Like a scene from Shakespeare’s Tempest, study in Australia has been swept off campus. To keep study programs afloat, staff and students alike have leapt or scrambled online. As shutdowns relax and our “tyranny of social distancing” lifts, campus life will re-animate.

The shipwreck in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Act 1. (Engraving by Benjamin Smith after a painting by George Romney, 1797). Source: Wikipedia (US Library of Congress).

But most universities now face large budget shortfalls. For many this will mean staffing cuts and projects set aside. For the rest of 2020 the sector must “suffer a sea-change” with little hope of return to business-as-usual in 2021.

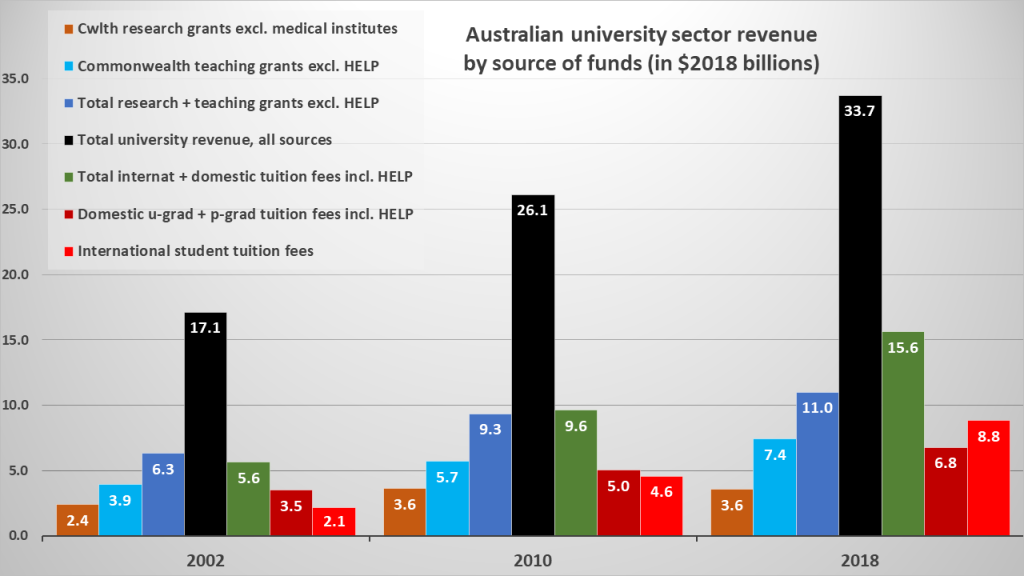

The growth curve was great while it lasted. For over a decade, and more than most in the OECD, the Australian tertiary sector has lifted real revenue from all sources, domestic and international.

In domestic data both public and private income levels rose (but trends per source are hard to show simply – see Notes). Over 2002-2018 total university sector revenue doubled to nearly AU$34 billion. Direct government grants for teaching and research rose to $11-12bn. Domestic fee income – mainly HELP loan financed – rose to nearly $7bn. International fees grew over fourfold to nearly $9bn, contributing 1 in 4 dollars of sector revenue in 2018.

But suddenly, as Shakespeare’s Prospero puts it, “our revels now are ended”. Having surfed a long boom in local and international enrolments, the sector now weathers a collapse in offshore access and with it, rivers of gold “melted into air”.

The more addicted to offshore fee growth a university’s strategy was, the more painful its sudden withdrawal is likely to be. Those with high exposure will see programs of study, research jobs and planned new facilities on hold, or at risk. An estimate of 10,000 higher education construction jobs lost next financial year highlights the scale of work underway across campuses.

No big federal funding rescue is visible on the horizon. But public cash-flow support and modest relief measures are in place. Already-budgeted Commonwealth grants and student loans are guaranteed for 2020 if domestic student numbers also fall. This cash-flow creates an $18 billion budget anchor, but adds little to offset alarming projections of international losses.

For newly unemployed locals, the short online certificates announced in April by Education Minister Dan Tehan are worthwhile. They can complete a micro-credential in 2020 with credit toward a full diploma or degree, then elect to complete the course in 2021-2022 at normal pricing. The move was met with early scepticism by some commentators. But by early May, over 20 universities had responded with over 170 course offerings.

The Minister sees potential long term benefits:

These micro-credentials address [the] immediate need to keep our workforce engaged and adding long-term career value. They present the opportunity, on the back of the pandemic, for universities to lead globally with a pivot towards a new shape of higher education for a transformed economy.

Dan Tehan

But (again) the short term, bottom-line benefits to university budgets are modest. Grant subsidies per field of study apply, but with smaller HELP loan (fee) revenue. This should help institutions expand full-price domestic cohorts in 2021-2022, and lower their risk of needing to repay unused 2020 HELP loans. As well, state-level support such as the Victorian Government package announced in May will boost local university infrastructure and industry engagement.

What else might be considered? Some suggest a return to the “demand-driven” Commonwealth funding that lifted university enrolments since 2010 (but indirectly flattened revenue in public vocational institutions). Over 2018-2019, the teaching grant component was frozen at 2017 levels, and remains capped.

Others suggest uncapping domestic student fees (at most about $11k a year today) to let these rise closer to international levels (up to say $35k), backed by HELP loans.

Both solutions are flawed. The first reflects yesterday’s logic. When announced in late 2017, the funding freeze was dubbed a funding cut and de facto enrolment cap, at odds with projections of rising demand (now set to rise more in a weaker 2021 economy).

But, to uncap publicly-financed places in a 2020-2021 context would invite a Hunger Games response from market leaders, now armed with new online capacity. In the past, most have enlarged their share of more lucrative international enrolments, to cross-subsidise research and finance new campus facilities. As noted last month in the UK university sector, a big pivot by prestigious institutions to “hoover up” domestic students would risk enrolment and budget crises at other institutions.

The second option adds other risks, ignoring past experience. The prospect of financing uncapped domestic fees with HELP loans was canvassed in 2014. As seen since, in the private vocational sector’s VET-FEE-HELP loan debacle, this is a recipe for moral hazard. Business A and client B take big risks, for which future taxpayer C must pay if things go badly.

Even with high level caps on course fees, UK experience shows how easily this induces high levels of graduate debt, often for decades. And in the end, massive write-offs.

Advocates of either move should “revise and resubmit”. Today’s context demands tightly targeted responses, with eyes wide open to longer term risks – and prospective reforms. For example, Australian research programs and researchers will need more direct funding to continue, and in future should be less reliant on student fee cross-subsidy. And in regional communities already hurting from drought or bushfire, modest injections of funding to support local universities could maintain critical program and workforce capacity to aid regional recovery, and sustain wider strategies for further regional development.

Meanwhile, many resident international students face living cost crises due to loss of part-time jobs. On compassionate grounds they deserve support; universities, state governments and charities have stepped up. If most can remain enrolled they may still continue their courses post-crisis; and this would mean fewer staff and program losses in 2021. And at the post-graduate level, many international students contribute directly to research programs.

If international border controls stay tight for years, incoming students can commence study after brief stays in quarantine (unlike short-stay tourism, this seems workable). The government has flagged such a move already. The Group of Eight universities has proposed a “secure corridor” framework for the national cabinet to consider. As a super-safe “diamond” study destination, Australia may yet fare well in the next few years – as may New Zealand.

More broadly, the sector’s future shape remains in question. In prospect now are wider future market shifts, also perilous to navigate. For example, when campuses re-open fully, will students all want to return? Or will the newly visible costs of attendance make “cloud campus” study more popular?

In turn, how far should academic teaching revert to face-to-face modes, in lecture theatres and seminar rooms? Will on-screen “guide on the side” roles finally fully displace the traditional “sage on the stage” (with its long tradition of back-row students dozing, talking or texting)?

Some crisis-as-catalyst commentators welcome the “death of the dull lecture”. Outcomes will be case by case. In fields of study amenable to digital delivery, much will turn on the student cohort profile, how well the abrupt shift online has gone, and how capably the academic and professional workforce can apply new tools and pedagogy.

Scenarios like these are not new. In 2012, some saw massive open online courses (MOOCs) taking a “disruptive technology” path. An innovation opens up “brave new worlds” (or so the fanfare promises). New models are tried and tested, to meet or get mugged by reality. Over time, markets, industries and policy settings adapt and a more productive and effective business-as-usual ensues.

To an established university, offering MOOCs in 2012 was seen as great for the mission and grand for the brand – as a supplement to core degree programs. But, grim for the business model if MOOC-based credentials suddenly went truly/madly/deeply viral. Ever since, many in the sector have assumed (or hoped) that online study can’t match the real thing. And many institutions have kept adding attractive new facilities to meet enrolment growth, and enrich the on-campus experience.

So far, the 2020 assumption has been that existing student fee levels are justified even while campuses are closed. International students don’t all accept this. Should lower-fee local students? Some already question this, unimpressed by the makeshift study arrangements experienced already.

Today’s crisis has become a real-life “action research” experiment. How much more flexible and cost-effective could tertiary study be if institutions were simply compelled to shift programs online, and scholars to “teach like our jobs depend on it”?

The good news is that for years, universities have been adding new online capacity as well as new campus facilities. Most have developed micro-credentials as tasters and add-ons, to foster new markets, attract new entrants and re-engage alumni.

The crisis offers scope for institution-level “game-change” as course design and delivery are re-engineered under “burning platform” conditions. Uncapping future “cloud study” capacity will allow for scaled-up enrolments, with less pressure to extend campus facilities.

As well, some universities still support large and Byzantine administrations. They’ll need to find ways to be “smartphone organisations” with stable and coherent core systems that are clear, simple, transparent and reliable, and which enable diverse and dynamic academic “apps” projects to be added, updated, scaled up or shut down in response to new mission and market demands.

For policy makers also, the crisis offers rare opportunity. With business-as-usual in flux, state and federal leaders have been co-operating closely in a National Cabinet forum. Navigating the pandemic has meant sharing system-level perspectives, with more pressure to act than seen under earlier Council of Australian Government skills training reforms. As in other areas of public policy (energy, tax), riding “on a bat’s back” above our politics-a-usual “reform COAGulation” may help minds meet more often.

With the National Cabinet now replacing COAG for the long haul, the coming “months in a leaky boat” to co-ordinate recovery may curb the expected snap-back to tribal/territorial incrementalism. If they can settle on a national reform strategy, Australian leaders may (finally) find ways to renew the tattered fabric of tertiary education policy.

An expert task force should draw together recent reviews, to show how best to connect new work realities with credential structures, course provider types, funding and co-funding models, and (not least) system governance across state-federal lines. Clear, coherent and responsive system governance was already high on the federal government’s to-do list for skills training. (This featured as a reform priority in Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s National Press Club address on 26 May.)

To sharpen its focus on the systemic problems of the wider tertiary system Australia’s post-2020 vision could consider a new “50:50 future of study”. That is, a 50 year curriculum of “lifelong learning” pathways beyond schooling. And a multi-platform system that can offer “50 shades of blended learning” to anyone: online or on-campus, onshore or offshore, academic or vocational.

The rub is, this would mean radically rethinking the dominant Australian model of post-secondary education: one or two rather costly and time-consuming university degrees early on, as the main portal to adult occupations and/or careers.

If good lives and good societies are to turn on lifelong learning, will “access to a university education” be seen by default as the best and fairest way to start? In a lifelong learning society, post-secondary study choices become much wider. Any “road not taken” may be just “the road not taken…yet”.

One former Bradley Review architect sees other paths of value, less widely taken:

Australia should provide an opportunity for all Australians to complete a post-secondary education program…[it] could be a skills certificate program, an apprenticeship or other trade programs, a diploma, an advanced diploma – and yes, for some, a university degree.

Bill Scales May 2020

Then there’s the abiding concern that the 1990 Dawkins reforms created a “vanilla” university sector where all mission statements and strategic goals look much the same.

The expert task force could look to offshore models for alternatives, from Canada to Korea. And bear in mind that all entail design dilemmas and trade-offs. In California in 1960, Master Plan system architect and university president Clark Kerr saw that the state’s projected enrolment growth couldn’t be funded if too many colleges “went university”.

Looking above and beyond how best to live with the crisis, it makes sense now to imagine 2020 as the year we charted our new course toward a “50:50 learning future”. For the nation to prosper, and “the great globe itself”, our temples of learning must evolve, again.

By 2030, higher learning will have undergone yet more sea-change, in ways both “rich and strange”. We will have invented further uses for Shakespeare’s “cloud-capped towers”. Perhaps at the cost of fewer “gorgeous palaces” on campus than were dreamt of this time last year.

NOTES: From Shakespeare’s The Tempest (1610)

ARIEL (sings to FERDINAND)

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange…

PROSPERO (to FERDINAND)

You do look, my son, in a moved sort, As if you were dismayed. Be cheerful, sir. Our revels now are ended. These our actors, As I foretold you, were all spirits and Are melted into air, into thin air. And like the baseless fabric of this vision, The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces, The solemn temples, the great globe itself—Yea, all which it inherit—shall dissolve, And like this insubstantial pageant faded, Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff As dreams are made on, and our little life Is rounded with a sleep…

The Tempest, Act 4

NOTES: Related analysis from Geoff Sharrock

“Organising, leading and managing 21st century universities” in Visions for Australian Tertiary Education (James, French and Kelly, Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher Education, 2017)

https://findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au/scholarlywork/1027978-making-sense-of-the-moocs-debate

https://theconversation.com/six-things-labors-review-of-tertiary-education-should-consider-93496

https://theconversation.com/from-moocs-to-harvards-will-online-go-mainstream-18093

https://theconversation.com/fee-deregulation-and-the-hazards-of-help-27521

https://theconversation.com/book-review-the-dawkins-revolution-25-years-on-19291

NOTES: University sector revenue trends

My chart breaks down only $27bn of the total $34bn universities received in 2018. It focuses on the major Commonwealth teaching and research grants on one side, and student fees and HELP loans on the other. This approach seeks to mimic Grattan Institute reporting assumptions, to show broad trends. About $1bn of “other” non-teaching, non-research funding could have been included, to lift the $11bn in “total grants” to $12bn, as seen in Education department figures. The student fee and loan figures exclude VET loans paid to dual-sector universities. In cash-flow terms, the government share of 2018 revenue is stronger than shown in this chart. HECS-HELP and FEE-HELP loans ($5.5bn) could sit with grants as “public financing” to lift this total to $16.5bn, and reduce “student fees” to $10.1bn. In accrual terms, about 1 in 5 HELP dollars won’t be repaid. So around $1bn of HELP lending could sit with grants as “public funding”, lifting this to $12bn, and reducing “student fees plus repayable HELP” to $14.6bn. The research grant figure of $3.6bn comes from the Industry department. This accounts for less than 40% of total Commonwealth R&D funding, as most of this is spent outside universities.

Bravo, Geoff. A splendid article and an insightful, provocative proposition. I hope you find many people to read these thoughts.

Having experienced the dismal insufficiency of the online learning experience offered by Australian universities (a subject upon which, given one-tenth of a chance, I will whet my incisors with relish), one of my concerns during this pandemic has been the suspicion that our universities will use this crisis to entirely decouple themselves of the costly face-to-face learning experience—if they can.

But I agree with you entirely: this situation, properly viewed, should be regarded by universities as an opportunity to engineer what is currently a very unsatisfactory mode of learning into one that it suited to the conditions of life in this century.

But that willingness and capacity to make online learning as rich an experience as face-to-face is predicated on Australian universities’ commitment to re-coupling the already exorbitant value they demand for the very little value they actually deliver—both online and offline. I’m sure I don’t have to adduce Richard Hil’s books on this subject—particularly “Selling Students Short”—as evidence of that claim.

Moreover, not just in this country, but throughout the Anglosphere, universities have completely trashed their reputations as sources of educational institutional authority, and I would hazard that the phenomenon is not unconnected with the informal, democratized ‘learning’ which takes place online. MOOCs are a good example of this.

Such a long-term project as you’re suggesting would be an excellent way for Australian universities not merely to adapt their educational models to the conditions of life in this century, but to re-couple the value proposition and rehabilitate their reputations.

My one doubt is: Do they have the will? So long as you have a self-regarding administrative commissariat at the heart of Australian universities, I would contend you don’t have the will to make such sweeping reforms to the system. Piecemeal ones along the lines we are discussing, yes, but as the administrative agenda is allied with the policy of extracting value rather than educating people so they are ‘fit for purpose’ in the 21st century, any reforms will be made cautiously and reluctantly so as not to further jeopardize their already contracted revenue streams.

Again, a wonderful article written by someone who obviously knows what he’s talking about. I wish you well in your blog, Geoff, and I look forward to reading more of your thoughts.

Thanks for reading, Dean.

As the article suggests, Australian higher education appears to have a huge adaptive task ahead, at all levels: policy, strategy, system redesign, process re-engineering, front line professional practice, etc.

While critical of the wider system flaws, I don’t think it’s fair to expect the university sector to simply self-reform under current policy and market settings. Certainly in the university I’m associated with, a lot of work has been done over the years to streamline the internal organisation. But as in big complex businesses, that kind of change is really hard to do.

In my view, the sector has displayed heroic levels of energy and commitment, to mobilise and meet an unprecedented set of demands. Over the last few months, I’ve seen leaders at all levels working under huge pressure to introduce, communicate and orchestrate complicated changes. Plus respond quickly to new and fluid circumstances week by week. Plus find ways to regulate the distress of all the communities affected…

My main aim with this piece is to open up a bit more public bandwidth on the longer-term considerations, as the steps now being taken help clarify where everyone might land later this year.

What a magnificent article dear Geoff. Thank you for lifting my flagging spirits with your well considered dissertation-coupled with beautiful prose from the immortal Bard. I must confess we are part of that pernicious breed – the private college offering both online and classroom based education from VET diplomas to professional doctorates in engineering with an all consuming passion for education. There is no doubt that online education currently and precipately presented in Australia in the main has been a disappointment. I would argue that academics have had -unfairly- to make massive changes overnight to their teaching to rather sceptical students. IMHO it is very difficult and perhaps impossible to go 100% online to a group of school leavers. But to a mature age working cadre student the picture is dramatically different. The devil is inevitably in the detail and the picture is quite nuanced…

Thanks for reading, Steve, and the kind words. I agree with the points you make- especially the “devil in the detail”. Good to hear a perspective from the private college sector, too. It’s easy for those in the university sector to overlook the wider HE sector, and see the good things that happen there.

More interesting than the revenue graph is the evolution of university expenditure priorities.

Would someone please post this?

Geoffrey – thanks for reading, and your query. I don’t have a similar graph to hand on spending. I suggest either the Grattan Institute Mapping report – a link is there in the Notes at the end of the article – or visiting Andrew Norton’s blog, which graphs a range of up to date higher education metrics on a regular basis. https://andrewnorton.net.au/