fair and open-minded and collaborative; and the range of substantive viewpoints visible.

The HxA statement itself uses none of these terms (see Notes); but none of the ideas is new. As a set of rules for a debate on (say) what constitutes the good society, Chart 1 would not surprise a philosopher such as Plato or Aristotle. So, in university settings, where scholars are expected to seek, share and strengthen truth and knowledge for the public benefits these things bring, Chart 1 should have wide common-sense appeal.

But as Voltaire put it in 1764: Sometimes, common sense is all too rare. One reason many groups find it hard to apply Chart 1 rules consistently is that most of the time, most views on most issues – however complex or contentious – are expressed in shorthand. And often in forms of language that mean quite different things to different people.

Take, for example, the term “woke” – frequently invoked in today’s culture-war contexts. To some it’s a noble virtue, to others a foolish vice. For proponents in the US (where the term originated) it refers to a socially aware, morally enlightened concern to redress systemic forms of societal injustice (such as racism). But for critics, it refers to misguided demands to rewrite rules and norms that create new forms of injustice. Jonathan Kay dissects the variable usage of the term and in the end defines it as illiberal progressivism. (The political debate on Australia’s Voice referendum echoes the negative usage of the term, as some on the No side frame the Yes case as a “woke agenda”. Among Australians who know the term, a recent report says, 45 per cent identify with being “woke”, while 55 per cent do not.)

Similar problems arise with the terms cancel culture and even viewpoint diversity. Each has currency on campuses. The former, as a critique of public allegations, usually on social media, that damage careers without due process. The latter, as a remedy for cultures that impose conformities that constrain academic work, and the public benefits it can offer. But both terms also attract counter-critiques: as concepts that (mainly conservative) commentators deploy to discredit (valid) social justice projects, or to promote (inequitable) social norms or prejudices.

The translation problem looms large on social media, where the subtext of everyday terms gets re-coded by shifts in context or audience. An innocuous use of a newish phrase may have unintended consequences. For example, in Canada a Dean of Graduate Studies was stood down from his role for posting a tone-deaf Tweet (which, once aware of its new currency, he deleted with an apology) with the hashtag #AllLivesMatters (sic). He thought he was engaging in an intellectual discussion. But many readers thought he was taking the wrong side in a political messaging contest about #BlackLivesMatter.

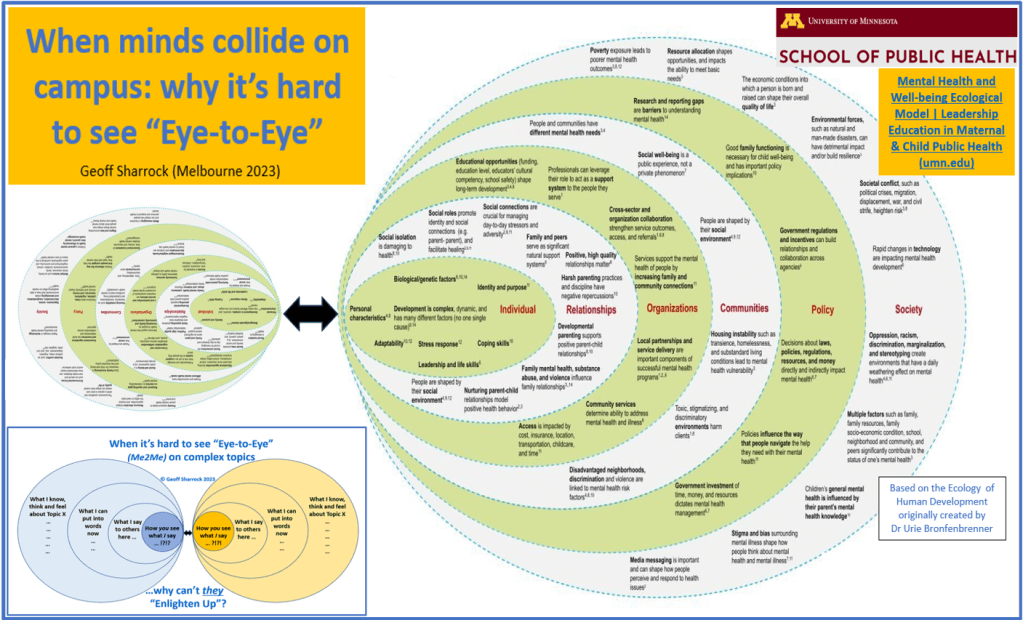

The net effect, as Chart 2 indicates, is that seeing eye-to-eye will never be the same as looking in a mirror and seeing me-to-me. To complicate things more, often the exchange is not just one-to-one but multi-lateral, with several perspectives at play.

Linguistic and ideological differences aside, my main point here (for higher learning purposes), is that all general perspectives differ to some degree. However alike in background, occupation or politics, no two people see the world in exactly the same way.

As Chart 3 illustrates, we inhabit endlessly complex social systems that constantly evolve around us. Our encounters with these entail endless variations in norms, values, priorities, biases and blind spots. These differentiate individuals’ sense of social reality, and of how social systems work (or don’t).

So, inviting others to confirm your view of what’s wise, good or true on a complex topic may entail a host of translational problems. On both sides there will be (largely invisible) layers of context, that shape our sense of the world and what’s right or wrong with it. Debates on a complex matter, such as health care or education system reform, can easily become mired in miscommunication and cognitive dissonance.

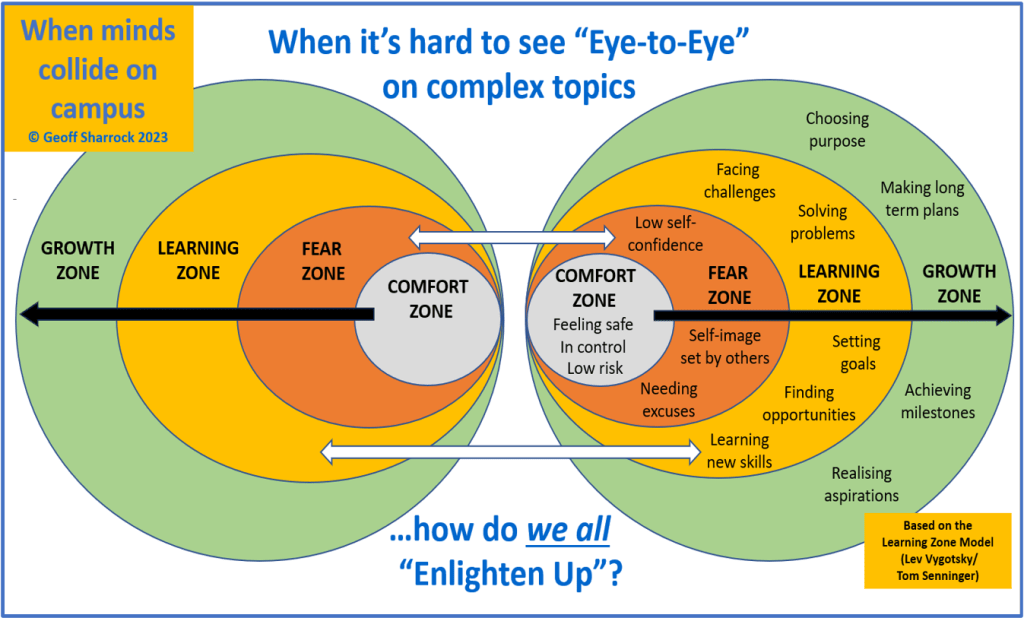

All this means that in higher learning contexts, disagreement is hard to do well in part because, on complex topics, the uncertainty this creates may feel like risk to our sense of self. To have a whole slice of your worldview challenged, and/or your integrity or intelligence implicitly called into question, can be very unsettling. This is why Oxford scholar Teresa Bejan argues that at some level, the mere act of disagreement is offensive. But as outlined, disagreement in class and on campus is how much of the work of higher learning works. For many students, a course of study in these contexts may offer a psychosocial moratorium as they form a more complex and coherent sense of self and purpose, along with new skills and knowledge.

On this view, scholars who teach controversial topics must urge or invite their students to reframe the reflex response in Chart 2 (Why can’t they Enlighten Up?) to ask instead: How do we all (here, now) Enlighten Up? (Chart 4). In these encounters, students can expect to do some rethinking and self-examination, to build clearer perspectives and better capacities to engage with those of others, during and after study.

To foster higher learning along these lines, universities can’t routinely operate as political battlegrounds. The “fear zone” will loom too large in classes to explore any controversial issue openly. As Newman put it in 1852, the basic idea of a university is to offer scholars a safe place for the collision of mind with mind. So, an intellectual gymnasium, where many modes of learning are on offer; where the norm is that these will be moderately challenging; and where at times the learning task may demand painful effort “beyond the comfort zone”.

Such an approach can be seen in recent work by some US universities, outlined in a Campus Call for Free Expression:

Colleges and universities are among the few places in the United States today where people from remarkably different backgrounds, cultures, and ideologies come together to wrestle with the complexity of what it means to be a democratic community. Underlying the Campus Call is the belief that higher education plays a critical role in preparing students to thrive and lead as empowered citizens and leaders of the future. This preparation is not easy, but it is essential. It requires an openness to all ideas and the skills to respectfully listen to, learn from, and work with people with diverse perspectives. Leaders participating in the Campus Call … aim to develop students who:

- Pursue knowledge beyond their comfort zone, challenging existing beliefs and assumptions;

- Reach informed decisions based on evidence and reasoned analysis;

- Develop a deeper understanding of self and one’s own values while potentially gaining respect, empathy, and appreciation for those with differing values and views;

- Feel a sense of civic responsibility, advocate for positive change, and contribute meaningfully to their community; and

- Express ideas freely but recognize that doing so doesn’t guarantee approval or immunity from consequences.

Along similar lines in the UK, University College London this year offers public seminars on how to disagree well. UCL President Michael Spence makes the case for this initiative this way:

For democracies … citizens learning to disagree well is not optional, but rather a core survival skill … It means facing up to disagreement and learning from the process … while disagreeing well cannot mean abandoning emotional engagement, it must begin with a particular mindset. This is a mindset of epistemic humility, of an openness to the possibility that I might be wrong, even about my passionate convictions … it is hard to imagine how genuine engagement can happen across difference unless I approach it with at least some willingness to concede that my understanding might be incomplete, or even wrong...

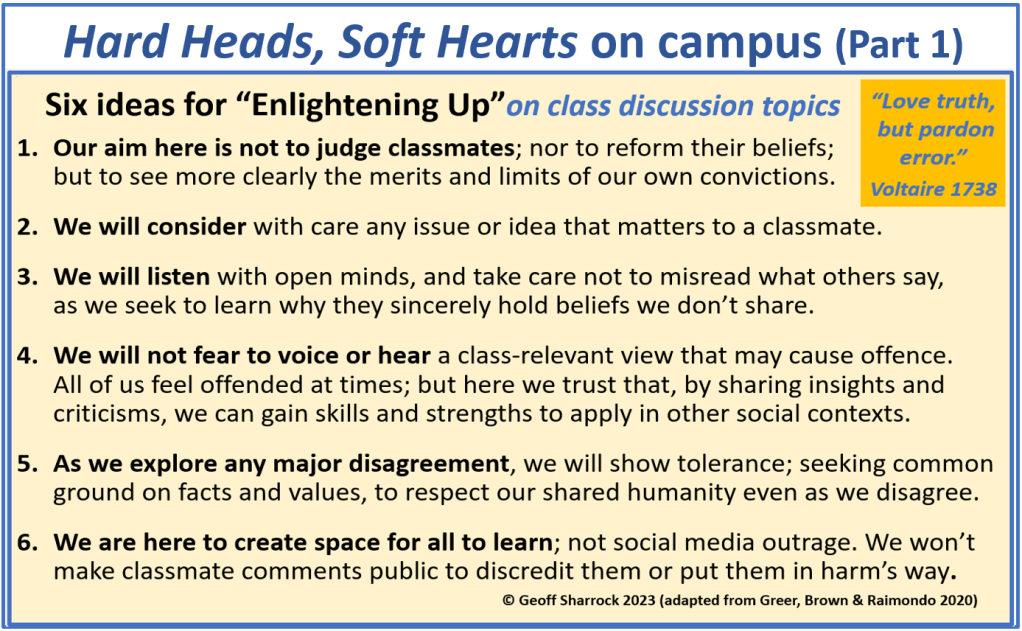

Which leads me back to last year’s Heterodox Academy project on viewpoint diversity (what I call viewpoint visibility). Its premises were that different doctrines often share truths (as none can capture the complete truth); that in a connected world, learning charity and tolerance are vital to the future of humanity; and that with any kind of political problem, furious zealots on either side can derail the kind of deliberation modern democracies need to face their problems, and to serve the causes of truth and justice and security and societal progress that most people want, all the time and everywhere.

On this view, the quality of campus debate and student learning can benefit from a “hard heads / soft hearts” approach, as outlined in earlier posts. The two main charts are reproduced below.

Notes

Heterodox Academy’s “The HxA Way”

In order to best promote open inquiry, viewpoint diversity, and constructive disagreement, we embrace a set of norms and values that we call “The HxA Way.” We encourage our members to embody these in all of their professional interactions, and we insist on these norms and values for those publishing on our platforms or participating in our events. These values can help anyone foster more robust and constructive engagement across lines of difference…

1. Make your case with evidence.

Link to that evidence whenever possible (for online publications, on social media), or describe it when you can’t (such as in talks or conversations). Any specific statistics, quotes, or novel facts should have ready citations from credible sources.

2. Be intellectually charitable.

Viewpoint diversity is not incompatible with moral or intellectual rigor — in fact it actually enhances moral and intellectual agility. However, one should always try to engage with the strongest form of a position one disagrees with (that is, “steel-man” opponents rather than “straw-manning” them). One should be able to describe their interlocutor’s position in a manner they would, themselves, agree with (see: “Ideological Turing Test”). Try to acknowledge, when possible, the ways in which the actor or idea you are criticizing may be right — be it in part or in full. Look for reasons why the beliefs others hold may be compelling, under the assumption that others are roughly as reasonable, informed, and intelligent as oneself.

3. Be intellectually humble.

Take seriously the prospect that you may be wrong. Be genuinely open to changing your mind about an issue if this is what is expected of interlocutors (although the purpose of exchanges across difference need not always be to “convert” someone, as explained here). Acknowledge the limitations to one’s own arguments and data as relevant.

4. Be constructive.

The objective of most intellectual exchanges should not be to “win,” but rather to have all parties come away from an encounter with a deeper understanding of our social, aesthetic, and natural worlds. Try to imagine ways of integrating strong parts of an interlocutor’s positions into one’s own. Don’t just criticize, consider viable positive alternatives. Try to work out new possibilities, or practical steps that could be taken to address the problems under consideration. The corollary to this guidance is to avoid sarcasm, contempt, hostility, and snark. Generally target ideas rather than people. Do not attribute negative motives to people you disagree with as an attempt at dismissing or discrediting their views. Avoid hyperbole when describing perceived problems or (especially) one’s adversaries — for instance, do not analogize people to Stalin, Hitler/ the Nazis, Mao, the antagonists of 1984, etc.

5. Be yourself.

At Heterodox Academy, we believe that successfully changing unfortunate dynamics in any complex system or institution will require people to stand up — to leverage, and indeed stake, their social capital on holding the line, pushing back against adverse trends and leading by example. This not only has an immediate and local impact, it also helps spread awareness, provides models for others to follow and creates permission for others to stand up as well. This is why Heterodox Academy does not allow for anonymous membership; membership is a meaningful commitment precisely because it is public.