As the Albanese government considers the Segal report on antisemitism (with more reports to come on other forms of racism) Australian university administrations face a new “French Review” moment. As with the 2019 Independent Review of Free Expression in Australian higher education (by former High Court Chief Justice Robert French), they’ve been working to articulate clearer, more visible lines for students and staff on “free speech” rights, “hate speech” restrictions and “respectful disagreement” on campus.

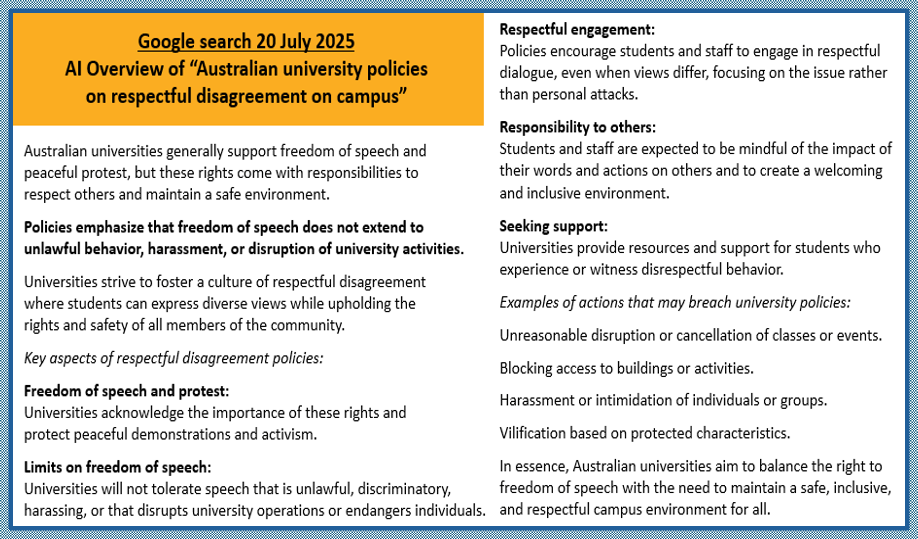

What rules should apply here? To map the key threads of current policy, last weekend I searched online for “Australian university policies on respectful disagreement on campus”. Google’s AI Overview gave a useful summary (Chart 1).

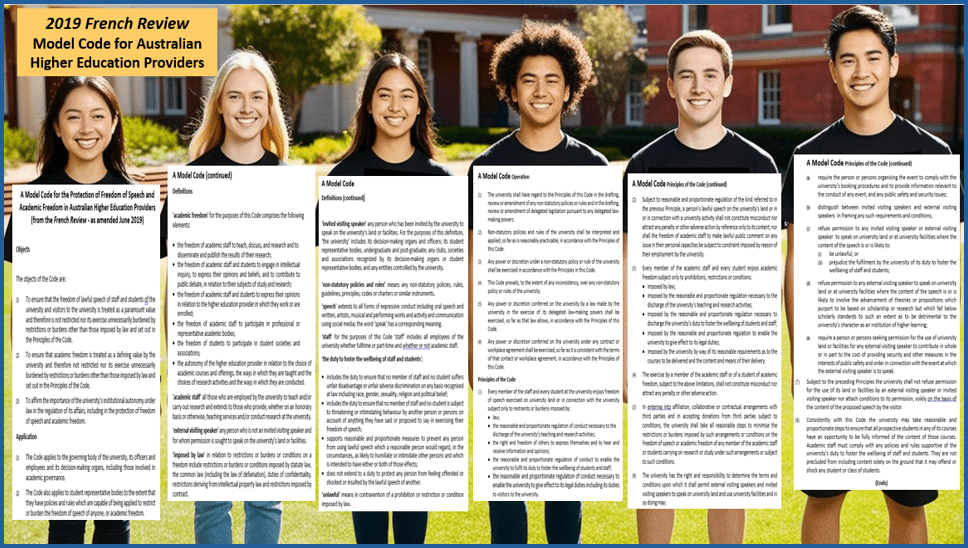

For institutions this is a complex balancing act – not least when, on many topics, wider public discourse is highly polarised. Having advised two universities in 2019 as they wrote the French Review Model Code principles into their wider policy suites, I can confirm that no full set of campus rules will ever fit neatly onto a student T-shirt (Chart 2).

In line with Australian laws and statutory rules for universities, the Code had to include definitions to “decode” its own common-usage terms. Designed as a generic set of “umbrella principles” to guide universities’ own policy formulations, it still ran to 6 – 7 pages and about 1800 words. For example, it ruled out speech that aims to “intimidate” but not speech that merely “offends”. In the wider report (300 pages) French warned that in higher learning institutions, terms such as “respect”, “harm” and “hate speech”, if defined too broadly, could be applied too restrictively for their purposes.

Reflecting on these issues in their 2021 book Open Minds, law scholars Carolyn Evans and Adrienne Stone judged it “unrealistic” to expect administrations to moderate directly the “myriad small interactions that occur daily in universities”. Or to expect students to “make detailed reference to university policy” to guide their own interactions. Echoing a point the Review made, that clearer campus rules alone wouldn’t suffice to protect lawful free expression, they argued that universities need “a culture of openness, based on a broad understanding of free speech and academic freedom”.

In the wake of recent campus protests and incidents of racism, universities have again been refining policy guidance and promoting programs that focus on what many call “respectful disagreement” on campus as a key element of higher learning.

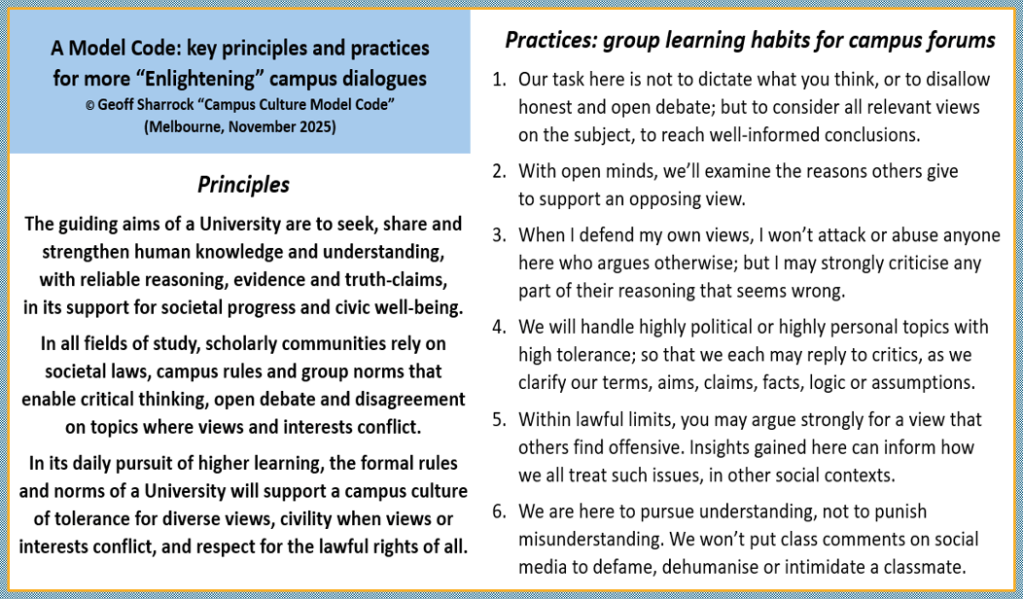

With all this in mind, Chart 3 present the latest iteration of my “Campus Culture Model Code”. The aim here is to be short, sharp and simple enough for student groups to follow as a principled-yet-practical set of learning habits. But also detailed enough to help guide complex and controversial debates on a wide range of issues, where topic awareness, term definitions, context assumptions and personal relevance may differ widely.

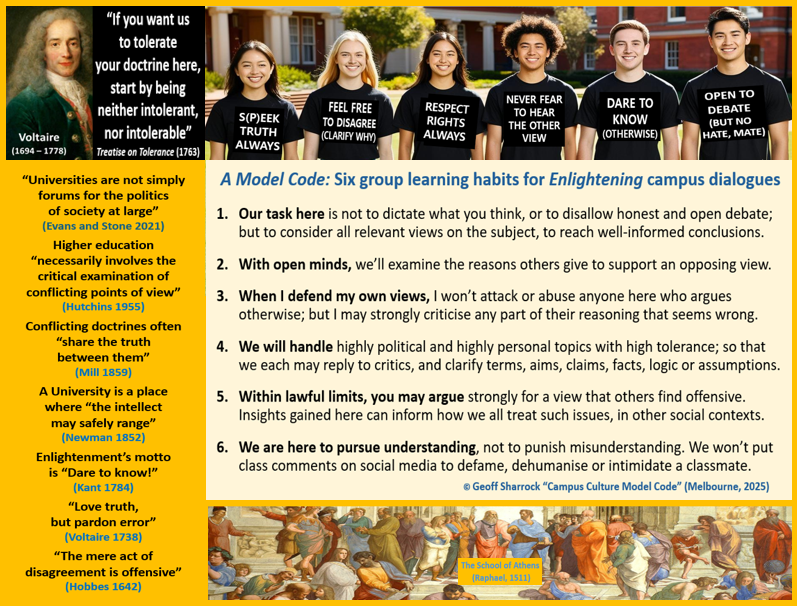

Chart 4 presents the same set of practices; this time loosely translated into student T-shirt slogans, and linked to some relevant quotes from scholars, past and present.

An earlier post gives more background to Chart 4. There I examine in detail the uses and limits of free expression in universities, and the necessity of tolerance (and the value of civility) to the work of scholarly communities.